History offers a certain clarity that is lacking for those who actually live it. For instance, I know that the First World War ended on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918 after some twenty million people perished. For the poor sots who were neck-deep in it, however, the war seemed like it would last forever.

World War One was the planet’s rude introduction to unfettered war on an industrial scale, and the blood flowed in torrents. WW1 saw the advent of submarine warfare, the widespread use of poison gas, and the cataclysmic large-scale introduction of the belt-fed machinegun to the modern battlefield. It also saw the birth of air combat.

The first violent aerial exchange between aviators took place in 1913 during the Mexican Revolution. A mere decade since the Wright Brothers’ first powered flight at Kitty Hawk, American mercenary pilots Dean Ivan Lamb and Phil Rader found themselves flying on opposite sides of the war with the opportunity to take potshots at one another with their revolvers. Alas, their hearts were not really in this enterprise, so they burned through their basic load of ammo with no effect. Both flyers returned to their respective airfields unscathed.

On August 25, 1914, a French pilot named Roland Garros flying with an observer named Lieutenant de Bernis in a Morane Parasol fired at a German airplane with small arms and injured one of the two crewmen onboard. Two weeks later a Russian pilot with a death wish named Pyotr Nesterov rammed an Austrian Albatross with his own Morane, destroying both aircraft. While Nesterov wins the prize for the first aerial victory in the history of combat aviation, he obviously didn’t live to enjoy its accolades.

The First True Air-to-Air Kill

A local legend in my little Southern town was that of a buddy’s grandfather flying Spad XIII fighters like this one created the world’s first armored aircraft using salvaged stove parts.

This was a chaotic time, and those who were there figured it out as they went along. A friend’s grandfather flew a Spad during the war as part of the Lafayette Escadrille. He slipped the cook lid from a pot-bellied stove underneath his seat, thereby creating the world’s first armored aircraft.

Much of what we take for granted today as regards aviation was revolutionary stuff indeed back in the early years of the 20th century.

On October 5, 1914, things got real in the air over Europe. Combat aircraft of this day were used predominantly for reconnaissance missions. Enemy aircrews might wave or exchange the errant obscene gesture, but that was generally the extent of their hostile actions. There was the occasional peppering with rifles or handguns, but it was all but impossible to hit one maneuvering airplane from another maneuvering airplane with small arms.

The commander of the French V.24 Escadrille, however, had an idea that would forever change the nature of warfare. He requested and received a truckload of 8mm Hotchkiss Mle 1909 machineguns through the French Army supply system. When those guns arrived at that aerodrome the whole world shifted just a little bit.

This forgotten unit commander was initially ridiculed by his peers for the very idea of mating a machinegun to a flying machine. A mere eleven years into the aviation era airplanes were still rickety deathtraps.

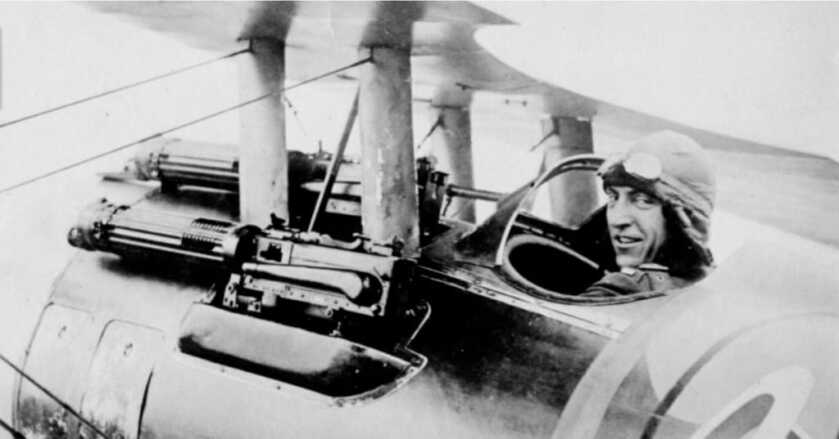

Most aircraft of this era sported a pilot and an observer, and Antony Fokker was still nearly a year away from effective interrupter gear that would allow machineguns to fire safely through the propeller arc.

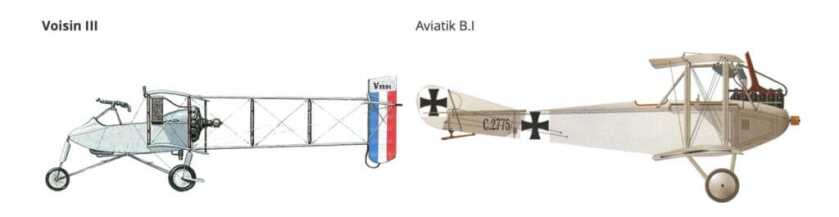

This guy’s French buddies declared that mounting a machinegun on an airplane was Jules Verne-grade folly. The V.24 Escadrille flew Voison III biplanes, however, and they sported pusher propellers. The stage was set.

The Fight

The machine in question was crewed by a French pilot named SGT Joseph Frantz along with his mechanic Corporal Louis Quenault. In addition to his observer and maintenance duties, Corporal Quenault was about to become the world’s first aerial machine gunner. The Hotchkiss gun was set on an improvised swiveling mount in the nose and fed a modest supply of ammunition. These airplanes would be considered souped-up homebuilts today and could ill afford much excess weight.

While on a patrol at 3,500 feet near the French town of Reims, Frantz encountered a German Aviatik B.1 biplane of Flieger Abteilung No. 18 busily bombing Allied troops near the village of Jonchery-sur-Vesle. The two-man crew of the Aviatik spotted the Voison as it made its approach, and the German observer Oberleutnant Fritz von Zangen was seen fumbling with a Mauser M98 rifle of his own. In response, Frantz drew his machine as close as he dared to the Aviatik and Corporal Quenault peered down the sights of his Hotchkiss machinegun.

The Weapon

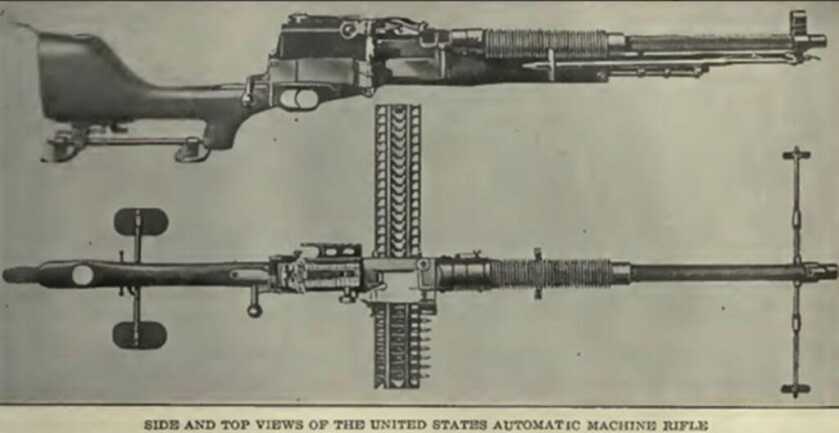

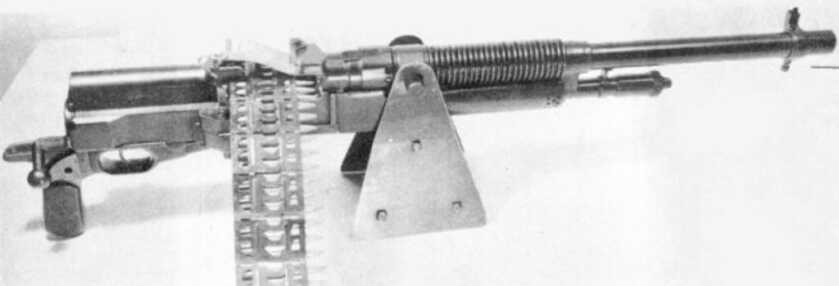

The Mle 1909 Hotchkiss fired the French 8mm Lebel cartridge and was a remarkably prescient design. The gun was alternately titled the Hotchkiss Mk I or the Hotchkiss Portative. It was also referred to as the Benet-Mercie after the American manager at Hotchkiss, Lawrence Benet, and his French assistant, Henri Mercie.

Production began at Saint-Denis near Paris. However, when the Germans threatened this area in 1914 the factory was moved to Lyon. In 1915 the British government invited the French to establish a new plant in Coventry, England. By war’s end, this facility had produced some 40,000 Mle 1909 machineguns.

The Mle 1909 was gas-operated and air-cooled. The gun was seldom issued as an Infantry weapon but saw extensive service in aircraft, tanks, and fortress mounts.

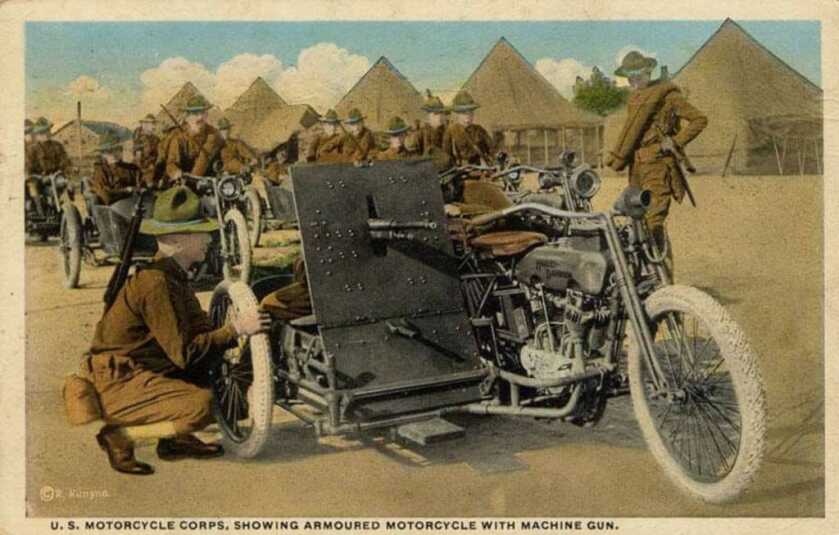

The M1909 also served with US troops during the Pancho Villa expedition in 1916 where it performed well. Some 670 copies were produced by Springfield Armory and Colt’s Manufacturing Company for use by American forces. The limited adoption of the Mle 1909 by US forces coincided with the retirement of manually-operated Gatling guns in military service.

The Mle 1909 featured a gas cylinder underneath the barrel and cycled at a sedate 500 rounds per minute. While the recoil-operated water-cooled MG08 Maxim gun weighed some 67 pounds with a full water jacket, the Mle 1909 tipped the scales at 26.5 pounds empty. These early weapons suffered broken firing pins and extractors with some regularity.

The Mle 1909 was a strip-fed gun that was serviced via 30-round feed strips manually inserted from the left into the weapon’s receiver. This design was relatively effective if properly maintained. However, the limited capacity of the strips combined with their exposed bulk conspired to restrict the gun’s practical rate of fire. They could also be deadlined by feeding the ammunition strip in upside down when rushed or terrified.

Sometime later the French introduced a metallic belt that significantly enhanced the weapon’s firepower. However, at the time of this first dogfight, this Mle 1909 packed a whopping 30 rounds onboard. This made the Corporal Quenault a very busy man.

In for the Kill

Corporal Quenault worked the cumbersome Hotchkiss gun in the nose of his Voison like his life depended upon it. He snapped off a total of 96 rounds in a series of short bursts, stitching the enemy aircraft in a variety of places before his Mle 1909 jammed. Quenault then snatched up a Lebel Mle 1886 M93 bolt-action rifle and continued the fight. Eventually, he connected with the machine’s fuel tank, and the German plane was doomed.

The pilot Sergeant Wilhelm Schlichting was struck by a bullet and killed. Trailing copious smoke the Aviatik biplane then augered into a nearby swamp. Oberleutnant von Zangen died in the crash.

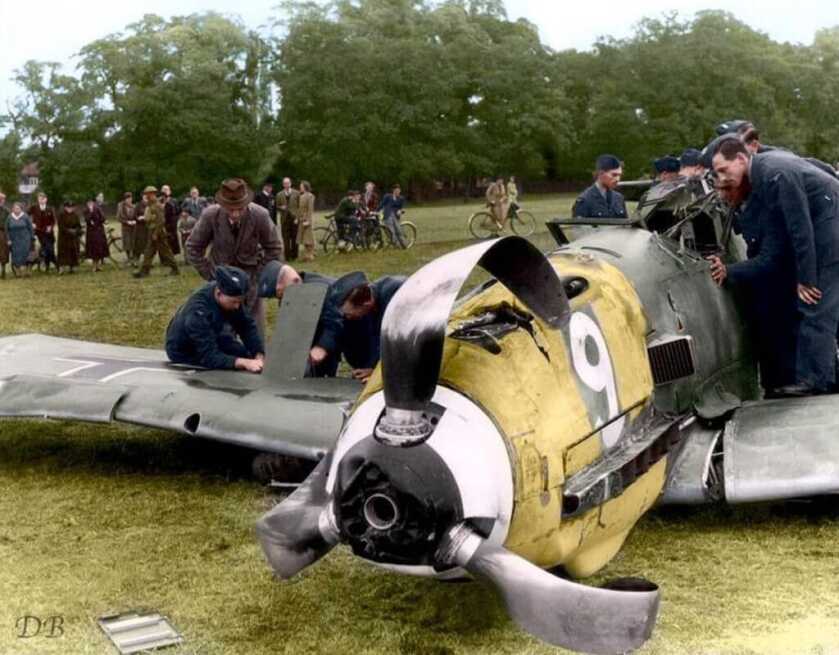

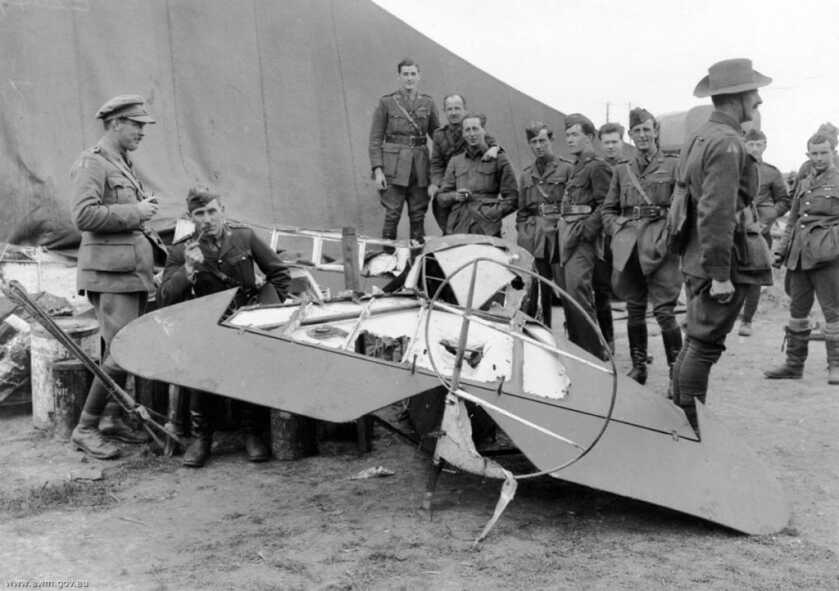

Frantz landed his machine nearby and made his way to the crash site. By the time he arrived French troops were already stripping the German plane for souvenirs. Then as now soldiers were always hungry for mementos of their time in combat. Baron von Richthofen’s red Dr1 triplane was stripped bare in short order after it was brought down in April of 1918.

The spectacle of the world’s first aerial dogfight brought the French soldiers out of their trenches en masse simply to watch. Fresh as he was off of a fight to the death with his two German counterparts, SGT Frantz was not as gleeful about these proceedings as were his ground-pounding counterparts. When Frantz was offered the German pilot’s personal effects as a war trophy he turned them down.

The Rest of the Story

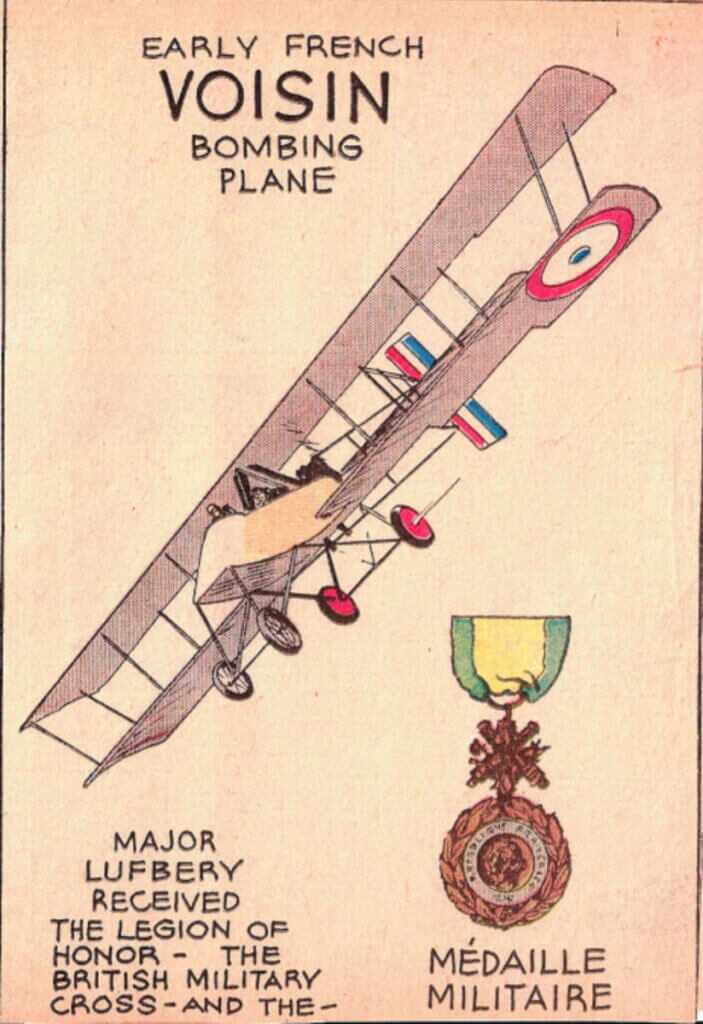

SGT Frantz was awarded the French Legion of Honour, while Corporal Quenault received the Medaille Militaire for the parts they played in revolutionizing warfare. SGT Frantz survived the war and ultimately died in Paris in 1979 at the age of 89. I found an interview with him on YouTube. However, you’ll get a lot more out of the video if you speak French, which I don’t.

By the armistice, the major warring nations had produced some 219,799 aircraft. Of those 116,250 were shot down, crashed, or damaged.

Today air superiority is a tactical necessity for any successful modern combat operation. The fact that the US Air Force and US Naval Aviation are literally unchallenged builds a foundation from which our ground forces may consistently dominate the Information Age battlefield. However, it all started with two Frenchmen in a flimsy biplane over a blood-soaked battlefield in 1914.

Great write-up! Rolland Garros’ air-to-air kills usually get the credit for first blood drawn. Now I know better! He shot down 5 aircraft in 18 days (ace). The first skirmish to result in a kill was without guns of any kind when H.D. Harvey Kelly of the 2nd Squadron R.F.C. forced down a German Taube on August 26, of 2014. The Bosche airmen escaped on foot. One pic included in your story is a D.H.2, the best pusher scout of the war and one of the best fighters before the advent of the Albatross D-1/2. The De Haviland was normally equipped with a single MG in the nose ahead of the pilot.

Everybody loves a good storyteller. Especially when the stories are obviously true…nobody can make up stuff this good! Thank you for your service, your life choices and the innate ability to tell your stories with humility and your natural flair. I feel your compassion, tempered with the reality that, as Bacon said “it is as natural to die as it is to be born”. People who are good at something, passionate about their craft and accomplishments can sense a feel of “pecking order’ when around their peers/betters. You are in the upper part of the heap. Hope you keep it up, you are appreciated. Bet you’ve read an old friend (now long gone and out of print) Timmy McLaurin. Thank you, Dr. Dabbs. Love me some Dr. Jiimmy Andrews, too.

Much enjoyed the write up, thank you

Great historical research…thank you!

Thank you, for an interesting and informative article. I enjoyed reading it!

A fun and informative read. As a companion to the article, I’d recommend watching the spectacular 1927 silent movie “Wings”, directed by William Wellman. Wellman was the real deal. He was a pilot in the Lafayette Escadrille. The filming of the aerial battles is stunning to the least.

Wings is also the very first Oscar winner for Best Picture.

Give it a watch!

The Germans, in WWI at least, had no “moral failings”, or at least any that were any different from their enemies. There were many Americans who thought we (the US) joined the wrong side in that war, that it would have been better to leave it stalemated.

While it is amazing to think of going to war in one of these contraptions, I still have difficulty getting my mind around men standing in formation in the open and shooting at each other, as in revolutionary war days.

I would tend to agree with many of those early opinions of the war; but Americans just couldn’t abandon the French, who gallantly stood by the early US during our early development. I think we can admit we’ve paid them back three times over now!

I agree.

I love Doc Dabbs writing, but that was a totally unnecessary jab. The Germans had no more moral failings than any other nation, including the US. It wasn’t that many years earlier that a corrupt US government started and waged an unjust colonial war against Spain. Plenty of “moral failings” to go around.