Estimated reading time: 12 minutes

I recently had a delightful visit with a cousin whom I lamentably do not see very often. This was a splendid opportunity to swap tales of family history and catch up on kids and grandkids. During the course of our discussion, I discovered a most extraordinary story. An afternoon spent with Google verifies it as true.

Incipiency

By way of background, my grandmother’s maiden name was Adair. Noah Adair, Jr. was born on the 8th of August 1908, in San Bernardino, California. He was the second son of Noah Adair and Josephine Crutchfield. Noah Jr. lived in California until 1927, when he entered the US Naval Academy at Annapolis. His older brother, Crutchfield, went by “Crutch.” Crutch was born in 1901 and attended Annapolis in 1924. Crutch Adair trained as a Naval Aviator and eventually served as a test pilot.

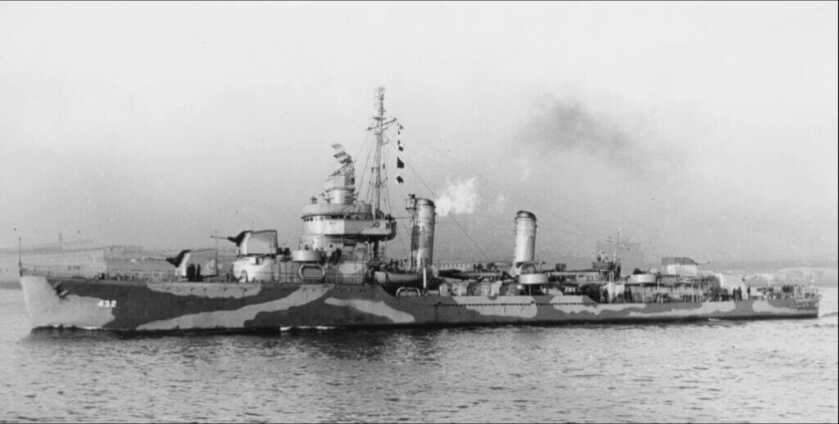

The Adair boys clearly had seafaring in their blood. Noah obviously had the ideal nautical name to boot. By October of 1941, Noah Adair was a 33-year-old Navy officer assigned to the USS Kearny, a Gleaves-class destroyer operating out of Reykjavik, Iceland.

The Come-as-You-Are War

In October of 1941, the United States was still officially neutral. The German U-boat wolfpacks were savaging British convoys shipping war materiel across the North Atlantic to support the beleaguered island nation. However, at this point in history, the Battle of the Atlantic was not yet our fight. The Kearny and three other US destroyers were moored in the Reykjavik Harbor with orders to stay out of trouble.

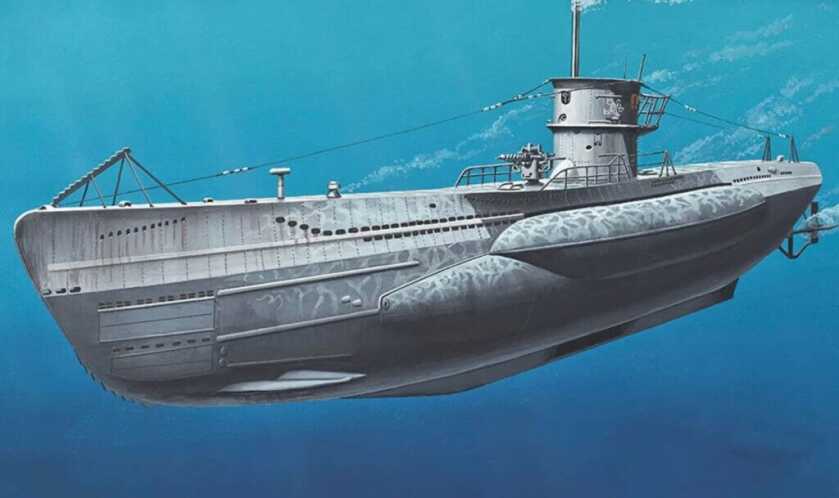

On the evening of 16 October 1941, a wolfpack of five German U-boats patrolling near Iceland launched a coordinated attack against British convoy SC-48. SC-48 consisted of some thirty-eight merchant ships arrayed in ten columns escorted by one Canadian destroyer and five corvettes. The convoy escorts were soon overwhelmed.

In desperation, the four American destroyers answered the call to support the doomed convoy. By the early morning of 17 October, whether Washington realized it or not, the US Navy was at war. The resulting combat was frenetic and pitiless.

The USS Kearny was soon positioned on the port side of the convoy, screening against further U-boat attacks. With merchant vessels burning in the background, she began launching depth charges based upon ASDIC contacts in an effort to catch one of the five marauding U-boats submerged nearby.

The Cold War Gets Very Hot

By the light of the moon, U-568, an advanced Type VIIC U-boat, launched a spread of three torpedoes at the nimble US destroyer. This was the same particular type of German submarine as was depicted in the epic war movie Das Boot. One fish passed forward of the bow, while a second was spotted behind the stern. The third, however, struck amidships and detonated.

The Gleaves-class destroyer was designed to be fast and maneuverable. As a result, it was a relatively lightly-armored warship. The standard German torpedo of the era packed 649 pounds of Trinitrotoluene (TNT) and hexanitrodiphenylamine (HND) explosive. This charge was typically adequate to cleave a merchant vessel in two. It should have been more than capable of sending an upstart American destroyer to the bottom. Only in this case it didn’t.

The resulting explosion was nonetheless still catastrophic. The Kearny had an impressive top speed of 37.4 knots (43 miles per hour) and a standard complement of 16 officers and 260 enlisted men when she was healthy. The German torpedo struck perfectly amidships on the starboard side of the vessel abreast the No. 1 fire room and detonated below the waterline. The resulting explosion killed eleven American sailors outright and wounded a further twenty-two. And the United States was not yet even at war.

Noah Adair’s crew skillfully confined the flooding to the forward fire room. In so doing, they preserved the aft engine room intact. The Kearny disengaged and headed back to Reykjavik under her own power. Eventually, the crew cleared the forward engine room and restored power there as well. As a result, the Kearny made ten knots en route to Iceland. Following temporary repairs, the Kearny struck out for Boston on Christmas Day 1941. She arrived six days later for an extensive rebuild. The U-boat attack on convoy SC-48 ultimately sank seven of the thirty-eight British merchant ships.

Desperate Times, Desperate Measures

By now, the United States was fully engaged against Hitler’s Germany. Once the Kearny was safely put to bed in Boston, Noah Adair received orders for Liverpool, England. There, he assumed command of a British Corvette now crewed by a further four US Naval officers and fifty enlisted sailors. This little escort was rechristened as an American ship and brought back across the Atlantic to help continue the fight against the wolfpacks. By 1944, Commander Adair had been awarded the Bronze Star for Valor for his command of a flotilla of these escort ships guarding trans-Atlantic convoys.

And Now for Something Completely Different…

The USS Borie was the second destroyer of that name to serve in the US Navy during WW2. The first Borie was scuttled after having been badly damaged by ramming and sinking U-405 on 31 October 1943. The second USS Borie, DD-704, was launched on 4 July 1944 and commissioned two months later on 21 September 1944. Her first skipper was Noah Adair.

Commander Adair first took his sparkly new tin can into action in support of the Marine landings at Iwo Jima. Her guns supported the initial bombardment on 24 January 1945 as well as the actual invasion the following month. Afterwards, she was ordered to join Task Force 58 for the Tokyo raids in mid-February. She then fought during the invasion of Okinawa. For a month starting 9 July, Commander Adair led the Borie as part of Task Force 38 as it raided the Japanese home islands. However, on 9 August, the Japanese hit back hard.

Details

By the summer of 1945, the once-mighty Japanese Empire was a desperate shell of its former self. However, the Japanese hive mind was institutionally incompatible with surrender. This made the Japanese armed forces incredibly dangerous. In no place was this more obvious than in the kamikaze forces deployed against attacking Allied warships.

Kamikaze means “Divine Wind” in Japanese. The name is an allusion to Makurakotoba poetry, referring to a major typhoon that dispersed the Mongol-Koryo fleets attempting to invade the Japanese islands under Kublai Khan in 1274 and 1281. In its simplest form, Japanese kamikaze pilots would strap into existing surplus or obsolete warplanes equipped with bombs and then strike out with the intention of diving their planes onto Allied warships, committing suicide in the process. Eventually, Japanese industry produced a dedicated rocket-powered suicide plane called the Yokosuka MXY-7 Ohka. While most kamikaze missions were directed at Allied ships, some of the suicide pilots were expended combating B-29 Superfortress bombers as well.

During the course of the kamikaze campaign, some 3,800 Japanese pilots took their own lives while attacking Allied troops. Around 7,000 Allied sailors were killed. The kamikaze became the scourge of the South Pacific.

On 9 August 1945, the war in Europe had been over for three months. Vast quantities of troops and equipment freed up by the German capitulation were inexorably making their way to the Pacific. The atomic bombing of Hiroshima had taken place three days before. Nagasaki would be sacrificed to the nuclear fire this very day. The war in the Pacific would be over in less than a month. However, that did not stop the Japanese from throwing everything they had at the approaching American fleet.

The Anatomy of a Pounding

On this fateful day, the Borie was operating off the coast of the Japanese island of Honshu. The Japanese launched four kamikaze planes against Commander Adair’s destroyer. Three of these suicide aircraft were downed by anti-aircraft fire or missed their target. The fourth, however, struck the small vessel’s superstructure between the mast and the 5-inch gun director. The subsequent explosion killed 48 American sailors and wounded a further 66. Of 336 sailors onboard, a third were immediately taken out of action. The attack also left the Borie’s rudder seized in place.

The Borie was critically damaged. Only via particularly skillful actions on the part of Commander Adair and his crew was the vessel kept afloat. Commander Adair was awarded the Silver Star for his actions in saving his ship during this bloody engagement. Here’s the citation-

“As Commanding Officer of the USS Borie in action against the enemy Japanese forces near the shores of the Japanese Empire on August 9, 1945, his vessel was struck by an enemy suicide plane, which caused serious fires and extensive damage. Commander Adair skillfully maneuvered the Borie while fighting and extinguishing the fires, and aggressively directed his gun batteries in fighting off subsequent enemy suicide attacks.”

READ MORE HERE: Joseph Drexel Biddle: Father of Marine Corps Close Quarters Combat

The Rest of the Story

Commander Adair survived the war. He had the distinction of serving aboard the first US destroyer to be attacked in World War 2 and commanding the last US destroyer struck by a kamikaze. He later commanded the USS Fort Marion during the amphibious assault on Inchon during the Korean War. Curiously, his brother Crutch commanded a sister ship during the same operation.

Noah retired in 1960 as a Captain. His brother Crutch left the Navy in 1954 as a Rear Admiral. Another of the Adair boys–Charles–ended up an Admiral after the war as well. I only met these guys once, and I was too young to appreciate the opportunity at the time. Finding out that your relatives were actually war heroes is like discovering hidden treasure in your attic. Thanks to the miracle of Google, the details of such stuff are only a few keystrokes distant. I can tell you from personal experience that fleshing out these old tales is a simply splendid way to kill a lazy Sunday afternoon.

*** Buy and Sell on GunsAmerica! ***

The US Merchant Marine was already in the fight in October 1941. I know our military wasn’t engaged, however the civilian crewed ships of the Merchant Marine certainly were. I know it is easy to forget us but we took a higher percentage casualties than any armed service in WW2.

This is the only article I’ve seen by Will Dabbs without MD after his name. Has he given up medicine or finally decided that MD doesn’t necessarily need to be listed in non-medical articles in gun magazines?

My great Uncle Lincoln Kyle served with the 89th Division during WW 1. A cousin, Donald Bengs, was a Marine who served in China during the inter-war years. My uncle Walter Kyle was in the 101st from Normandy to Germany. I know he received at least one Bronze Star. Uncle Wesley Kyle was in the Pacific with the 37th Infantry Division. My Dad, Evert Kyle served in Korea during that war with the 21st Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division. Two cousins served in Vietnam, Tom Miller and and Charlie Stoaks were tankers. Both survived the War, but only one survived the peace afterwords. Myself, my older sister and two brothers served, collectively, the Air National Guard, Army National Guard, active duty Army, Navy, Marine Corps and Air Force. Also, the Navy reserve, the Army Reserve and Army National Guard (different state from the other one). One of my nephews served in the active duty Army. All of us were enlisted and I don’t know of any Purple Hearts. There were three Medals of honor given to men who had the same last name as I. If there’s a family connection, my sister, the family genealogist, would know how to link them to us.

And there was one Confederate Army veteran that earned the confederate Roll of Honor. I have all 6 Marine Division histories from WW 2. In them are the names of at least two Marines that were killed in action.

I don’t know what the future will hold but I expect that when the call goes out, at least one of us will go to the sound of drums.

Great genes, brother.

Thank you Brother! On a side note, I was a Crew Chief for my 25 years in. CH-53A/D, HH-53B/C, C/HH-3E, UH-1N/H and a little time on F models, and M/HH-60G. I never got to catch a ride on any of the Army’s helos. Just Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps. One of these days I want to find a derelict Huey and restore it. Then I’d display it next to my Gun Truck War Wagon.

How do I find my grandfathers war record?

My grandmother found this stuff by interviewing surviving family members, mostly. However, that was decades ago when these great old guys were still around. I don’t think there’s any central repository of information in that regard. I’m told there is a way to get surviving personnel records from Uncle Sam, but I have no idea how to do that. Supposedly a lot of that was destroyed in a fire years ago.

If you have his name, either social security number or service number and branch of service, you can go to the National Archives. When did he serve?

I wonder just what transpired legally? If his orders were to stay put, how did he escape court martial by jumping into action? We were not at war with Germany, and he was not directly fired upon.

It’s great hearing that a relative is connected to history and has a fascinating tale. My dad was a lieutenant and combat medic in the European theater and had many stories to tell. I think I was cheap psychotherapy for him; I always wanted to hear these stories. 4 battle stars, a combat medic badge, a Purple Heart, a Bronze Star, and PTSD when he came home. His first cousin was a lieutenant in a forward observer unit for an artillery company in the Philippines and came home with a Purple Heart and a Silver Star. My uncle was a fireman in NYC and left to serve in the Navy in the Pacific and returned home to the fire dept. All these men enlisted. These were common men with uncommon valor. The Greatest Generation indeed.

Wow, just wow! Most interesting read about an intrepid family of brave warriors. Thanks for your and their service and your sharing a bit of family history.

Would you consider a further article describing how you went about searching for information on your relatives?

Thanks,

Phil- I owe much of that to my deceased grandmother. She was a compulsive amateur genealogist. When I was a kid that all seemed fairly silly to me. However, she crafted modest books on each major family line that I cherish today. Back then, in the days before the Internet, she had to do all of her research manually. I have no idea where she found her sources, though I do know she had to travel a bit to find some of them. I’d give anything to be able to spend an afternoon just talking about stuff like that with her now.

Will

Thank you once again for a great article. I always enjoy your writing.

Thank you Dr. Dabbs for another exceptional history of how our WW2 generation leaned into the maelstrom of such a global cataclysm of death and destruction.

My father was an infantry officer with the 38th Division in the Pacific Theater. Enroute to the landings at Leyte in the Philippines his troop ship was attacked by several Kamikaze suicide planes. One managed to make it through the heavy defensive fire of the ships gunners and struck the ship in the bow, penetrating several decks where it exploded. Considerable damage was inflicted with substantial losses of men and material. He wrote a compelling account of that incident and the following Kamikaze attacks as they limped into a safe bay. Although late for the landings at Leyte, Dad led his company to the end of the war throughout intense combat at the expense of four Purple Hearts and a Bronze Star.

One of his wounds was from a snipers bullet that narrowly missed his left temple, passed through the bridge of his nose and exited the right rim his helmet. He saw the muzzle flash and fired several quick shots from his Carbine at the sniper killing him. He had a Sgt. recover the Type 99 7.7mm rifle and bayonet which he brought home along with his “lucky” helmet. Shortly after being shot the intense swelling in the sinuses above and below his eyes pinched off the optic nerves which blinded him for several days. He said he took advantage of the time spent on a cot in a field hospital to do a lot of praying with ice packs on his face! When the swelling subsided and his sight returned he collected up his Carbine, strapped on his canteen and pistol belt, drew more ammo and returned to continue leading his company. Such men came hard wired through the crucible of the Great Depression to overcome such tribulations while still accomplishing the most demanding missions while immersed in the shadow of death. They certainly earned the appellation of “The Greatest Generation”.

God bless him. My dad and his cousin were also war heroes. Purple hearts, multiple battle stars, bronze and silver stars. We’ll never see men like that again.

Thank you for sharing this story. It’s good to hear the details of these events. Noah Adair was my uncle. I have a copy of a newspaper clipping of an article from the San Bernardino County Sun titled, Comdr. Adair Brings in Last Destroyer Hit, with the subtitle, S.B. Officer Blown Out of Shoes When Suicide Plane Attacks. The article states “the explosion of the suicide ship’s charge blew him out of his shoes while he stood in the pilot house of the Borie. He was not injured.”

Now that’s too cool. I suppose that means we are distant relatives, you and I. Thanks for the extra insights.

Whether on Guns America or The Armory Life, I can easily recognize — and ALWAYS appreciate — Will Dabbs’ writing. You, sir, are a storyteller par excellence!

Mike, thanks sincerely for the kind words, brother. I enjoy researching this stuff more than you like reading it. 🙂