The British Land Pattern Musket was commissioned for the British Army in 1722. Easy to make and simple to load, the British Land Pattern Musket was ideal for a globe spanning empire. It was a huge technological advance that has influenced every military musket and rifle that followed.

My musket is a Pedersoli Short Land Pattern. Pedersoli reproductions have a well-deserved reputation for accuracy and quality. The big girl is 57.75 inches long with a 41.75-inch barrel and weighs approximately 9 pounds. The barrel is .75 caliber, designed to reliably shoot a .69 caliber lead ball. This difference accommodates black powder fouling after repeated firing.

The Pedersoli has a lock with the signature of the gunsmith William Grice and the date 1762, the crown, and the alphabetical letters GR (Georgius Rex). The smoothbore barrel is made of steel, satin finish, the walnut stock is oil finish.

Considered the most advanced military firearm of her day, the Brown Bess fought the French and Indian War (known as the Seven Years’ War in Europe), counter-insurgency campaigns (like the American Revolution and the Scottish Jacobite risings), the conquest of the British global empire and on past the Napoleonic Wars, it remained in British service until 1838. It showed up with Zulu and Māori warriors as well as the Mexican Army.

The Brown Bess and her cousins were extremely popular in North America for most of United States history. It also saw action during the War of 1812 and a few even turned up in the American Civil War. Americans learn history by TV and movies and you have seen this famous girl a lot. Not only my favorite, Last of the Mohicans, but The Revenant, TURN: Washington’s Spies, The Patriot, and every pirate movie, ever.

What is so special about the Brown Bess?

Before the Brown Bess was introduced, regimental commanders selected and bought their own guns and ammunition. There was no commonality of caliber or design, so logistics were inefficient at best. The Brown Bess represented a powerful new idea – standardization.

For the first time, the pattern of the gun was officially established by the British Army. Arms manufacturers across the planet supplying the king’s forces were required to maintain a standard copy of the weapon, stored in a pattern room within the factory.

This pattern was used by gunsmiths as a template to make sure that their muskets had the same dimensions as the original. Parts were not completely interchangeable, but there were large scale production and ammunition commonality.

Design Details

The Brown Bess was a smoothbore musket. Rifles are sexier with greater range and accuracy, but they take too long to load. Muskets were cheap and simple for conscripts to operate. The British had special units of rifle troops but they were used for skirmishing and kept out of the battle line. Since muskets were not accurate, being able to reload and fire quickly was more important than aiming.

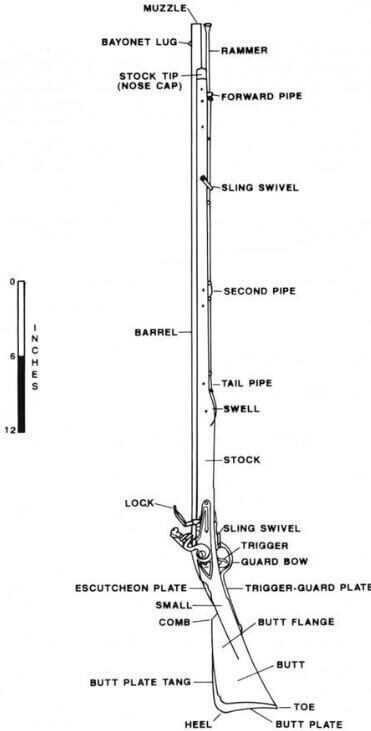

Most of the components were made from iron, the barrel, bayonet, lock work, and sling-swivels. The mainly aesthetic components such as the trigger guard, ramrod pipe, and butt plate were made from brass.

How the Flintlock Musket Works

A firearm needs a mechanism that, at the touch of a trigger, ignites gun powder. The flintlock may look primitive, but at close range, it can be just as deadly as a phaser. It was a vast improvement over its predecessor, the matchlock. To shoot a matchlock, you had to keep a piece of rope burning and lowering it into the flash pan and igniting the priming powder. This was not a Soldier-friendly system.

The matchlock gun held a burning slow match in a clamp at the end of a small curved lever known as the serpentine. The lever protruding from the bottom of the gun is connected to the serpentine. With a pull, the clamp drops down and lowers the smoldering match into the flash pan igniting the priming powder. The flash from the primer traveled through the touch hole igniting the main charge.

Gunsmiths sought a more reliable system. For thousands of years, people had been using flint to spark and start fire. First appearing in the early 1600s, flintlocks were reliable and relatively low cost. The Brown Bess lock was solidly built for rough service.

In the flintlock, a piece of shaped flint is held between the jaws of a hammer. When the trigger is pulled, the mainspring drives the flint to scrape against the frizzen, a combination striker, and pan cover. This produces a shower of sparks, which ignites the priming powder in the pan to ignite the main powder charge through a hole in the side of the breech.

A flintlock positions the hammer three ways: uncocked, half-cocked, and fully cocked. When the hammer is fully cocked, the gun is ready to fire. Pull the trigger and it moves the sear, releasing the tumbler that forces the hammer to strike. When the gun is half-cocked, it may be loaded because the trigger is locked and cannot release the tumbler. After the gun is fired, it is in the uncocked position.

In the cocked position, the frizzen is down, covering the pan. When the flint strikes the frizzen, it shaves iron to create sparks as it moves the cover away, exposing the pan that is ignited by the spark. It flashes through a small hole in the side of the barrel to ignite the powder in the barrel thereby firing the gun.

Linear Tactics

European armies used similar tactics driven by available technology. Infantry fought in dense block formations. They would approach the enemy to get within a range of 50 yards. Then each row would fire a volley at the enemy in unison. The first row would fire and then start to reload. Then, while the first row was reloading, the second row would advance and fire. Fighting in lines like this is called linear tactics.

The Brown Bess does not have sights but there is a bayonet lug where you expect a front sight to be. Infantrymen did not aim their muskets, they leveled them in the direction of the enemy. They were taught by experienced sergeants to fire low. Even if they hit the ground in front of the enemy, there was a possibility of skipping a ball into the ranks.

Training emphasized loading and firing at massed troop formations as rapidly as possible, to get as many balls flying in the direction of the enemy in the shortest time possible. In most battles, large formations of troops, spaced as close as possible leaving room to load their muskets, formed up to face each other.

The idea of lining up like this to shoot at the enemy may seem silly, but it was deadly effective. Massed fire sent a wall of musket balls flying into enemy formations. By firing in rows, each row had to time to reload while the others were firing to keep up a constant barrage on the enemy.

Most male citizens of the American Colonies were required by law to own arms and ammunition for militia duty. The Long Land Pattern was a common firearm in use by both sides in the American War of Independence.

Spirit of the Bayonet

The order to fire would be given, and soldiers would reload and advance, firing at increasingly closer ranges. When the commander decided the time was right, he would give the command to fix bayonets and charge.

Some people have described the musket as a spear that could fire a lead ball. Both the British and French used triangular socket-style bayonets. The standard British 17-inch-bladed pattern employed a simple socket with an angular channel that slipped over a lug on the top of the muzzle.

The British infantryman was rigorously drilled in the bayonet and the sight of smiling British regulars advancing with fixed bayonet was the last sight of many foes. In many battles, bayonets caused the majority of casualties. The bayonet was deadly and required no pause to reload.

The bayonet remains on the battlefield today. The most recent recorded bayonet charge was conducted in 2004 by the British Army in Iraq. It will not be the last. The Infantry knows that when all else fails, they can fix bayonets and stay in the fight. As any infantryman will tell you, the spirit of the bayonet can carry the day.

Cartridges and Cartridge Boxes

We’ve seen movies or TV where Davey Crockett pours black powder straight down the muzzle of his weapon using a powder horn. Powder horns were used by riflemen, however, soldiers used a cartridge.

The Brown Bess musket was loaded using a paper cartridge that included about 100 grains of coarse black powder and a one-ounce, .69 caliber round lead ball.

This sub-caliber ball didn’t help accuracy, but it made loading fast when speed mattered and allowed reliable loading as the barrel became fouled from multiple shoots. The paper had a twisted tail at the top to keep everything together.

In the eighteenth century, gunpowder was made more crudely than it is today, resulting in inconsistent formulation and less potency. Some records indicate that Bess cartridges took a charge of as much as 150 grains. This would be disastrous with modern powder. Soldiers of the day commented on the significant recoil such a large load had, and it was gradually reduced as gunpowder became more purified.

Cartridge boxes carrying 29 cartridges were in common use by the American Revolution. This system eliminated powder measuring in the field and made loading simple and fast for conscript soldiers. Cartridges could be made by soldiers or supporting elements in the rear.

The cartridge box was the high capacity magazine of the day. It allowed soldiers to efficiently carry multiple reloads. A soldier was expected to fire 3 to 4 shots a minute, so they went through 29 reloads pretty quickly in contact.

Ammunition

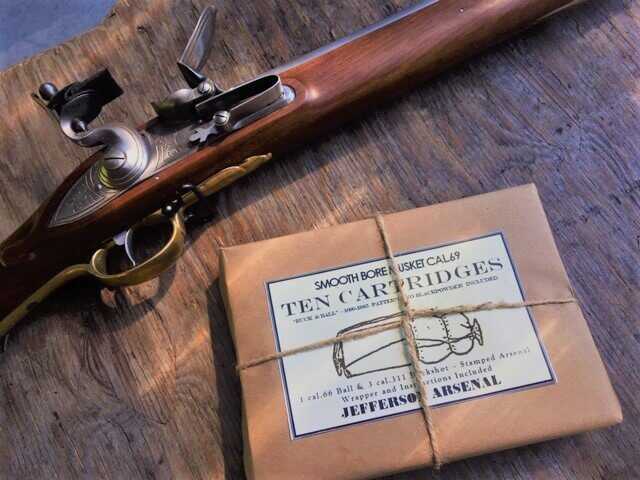

The standard British Army load was a .69 caliber lead ball. This is roughly equivalent to a 12 gauge shotgun slug (which is 0.73 caliber). My black powder buddies were full of useful hints, but I wanted to shoot in a historically correct manner. Reenactors sent me to Jon Swain of TheJeffersonArsenal.com for the real deal. Jon straightened me out on some common misperceptions. His company sells cartridge kits that are museum accurate.

That’s pretty fancy for something that you are going to set on fire and send down range, but it is still cheaper than 9mm and if you want to train like they fought, you need the real deal. I learned a lot about our ancestors shooting paper cartridges.

The British did indeed use .69 ball and Jefferson Arsenal sells those cartridges, but it turns out that Continental and militia troops used buck and ball ammunition. George Washington, possibly because of his experience in the French and Indian War, was a proponent of buck and ball ammunition.

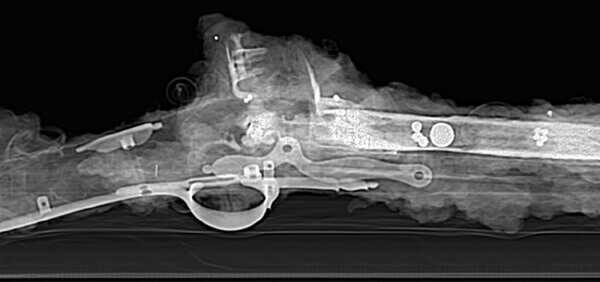

This x-ray image of a Brown Bess musket loaded with the “buck and ball” recovered in 2012 by the Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program. The ship was believed to have sunk on 31 December 1782, This vessel was likely from the final fleet to evacuate Loyalist refugees and British troops from Charleston to St. Augustine at the end of the American Revolution.

On October 6th, 1777, Washington circulated general orders that mandated, “Buckshot are to be put into all the cartridges that shall hereafter be made.” This decision came directly after the Battle of Germantown. The American predilection for buckshot continued into the War of 1812 era.

The British army never employed buck and ball as the standard ammunition, but multiple American sources report buckshot wounds from engagements with British regulars late in the war. I suspect some British corporal, angry about the casualties caused by colonial rounds, used captured ammo, and the idea caught on.

Loading and Firing

Fast firing was required of the British soldier. Accuracy was a luxury. A trained soldier might get off four shots a minute, but this soon shrank to three or even two as the weapon became fouled by burnt powder. In the defense, troops could expect to get off two volleys in the twenty-odd seconds takes their enemy to cover a hundred yards on the run.

The original drill required twelve steps to load and fire. Americans, being American, reduced this number to ten.

1) Bite off the base of the paper cartridge

2) Prime the pan, placing the cock is in the half cock, safety position

3) Close the pan

4) Place the butt on the ground. Pour the remaining powder down the barrel

5) Place the cartridge in the muzzle

6) Ram it home

7) Pack the powder

8) Cock the musket

9) Present

10) Fire

After rapid and repeated fire the gun gets very hot. Black-powder fouling builds up on the exterior of the lock and inside the barrel. It makes loading increasingly difficult and the flash hole can become blocked preventing ignition.

Meanwhile, at an undisclosed Range in the 21st Century:

So, we know the history of battles won and lost with Brown Bess and her cousins across the world for over a century. What is it like to shoot? Spoiler alert: it is fun, frightening, and final at close range.

In 1814, Colonel George Hanger wrote, “A soldier’s musket, if not exceedingly ill-bored (as many are), will strike a figure of a man at 80 yards; it may even at a hundred; but a soldier must be very unfortunate indeed who shall be wounded by a common musket at 150 yards, providing his antagonist aims at him; and as to firing at a man at 200 yards with a common musket, you may as well fire at the moon and have the same hope of hitting him. I do maintain and will prove that no man was ever killed at 200 yards, by a common musket, by the person who aimed at him.”

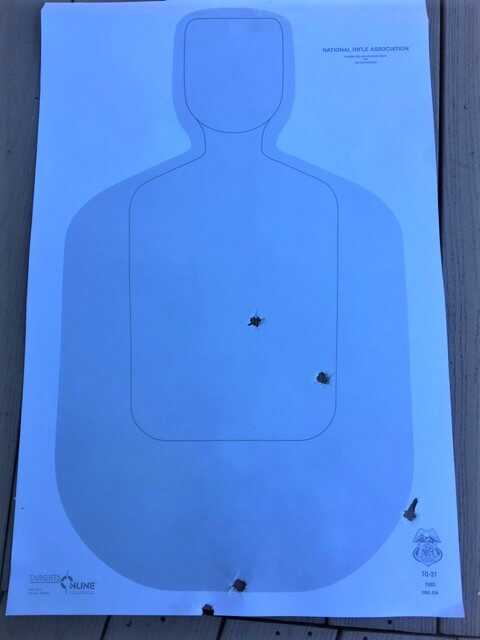

I spent several months shooting the Pedersoli Brown Bess. Taking Colonel Hanger’s comments into account, I shot full size targets at 100, 50 and 25 yards. Firing was done offhand using authentic Jefferson Arsenal paper cartridges, each containing 100 grains of FFg black powder and a .69 ball or Buck and Ball. A new flint, secured by a piece of sheet lead was clamped into the jaws of the cock.

As the gun weighs in at almost 10 pounds, recoils is similar to a 12 gauge slug. The stock is well designed with a high comb stock and wide butt plate, it’s actually quite pleasant to shoot. The biggest thing a 21st century shooter has to overcome is the half second delay.

Even though I knew better, I started using the bayonet lug as a front sight. The flash in the pan right in front of your face is impossible to ignore. I flinched and pulled a little low each shot. The potential accuracy was degraded by human factors. I was still at about 90% at 50 yards.

After 20 shots or so at 50 yards, I moved to 25 yards. At 25 I could clearly see the enemy and the holes. I started to visualize the Bess as a flame thrower. I pointed, not aimed and when the flash appeared, I imaged sending a cone of flame at the target for a full second. When the shot discharged, the barrel was on the target. I was 99% at 25 yards.

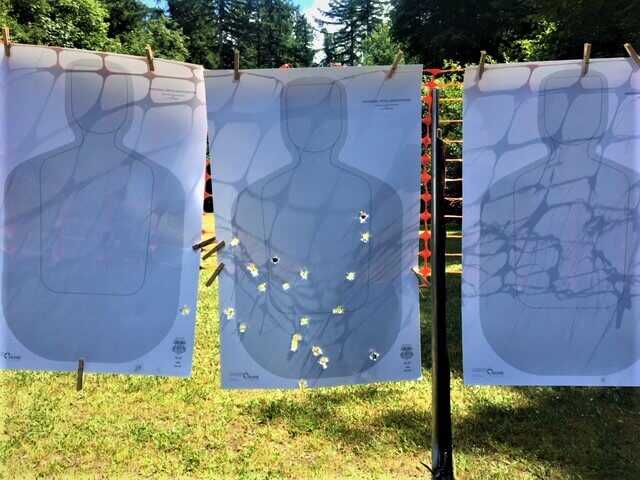

Once I knew the drill, I set up a combat course, attempting to model the shots a battle would require. Loaded 25 cartridges with .69 ball. I set up three full size targets at 50 yards and aimed at the middle target. (the other two were to see if I caught them with any misses).

I shot five rounds at 50 as fast as I could load. For the next 15 rounds, I took a step forward after each shot, as though advancing the line alternating shots with another firing line. I stopped at 25 yards and fired the remaining 5 shots as fast as I could.

I missed a couple of shots at 50, one hit the adjacent target. Once I started advancing, I got into a rhythm. I was hitting lower than I liked, but I was hitting. At 25, I could only imagine the intensity as shots were hitting and I imagined my squad mates going down around me. When would the Lieutenant let us fix bayonets and charge?

Accuracy

What I had read about, but was un-prepared for, was the delay. You pull the trigger, the hammer falls, a cloud of smoke and fire right in your face. Half a second later, when you are starting to think about misfire procedures, BOOM, a .69 caliber ball goes down range.

There is a belief that these guns are inaccurate. While that is sort of true, the shooter is the weakest part of the equation. It takes a stout human spirit to see that flash in the face and calmly await the BOOM without a flinch. Our ancestors were steadfast and stoic or they would never have hit anything.

The Brown Bess was as accurate as other muskets. The effective range was claimed to be as far as 175 yards. In typical military use, the Brown Bess was often fired at 50 yards and closer by formations to make sure shots were most effective.

Because of reloading technique, you really can’t shoot more than one round from any position other than standing. That is why you brought all of your friends with muskets and shot as fast as you could. There were men shooting back at you and you needed volume of fire and speed to overcome the enemy.

Burning black powder produces a dense grey smoke with a sulfur bad-egg stink. There is a lot of smoke and your gun gets dirty. With thousands of rounds fired at close range the dense smoke must have made command and controlled maneuver difficult. The requirement for discipline is critical. Any confusion or withdrawal could swiftly turn to route.

This was exploited by American Brigadier General Daniel Morgan at the whimsically named Battle of Cowpens in 1781. As the British attacked, Morgan placed his least experienced militia in the front and instructed them to fire two rounds and withdraw to prepared positions. The British mistook the repositioning as a rout and ran into American Regulars who poured on concentrated fire which broke the British.

Many died and the rest surrendered en mass. This was a very important American victory. The battle lasted an hour. This battle was portrayed in the movie “The Patriot”.

I like the idea of buck and ball. History shows that it was effective but I was unable to get enough buck to hit at 50 yards to evaluate the effectiveness. Up close it is devastating and a real force multiplier. A wounded guy is not going to load as fast if at all. Any guy not shooting at me is a win.

After five range days and 150 rounds, I felt like I had the equivalent of at least basic training on the Bess. Shooting this gun is a workout. The recoil and all the manipulations of the ramrod take more energy than you expect.

So what was a battle like? I don’t have the opposing forces support to do force on force, but I can shoot 25 rounds as fast as I am able, moving at the speed of fear. Having been shot at, I can tell you that the innate desire to go to ground and crawl away is powerful. It takes discipline to allow the rational mind to return fire.

In a Revolutionary War battle, you had to not only return fire, but continue standing or moving forward with your unit and loading as fast as you can until your team wins or loses. I could at least put in the rifle work and see what that was like.

Once I knew the drill, I set up a combat course, attempting to model the shots a battle would require. I set up three full-size targets at 50 yards and aimed at the middle target (the other two were to see if I caught any misses). I started with 25 Jefferson Arsenal ball paper cartridges in a makeshift cartridge box. I loaded the first round as I would carry the rifle into battle.

I shot five rounds at 50 as fast as I could load. For the next 15 rounds, I took a step forward after each shot, as though advancing the line alternating shots with another firing line. I stopped at 25 yards and fired the remaining 5 shots as fast as I could.

I missed a couple of shots at 50, one hit the adjacent target. Once I started advancing, I got into a rhythm. I was hitting lower than I liked, but I was hitting. At 25, I could only imagine the intensity as shots were hitting and I imagined my squad mates going down around me. When would the Captain let us fix bayonets and charge?

I got 19 hits on my target. Two near misses which might have hit a hand on my target and his comrade. Four round unaccounted for, I believe they went low and probably would have hit the legs.

Multiply this out and with hundreds of guys on each side and you can see that battles can’t last that long. If you stand and fight, both sides take serious losses. It is like a game of battle chicken, first side to flinch gets the bayonet in the back.

In the end, I was tired. Adrenalin would have carried me through the final bayonet assault and pursuit (if we were victorious). The alternative was being run down by enemy cavalry. These guys probably started their day with a forced march before dawn after poor and little sleep the night before on limited rations.

Terminal Ballistics

History confirms that the Brown Bess’s bullet was lethal at its full range of effective fire. According to mid-18th century tests measuring the speed of musket bullets on a ballistic pendulum, the speed of a round musket ball was about 1800 feet per second. This compares to premium 12 gauge shotgun slugs.

Given the energy of this heavy lead ball and the primitive, haphazard battlefield medical care of the period, it’s amazing that anyone survived. The wounds were contaminated by dirty clothing and soil. Before antibiotics, the infection was deadly.

Specifications

Short Land Pattern Brown Bess

CALIBER:.75

BARREL LENGTH:39 inches

OVERALL LENGTH:55 inches

WEIGHT:9 3/4 pounds

STOCK:Walnut

FINISH:Bright steel, brass furniture

BULLET weight:545 grains

Muzzle Velocity (100 grain charge):1,000 fps

Caliber.75 caliber bore, .69 Musket ball

ActionFlintlock

Cyclic rate 3 rounds per minute

Maximum effective range100 yards

The Land Pattern Musket and its derivatives were in official service for 116 years with many incremental changes in its design. Versions include the Long Land Pattern, the Short Land Pattern, the India Pattern, the New Land Pattern Musket, and the Sea Service Musket. It remained in production for 140 years, making the Brown Bess’ production one of the longest production runs for a firearm in history.

The Long Pattern is historically accurate for the French and Indian War and the American Revolution, but found the 42″ long Short Land Pattern is a more manageable length for a modern shooter. There is a reason that each improved Bess was shorter than its predecessor.

The Pedersoli reproductions are regarded by shooters as the best available to have a reputation for accuracy and quality. Many reenactors only shoot blanks. If you are a shooter and want to fire many rounds of ball at full pressure, Pedersoli’s Italian proofed steel barrel provides great peace of mind.

I learned a great deal about the Brown Bess, Pedersoli guns and the abilities of 17th century soldiers. I was surprised at some of my insights, but I came away very impressed with the British Army’s design, Pedersoli’s magnificent execution and the proven track record of 140 years of Brown Bess.

The “spirit of the bayonet” is one thing; its use in modern combat quite another. Unless your enemy is in a similarly miserable state, retreat or even surrender is a better option than a bayonet charge into even middling fire power, as the Japanese so magnificently failed to accept during WWII. Pack as much ammo as you can and keep your boots laced up for a run. Shoot the first bastard who even whispers anything about fixing bayonets, unless, of course, they happen to all be broken, and save the bayonet for it’s true purpose… opening MRE packages.

Id like to see a well researched book about the acquisition of brown bess muskets and use by the Mexican army at the seige of the Alamo.were they new weapons made for sale to Santa Anna or worn out surplus?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Xu4QQnUJRI This is very interesting. An original restoration. Sorry Mark, but either he was a lot better shot with it and or the original was a lot more accurate than the Pedersoli.

So Kurt, here is the deal with accuracy. He was using .75 caliber balls. There is no doubt that the Brown Bess can use more accurate loads for impressive accuracy. The military application required that they use .69 caliber balls to insure that they could be loaded past the fouling of black powder. A guy in his back yard in 2020 can do some very impressive accuracy with the Pedersoli Brown Bess. I was trying to reproduce the accuracy the soldiers were dealing with in the 1700’s. He also used a priming flask with a fine grained powder to reduce the delay between pulling the trigger and the bang. I plan to use my Bess during hunting season and I will use all of these tricks to get accuracy.

Excellent article! Better than reading about the latest striker fired 9mm pistol (barf). I have always been fascinated with the French and Indian War, the first world war. Alas, I was born 200 years too late. That was when Rogers Rangers were born- the forerunner of today’s Airborne Rangers, whose standing orders still apply.

As a lifelong black powder geek I’ve yet to get my very own Brown Bess or Charleville Musket. Something that I need to correct. Ah it’s what dreams are made of.

As to buck-n-ball it was also used by Irish brigades during the Civil War- um excuse me the War of Northern Agression as they say here in the south. Saw a picture I think in Dixie Guns Works Black Powder annual of a Civil War memorial with buckand ball charge. That’s how highly it was regarded. More articles like this please!

I have one, bought from Cabela’s but need bayonet and cartridges any help finding same?

In the “ammunition” section of this article there is a Jefferson Arsenal.com link in blue…you can click on it and it will take you to the JA website where you can order pre-made cartridges for several different muskets….

I can’t say enough good things about the Jefferson Arsenal. Jon Swain, the owner, is a wealth of knowledge and has a wide variety of cartridges and kits available. They make museum quality cartridges which are popular with historical reenactors of all stripes. https://www.thejeffersonarsenal.com

The guys at S&S Firearms have a nice Brown Bess bayonet.

https://www.ssfirearms.com/products.asp?cat=19

Excellent. A well done and highly detailed tutorial. Thanks.