As pioneers in their covered wagons ascended the hills west of the Snake River towards the Blue Mountains, they crossed through some of the greatest mule deer habitat in the country. In the following decades, subsistence and market hunting drove deer numbers down to a scary level, and regulations were put in place to allow those populations to recover. At the same time, herds of domestic sheep began to move throughout the canyons and mountains of eastern Oregon. With them came well-armed herders with little tolerance for predators. The sheep grazed the country tightly, and behind them grew forbs, shrubs, and brush that were ideal forage for mule deer. In this perfect storm of improved habitat, decreased hunting pressure, and reduced predation, the deer numbers increased rapidly and eventually some very large bucks were taken by hunters. In 1959, the mule deer populations hit their peak and then began to slowly decrease throughout their range all across the west.

Grazing allotments began shutting sheep out of public land with policies set forth by the US Forest Service, the wilderness act, and eminent domain. One of the greatest mule deer strongholds was Hells Canyon, the deepest gorge in North America, which separates modern-day Oregon from Idaho. In 1973, Robert Cunningham from the USFS said, “The canyon has a unique recreational value that is being threatened by improvements, developments, summer homes, summer cabins, and docks.” They offered the families who had scratched out a living in the canyon two choices, $115 an acre (about a third of the appraised price) or jail. Ranchers pleaded with Congress to sell an access easement rather than be forced to sell their homesteads, but Congress decided to use eminent domain to force the sale and remove the homesteaders and their livestock from the canyon and their homes. My family was among those who were forced to sell and leave.

My grandad, Doug Tippett, continued to guide chukar and deer hunters from the river for a few more years. Deer covered the canyons and his client success rates were nearly 100% on four-point mule deer bucks. More grazing allotments were closed to sheep and cattle. Wildfires increased in frequency and severity and most of the timber in the canyon was lost. The river banks became choked with noxious weeds like poison oak and scotch thistle, and the native bunch grass gave way to invasive annual grasses. Logging ceased. Last year, more than half of the Snake River unit burned in a single fire.

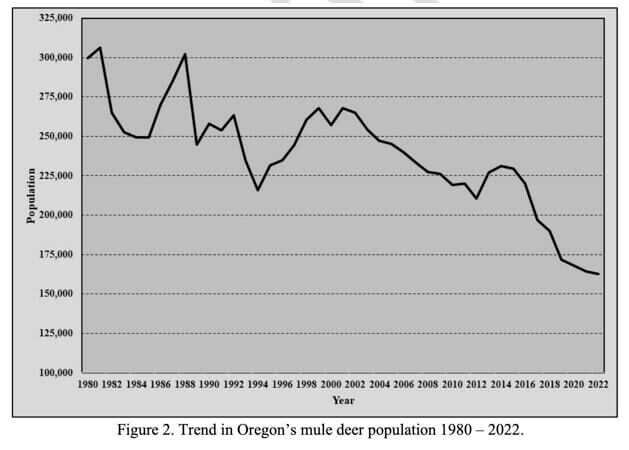

In 1981, Oregon’s Mule deer population was estimated at 306k. In 1994, Oregon’s cougar population was estimated at a sustainable 2,000-3,000. That year, ballot measure 18 passed, and hunting cougars with dogs become illegal for the public, but remained legal for government employees operating in an official capacity. The rate of cougar harvest dropped below the quota level, and those quotas have not been met since.

In 2022 Oregon’s mule deer population was estimated at 162,600 and its cougar population at over 7,000. According to Derek Broman, a cougar specialist with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, cougars tend to eat one deer-sized animal per week. Mule deer are the primary prey base for cougars in Oregon. If cougars exclusively ate mule deer, those 7,000 cats would eat 364,000 mule deer a year.

Cougar hunting is still allowed and encouraged in Oregon. A cougar tag for residents and non-residents costs $16.50. The season is open 365 days a year. You can buy two cougar tags each year. In 2021, Oregon sold over 73,000 cougar tags to the tune of 1.2 million dollars. Of those tags, around 300 were punched for a success rate of .4% which makes cougar hunting in Oregon the toughest hunt in the country.

Without dogs, there are few tactics that have proven successful. Spot and stalk, tracking, calling, and blind luck. Most of the 300 cougars killed annually are incidental, meaning the hunter wasn’t cougar hunting at the time but got the opportunity while doing something else.

Available on GunsAmerica Now

Spot and stalk is particularly challenging because cougars are typically nocturnal. During the day they tend to rest in protected areas and are therefore difficult to detect. However, some hunters are able to glass up cougars sleeping in rock formations and are able to stalk in and make the shot.

Tracking is not for the timid. After fresh snow, these lion hunters start covering miles of roads to cut a fresh track. Successful trackers like @ne.unguluteguardian use specialized transport machines to travel a loop around the area to determine if the cat is close or still on the move. Once a zone has been cordoned off, he can follow the track looking for the cougar on the other end of it. This tactic can take you for some long trips through tough country. The gold mine here is to find a trail with tracks going and coming, indicating the lion has a kill nearby and is re-visiting it. Follow him on Instagram to learn more.

Lion callers need a great deal of patience and a huge amount of luck. You will need to call for a minimum of four hours on a stand. Cougars are curious animals but they are going to come in slowly, hunting for the maker of the sound, and have incredible eyesight. You can combine calling with tracking for increased success, or you can blindly call into brushy draws or rims where you think a cat might be waiting in an ambush or sleeping for the day. Elk calf or fawn distress, rabbit distress, and even turkey calls have been known to bring in cats. Limit your movement and keep your eyes peeled.

Lastly is my preferred method, and the one I used to kill this old male this winter, which is pure luck combined with preparation. On this particular day, I was riding along to help my buddy Chad with a bird survey. We were in a portion of eastern Oregon where biologists in the 70’s and 80’s used to drive to conduct winter ground deer surveys – we had only seen one small group of deer all day. I looked across the canyon and spotted a second small herd and asked Chad whether he thought any of our cougars ever starved to death since we have so few deer left. He shook his head and said I don’t think so. About 20 seconds later I spotted this lion laying under a tree watching that same herd of deer. I had brought a bolt action Savage 223 in a KRG chassis with a Leupold mark V scope– by the time I got the scope caps off the lion was getting out of his bed and about to jump off a cut bank and out of sight. The bullet hit at the leading edge of his shoulder and he dropped instantly. I sent one more to pay the insurance. I want to be clear about something here; this wasn’t a hunt but rather an opportunity, because I had a rifle I knew how to use and a cougar tag in my pocket. Had I already seen the lion subconsciously and that’s what made me start thinking about them? Or was it actually seeing the deer that made me think about lions? Would I have seen him if I wasn’t thinking and talking about cougar/deer dynamics? I’ll never know.

Early estimates based on the distance between the skull and cementum ridge on the canine teeth put this lion at 12 years old, which means he’s killed over 500 deer and elk in his life. At the stage of mule deer decline we are currently at, every lion that gets tagged makes a difference.

Predation on mule deer tends to be compensatory in healthy populations, which means the natural reproduction of the deer keeps up with the number of individuals killed by predators. In populations already damaged by other factors such as disease, poor nutrition, decreased winter range, and poor migration corridors predation tends to be additive. That’s where Oregon’s once great mule population currently is, on the decline and doing so rapidly. Oregon’s mule deer population is down 33% just since 2017.

Start asking hunters why they hunt and you are going to hear them cite, “the challenge” quite often. Others say it’s for conservation. I’m calling you out. Put your $16.50 where your mouth is and get out here and help these deer and do some cougar hunting. You will be challenged on every level and if successful, can rest easy, knowing you made a real difference.

*** Buy and Sell on GunsAmerica! ***

Actually, compensatory mortality is mortality that does not materially add to overall number of annual deaths because other decimating factors would have operated to reduce the population in the absence of the other cause. In other words, predation does not increase the annual mortality rate over what would occur from a collection of other forces, but just replaces some other form of mortality. They would have died anyway. This is not to say that I believe cat predation has no effect on the deer population. Quite the contrary. I am saying the use of the term “compensatory mortality” is poorly understood.