WHY DO GUNS SHOOT BETTER WITH SOME LOADS?

A friend noted that in an article he read about a new gun that the ammunition test table indicated that the match ammunition load tested printed larger groups than other loads tested. He was surprised by this and asked why.

The purpose of match ammo is to be precise, i.e., print very small groups. So, match ammunition is made with more attention to detail than ammunition used for general range practice, or often, even hunting. The manufacturer might do more sampling or testing for match ammo with the goal of making every round of the same cartridge as nearly identical as possible. That means that the tolerances from nominal specifications – that’s engineering talk for the value of a specified variable like cartridge overall length or velocity of the projectile – are as small as possible so each cartridge is as much like the next as possible.

For example, to make it simple, let’s say the manufacturer has a goal that all cartridges of a certain load exit the test barrel at a velocity that is no more or less than 15 feet per second (fps) from the nominal velocity which might be 1,500 fps. So each cartridge when fired will have a velocity out of the test barrel of no less than 1,485 fps or greater than 1,515 fps. The tolerance then is plus or minus (+/-) 15 fps. Actually, velocity variances are usually measured by standard deviation which is a statistical measure that I won’t get into here. You can research it if you want more information.

The manufacturer is trying to make each cartridge as nearly identical as possible so that when one is fired from a customer’s gun, the customer gets the same results every time. And getting the same results – like velocity and trajectory of the bullet – lead to smaller groups. But there are variables that the ammunition maker has no control over that has a huge effect on precision.

Precision is what most people refer to or look for in a gun and load combination. Precision refers to – in simple terms – how small the group on target is. It is often referred to as accuracy, but what is really meant is precision. I’ve gone over this distinction in another The What & The Why article.

Back to these other variables that the ammunition manufacturer cannot control. It’s a fact – not every shooter shoots well. The variances from shooter to shooter are huge. Some shooters manage to develop excellent skills just by practicing. Some need to get quality instruction. A good place for that instruction is Gunsite. But even after getting instruction, if that’s what you need, practice to retain that skill is necessary.

Many shooter factors have an effect on precision. And these can apply to handguns or long guns. They include things like how the gun is held, the position of the shooter, and how the shooter breathes. Some people are excellent shots and others are lousy, but the ammo manufacturer cannot control that.

Then there are variables associated with the gun used. Many of the variables mentioned below apply to long guns, but can also apply to handguns. Just like ammunition, guns are designed with nominal dimensions. Then the designers and engineers apply tolerances to those dimensions.

So, as an example, a part on a gun may have a nominal width of say .750 inch. The tolerance may be +/- .003 inches. So the part could be as small as .747 inch wide or as big as .753 inch wide. If the part is within tolerance, it would be used. And let’s say that part works in conjunction with a part that is supposed to be .500 inch long with a tolerance of +/- .003 inch. So the part could be .497 inches long or as long as .503 inches and still be good.

If the first part has a width of .747 inches and the second part a length of .497 inches, then both are within specifications, but they may not fit together as tightly as if both parts were exactly their nominal dimensions. And the parts then might work okay, but once in a while, the two parts don’t work as well together as they should, and that leads to a failure. That’s an example of what can and does sometimes happen.

And that failure could be a group with a greater than expected size or it could be a failure of the gun to function or feed a round like it is meant to. So there are really two areas that are of concern to most shooters. One is precision and the other is reliability.

Other things can happen during the manufacturing of a gun that are unexpected and not usual. Sometimes there are burrs on metal that occur for unknown reasons or because a tool used to cut a part is a bit dull. Maybe there are machine marks on metal surfaces that are not usually present. And those burrs or machine marks may be so small that they are not obvious and are not seen during normal inspections. These types of problems with the gun can affect precision or reliability.

Then there can be differences in the metal itself that cannot be seen, and they affect precision primarily. This can be especially troublesome if there are unseen characteristics or stresses in a barrel. As hard as they try, barrel manufacturers cannot predict when the metal used in one barrel is better than the metal used in another barrel made on the same day from the same batch of metal. Although some barrel manufacturers treat barrels to remove or prevent unseen stresses in the barrel metal that can affect precision, some barrels are still more precise than others.

When a bullet is fired, the barrel vibrates. This vibration can be fairly dramatic even though it cannot be seen by the naked eye. And stresses can affect that vibration. Hopefully, with a particular load, the barrel vibrates the same way every time. And, again hopefully, the bullet exits the barrel at the same place in the vibration cycle every time. If that is the case, then the barrel and load combination have a greater chance of being precise. But barrel vibration and stress are not something the ammunition manufacturer has control over. And often, despite the best efforts of the barrel manufacturer, the barrel vibrations may not be the same every time.

These variables can make a particular gun more precise with one load than with another. And the load that the gun does not like could be the match load. That’s because the combination of powder, primer, bullet, and case just doesn’t work well with that particular gun. Instead, the gun may work better with a different load that is not a match load.

As mentioned earlier, another factor in load selection is how well the gun functions with a particular load or cartridge. And this can apply to a bolt action, lever action, or any type of gun. It can be especially critical if the gun has a semi-automatic or full automatic action. If the cartridge needs to make a journey from the magazine into the gun’s breech, a gun may not work well with some cartridges and work very well with others. So this is another factor to consider in the search for a load your gun works well with.

Then there are some guns that just don’t seem to work well with any load. That’s a fact of life. Sometimes a gunsmith or the manufacturer can correct the problem, and sometimes not. But by testing different loads in the same gun, one might be found that the gun shoots well. And this fact applies to both precision and function or reliability.

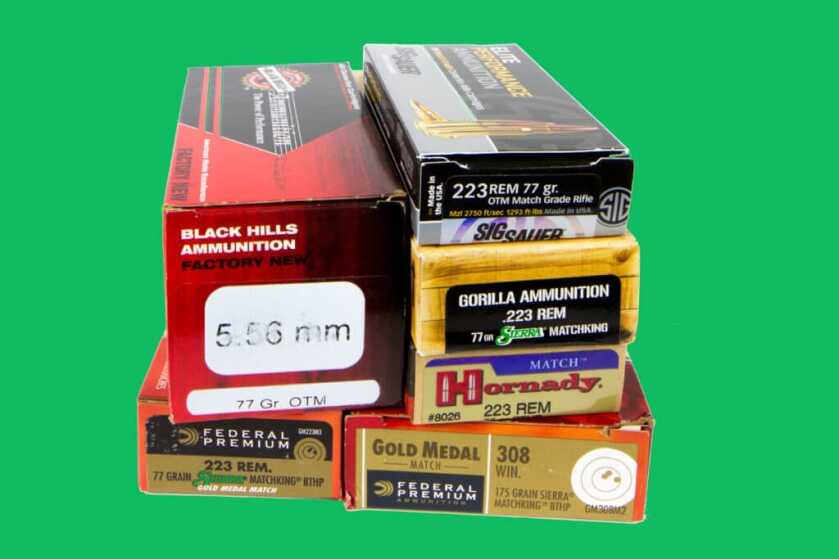

Finding the right load is a matter of trial and error. The search can go on for a very long time, or you can get lucky and find the load that works best with your gun early in the search. The only way to find the load that works best with your particular gun is to try different loads. Then try more loads. It can get expensive, so don’t buy thousands of rounds of a particular factory load without knowing that the load is going to work in your gun. It might be best to buy just a box or two and test them before buying more. And if you are hand loading, make the cartridge just a bit differently. You might try more or less powder, a different powder or primer, or a different bullet. But always follow the loading recipes published in the component manufacturer’s manual.

If you are searching for precision, you might get lucky and your gun will shoot everything into very small groups. If the gun is to be used for self-defense, precision might be acceptable and it will function with everything. I’ve tested rifles that shoot extremely small groups with every load tested. I’ve also tested rifles that are very precise with only one load – and I went through a lot of loads before I found the one that worked well. The same has happened with handguns and reliability. Some I’ve shot would digest everything well and precision was just fine for self-defense. Others would function well though with only one type of load.

Are all guns that do not digest everything or shoot tight groups with every load bad guns? No, they are not. The owner just needs to be aware of what loads those guns like, and use those loads instead of a load that the gun does not like.

So, if your gun doesn’t like to work with a particular load, don’t immediately give up. You may want to see if a gunsmith can diagnose the problem and fix it. Or maybe the manufacturer can help. Or, it may be that with the right load, you actually have a very precise or well functioning gun that you will want to keep.

And that’s the what and the why of it.

I’ve had guns that I could hit anything right out of the box. Then there were those that despite a variety of ammunition, both factory or handloads I couldn’t hit the broadside of a barn. Revolvers, pistols it didn’t matter. It almost appears that my guns have a personality of all of their own.

Ah, the old America, where we had a vast assortment of factory ammo from which to choose. Stolen elections have consequences, I guess..,