We live in the age of the high capacity semi-automatic pistol, but thirty or so years ago, the revolver was the predominant self-defense handgun used by sworn–i.e., police–and non-sworn civilians for duty and protection. Even though semi-automatic pistols are most often carried these days, a large number of people in both camps still carry a revolver, some as their primary defensive sidearm or as a backup piece. But sadly, competency in the manipulation of wheel guns for self-defense is, if not a lost art, a skill that most revolver carriers lack. And not knowing how to run a revolver can get you or a loved one killed or injured.

The object here is to reveal some of the methods to run a double action (DA) revolver with a swing-out cylinder, although there may be some carryover in techniques to single action, top break, and gate loading revolvers. These methods are not the only way to manipulate a DA revolver but are one way.

Caution: Don’t think you can learn to competently run a revolver–or any gun for that matter–by reading a book or an article or watching a video. There is no substitute for in-person instruction by a competent instructor. But the first step in learning is to realize that there are things you don’t know and that you need to know. Perhaps that’s the real value here.

These techniques are taught by some of the best gunfighting schools in the world, like Gunsite Academy located near Prescott, Arizona. Although not all firearms instructors know how to run a revolver, the instructors at Gunsite do–even single action revolvers for that matter. So if you want to rely on a revolver as a life-saving tool, find a good instructor, pay the money, spend the time and get the training.

I recently attended an event at Gunsite where techniques for running a DA revolver for self-defense were taught. I used ammunition from Aguila and Black Hills along with a Smith & Wesson 686 revolver chambered in .357 Magnum and customized by ROBAR. It was carried in a Blade-Tech Classic OWB Holster. All equipment and ammunition performed flawlessly.

The Smith & Wesson 686 is a stainless steel six-shot revolver chambered in .357 Magnum which is highly regarded as one of the best fight stopping handgun rounds. The 686 is a good gun out of the box but can be improved. (Doug Larson photo)

An important characteristic of DA revolvers is that stroking through the trigger pull rotates the cylinder to put an unfired round in line with the barrel and at the same time retracts the hammer. At the end of the trigger stroke, the hammer is released to ignite the round. Some DA revolvers operate only in the manner just described and these are often referred to as DAO or double action only revolvers. But a DA revolver also allows the hammer to be cocked by pulling back on the hammer spur until the hammer is fully cocked and the cylinder is advanced. With the hammer locked back, the trigger can then be pulled allowing the hammer to fall. DAO revolvers do not have this feature.

Cocking the hammer by thumbing it back on a DA revolver in a self-defense situation is rare. First, it takes longer to fire a round and second, once the hammer is cocked, the amount of trigger pressure required to fire the gun is very little which makes an unintentional discharge more likely. It might be appropriate if a very precise shot is needed and there is time to execute it, but the shooter must decide that for himself after careful consideration of the individual circumstances.

Although the longer and heavier trigger pull on a DA revolver may be more difficult to master than the pull on a single action or striker fired gun, and the revolver usually carries fewer rounds, there are other characteristics that make a revolver a good choice for some people. Modern DA revolvers have no safety levers, so there is no chance of forgetting to disengage a safety under stress. And some people have difficulty retracting the slide on a semi-automatic, but with a revolver, that problem is eliminated.

A common complaint is the revolver’s heavy double action trigger pull. But the pull can be smoothed and lightened which is what ROBAR did on the S&W 686. In addition to smoothing the stroke, the pull weight was reduced from 13 to 11 pounds which makes it easier to maintain proper aim while pressing the trigger. It also helps to increase the speed of follow-up shots.

ROBAR also applied NP3 which is a nickel plating embedded with PTFE–the same stuff that’s in Teflon–making the surface very hard and slick. NP3 is used on space hardware, so it’s pretty high tech stuff. Internal parts were also coated with NP3 making an already good trigger job that much smoother. Not only does the NP3 look great with its matte nickel finish, but it is also easier to clean.

S&W 686 After ROBAR. The S&W 686 used at Gunsite was customized by ROBAR. The gun’s exterior and internal parts were finished with NP3, which besides looking great, hardens the surface and adds lubricity. A trigger job improved the already good trigger pull and reduced the pull weight making the gun easier to shoot. (Doug Larson photo)

Lastly, the factory ramp front sight with the orange insert was replaced with a far superior brass bead making it easier to obtain a good sight picture. That is especially obvious in bright sunlight where stainless steel glares. All of these custom improvements make an already effective DA revolver much better for self-defense.

Front Sight. ROBAR removed the ramp front sight and replaced it with a black front blade featuring a brass bead. This made sight acquisition faster, especially in bright sunlight where the glare of stainless steel can hamper obtaining a good sight picture. (Doug Larson photo)

Although a shooter should practice firing the revolver one handed with either hand, it is more effective to use a two hand hold. But that hold is a little different compared to a semi-auto. First, grip as high on the backstrap as possible to help control muzzle rise. And keep your fingers well behind the gap between the cylinder and the rear of the barrel. High-velocity hot gas is emitted from this gap with every round, and it can injure or even sever a finger.

One grip technique is to lock the offhand thumb over the firing hand thumb. Another is to place the offhand thumb behind the backstrap on top of the firing hand. Still, another is to place the offhand thumb below the firing hand thumb along the frame. Just don’t get near the cylinder gap. You will make that mistake only once before you learn the lesson.

Two hand hold. This is one method of gripping a DA revolver. Notice the off-hand thumb wraps over the firing hand thumb and no fingers are near the cylinder gap. (Doug Larson photo)

To load, open the cylinder, cradle the gun in one hand and then drop a cartridge in each chamber. Carefully look at the back of the cylinder to make sure each charge hole is filled. Don’t laugh, sometimes we look but don’t see, so make a conscious effort to examine each hole before locking the cylinder into the frame. And don’t flick the cylinder shut while holding the gun by the grip and rotating the hand. Some Hollywood director thought it looked cool to do that, but it can damage the crane. So push the cylinder closed with the offhand using your thumb or fingers. Then it’s a good idea to slightly retract the hammer so that the cylinder stop is disengaged and the cylinder can be rotated freely. Rotate the cylinder 360 degrees to make sure nothing impedes the movement, then carefully lower the hammer and continue rotating the cylinder until it locks. Always point the gun in a safe direction in case there is an unintentional discharge.

Making sure the cylinder rotates freely is important because you don’t want to find out it won’t in the middle of a fight. Rotating it may cause a drag line around the cylinder, but you can probably live with that because you are carrying a life-saving tool, not a showpiece. Right?

The revolver usually has five or six charge holes or chambers in the cylinder, although some revolvers have more. Regardless of the number, the capacity is usually less than a modern double stack semi-automatic, and loading is slower, so managing ammunition is critical. If possible, keep track of the rounds fired. That’s pretty hard to do under the stress of a deadly force encounter, so if you fire a few rounds, there is a lull in the action and you can safely do so, reload.

And when the gunfight is over and the threat is gone, reload so that if another threat comes along, you have a fully loaded self-defense tool. To do so, hold the gun with the muzzle slightly down, open the cylinder and slowly push the ejector rod partially to the rear. Then let it go back into place. Hopefully, the fired empty cartridge cases will protrude from the cylinder while unfired rounds fall back into place. Pick the empties out and let them fall. They are no longer useful. Using a Tuff Products QuickStrip (www.tuffproducts.com) or loose rounds from a belt carrier or wherever you carry them, refill the empty charge holes and close the cylinder. When done, scan to make sure there are no threats then holster the gun. That’s an administrative reload.

Loose round administrative reload. Gunsite instructor and rangemaster Lew Gosnell demonstrates an administrative loading procedure where the cylinder chambers or charge holes are loaded one or two at a time with loose rounds. (Doug Larson photo)

Some revolver cylinders rotate clockwise and others counter clockwise when viewed from the rear. Know the direction of yours so if you are unable to fully load the revolver because someone is shooting at you, you can close the cylinder so a live round rotates into position when you pull the trigger. If you make a mistake and the hammer falls on a spent round or an empty chamber, keep pulling the trigger until the gun fires. It’s much faster to keep the trigger going than to stop, open the cylinder and realign the cartridges.

In fact, it’s a good idea to practice loading one round at a time, firing it, and then loading another round. If your revolver runs out of ammunition in the middle of a fight and you cannot quickly load all chambers, you may be able to defend yourself with this technique.

The following procedures are for a person firing the gun with his or her right hand. Left handed shooters will have to modify these techniques to make them work, but the principles are the same.

If you are in a fight and have to reload, move fast and try to get to cover. Sometimes it may be smarter to reload all charge holes at the same time even if you have a few live rounds still in the cylinder. Each gunfight is different, so it’s your decision and no one except you can make it.

The first step is to open the cylinder by pushing the cylinder latch with the thumb of the firing hand. Some models push forward, others in and others to the rear. Make sure you know which way to push yours.

Opening with firing hand. Not everyone can do this, but here the shooter presses the cylinder release with his thumb while at the same time pushing the cylinder open with the index finger of the same hand. Once the cylinder is open, loading is accomplished with the left hand. (Doug Larson photo)

Now, if your hand is big enough, you may be able to push the cylinder open with the fingers of your firing hand. Not everyone can do this. For those who can’t, while the latch is disengaged, cradle the gun in the left hand with the trigger guard in your palm and push the cylinder open with the two middle fingers of the same hand. Continue to hold the gun in this manner with the two middle fingers touching the cylinder through the window created in the frame and the thumb of the left hand touching the cylinder. This prevents the cylinder from closing or rotating.

Ejection with right hand. Many shooters must transfer the revolver to the left hand in order to open the cylinder. The thumb and two middle fingers of the left hand hold the cylinder so it will not rotate and the palm of the right hand is used to sharply slap the ejector rod to remove spent cases from the cylinder. (Doug Larson photo)

Then point the muzzle up and with the palm of the right hand, quickly and forcefully hit the ejector rod pushing it all the way in and then letting it spring back into place. If luck is with you, this will force empties and live rounds out of the cylinder. Let them fall away. Some say to hit the ejector rod with the left thumb, but that may not provide enough force or speed to get all the empties out of the cylinder. Do it however you want, just make sure the way you choose works.

Ejection with thumb. Another way to operate the ejector rod is to use the thumb of the left hand. If you use this method, be sure that enough force is applied so that no spent cases remain stuck in the cylinder. (Doug Larson photo)

Next, rotate the gun so the muzzle is pointing down. Using your free hand, drop fresh rounds into the cylinder. Speed loaders like those made by Safariland or HKS and moon clips are the fastest, but you can use loose rounds or a QuickStrip. When the speed loader or QuickStrip is empty, let it fall to the ground.

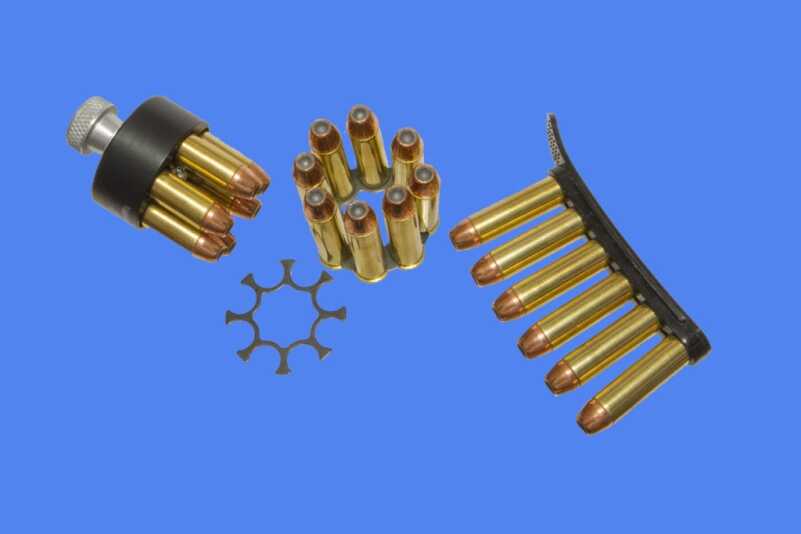

Loaders. Loose rounds are sometimes used to load the revolver, but most people find that devices like the speed loader (left), moon clips (center) or QuickStrips make handling cartridges easier and loading faster. (Doug Larson photo)

Next, forcefully close the cylinder with the thumb of the left hand while applying some rotational force to the cylinder so that it locks in place. Get back on the sights and determine if another round needs to be fired.

Where do you carry your reloads? That’s up to each person, but moon clips and speed loaders are a little bulky while loose rounds and QuickStrips are less so. Pockets work but are not the best. Simply Rugged Holsters makes pouches that can be worn on the belt for all the options. Generally, reloads should be accessible with either hand, so this means wearing them somewhere near the front of the body.

And if you are using moon clips or speed loaders, make sure they work with your gun before you need them for real. Sometimes grips interfere with their use, but replacement grips that work may be available.

Loading moon clip. An advantage of moon clips is that all rounds are held together so that the cylinder can be completely filled at once. All rounds, both spent and live though, are ejected at the same time when the ejector rod is pressed, so reloading only spent rounds is not possible. (Doug Larson photo)

If you think that revolvers are foolproof and never malfunction, you are mistaken. Sometimes, especially with powerful ammunition and lightweight revolvers, bullets can actually be pulled slightly forward in the cartridge case by recoil and protrude far enough so that they contact the frame and keep the cylinder from rotating. That may also prevent the cylinder from opening and cannot be fixed fast.

Case beneath ejector. If a spent case gets stuck beneath the ejector star in the middle of a gunfight, it means real trouble because it is difficult to clear quickly and a tool will probably be needed. Revolvers can and do malfunction. (Doug Larson photo)

Sometimes a primer may not be fully seated which also stops the cylinder from rotating. Dirt or grit can get into the internal mechanism and bind everything. And if the trigger is not allowed to fully return forward after a round is fired, sometimes the internals can bind and a stoppage occurs. If the ejector is not forcefully and quickly struck and empties don’t fall cleanly away, a cartridge rim may get caught under the ejector star making the gun useless until the cartridge is removed. And if dirt or unburned particles of powder get between the back of the cylinder and the ejector star, the cylinder may not close or rotate. So although revolvers are not subject to single round feeding or ejection problems, other things can go wrong. But using quality ammunition, manipulating the revolver correctly and keeping it cleaned and lubed will help to prevent these malfunctions.

Even though the revolver design is old, revolvers are still effective self-defense firearms and are carried by many people. But knowing how to run them and then practicing is important.

*******************

A former Contributing and Field Editor for Guns & Ammo magazine, Doug Larson’s articles have appeared in many top firearm publications. He has completed hundreds of hours of firearm and self-defense training provided by some of the finest world class gun fighting instructors and schools. He has experience with handguns, rifles, shotguns, submachine guns, machine guns, and other crew served weapons.

I, too, carried S&W and Ruger revolvers for a living for years, and never felt undergunned by them. But all these articles ignore the one factor that tilts in favor of the modern polymer pistol: weight.

The L-frame revolver the author writes about here weighs over 40 ounces. The smaller K-frames that I carried weigh about 35 ounces, and the N-frame the Gunsite instructor is using weighs around 45 ounces. A modern polymer pistol by Glock or S&W weighs from 26 to around 35 ounces.

When I was a brand-new agent in my 20s back in 19 (mumble, mumble), weight was not an issue. But 30 years of LE work has left me with chronic pain as a result of several serious IODs, six on-duty car crashes, and general wear and tear from walking, running, fighting, and falling with, among other things, a two-pound pistol, extra ammo, handcuffs, baton, etc., on my belt. I was glad that in the last few years of my career I could carry a lighter polymer pistol.

The revolver is an effective tool. I love the old Model 66 and I would not, in theory, feel undergunned with one. But the modern pistol weighs half a pound less, carries twice or more the number of rounds, is easier to reload, and easier to carry concealed.

I’m certain the Author has a lot of experience, but the claim of a brass bead being “far superior” to an orange insert I find arrogant.

I hunt with a revolver, and have since ’78. I have found the orange ramp and especially the glow ones to be better all around for me, in any situation.

The brass bead is old hat, and overrated. Especially true in low light, moving target conditions.

For me. YMMV.

Alan,

Obviously you don’t know a lot about sites. Don’t criticize the writer when you don’t understand different sites. Brass is easier to pick up in bright light as stated in the article. This article was talking about self defense not hunting. You want to be able to pick up front site as fast as possible when your life is at stake. Maybe read articles twice before commenting.

When I started in law enforcement in 1977, we carried .38/.357 revolvers. My first was a a S&W Model 28 4″ barrel “Highway Patrolman”, which was a .357 on a .44 frame. Great gun. I replaced it a few years later with a S&W Model 19. By then, we had been limited to .38 +P in the gun, but could carry .357 for reloads. I retired 4 years ago, having carried a number of revolvers, then .45 autos, followed by 9mm hammer fired Sig P226s and striker fired Glock 17/19/26. While I alternate between a 9mm or .45 auto and a .38/.357 compact revolver (S&W, of course), I don’t feel under-gunned with the revolvers

The proper way to close a cylinder is with a thumb on the crane. This permits the cylinder to index properly without resistance to turning, as might occur if you close it by pushing on the cylinder. This method also dispenses with the need to partially cock the hammer, because the cylinder is turning freely so the indexing pawl does not have to be retracted.

This is an ammunition problem, and can happen with any firearm. I’ve seen it happen several times in semi-auto handguns. (Of course, that’s almost all I ever see people shooting. My point is that the squib is no unique to the revolver.)

I’ve always carried a s/w 3in. 357. If you can’t stop anyone with six rounds… then you have no business carrying a handgun”

I believe the instructor is demonstrating a Taurus revolver, although I’m not familiar enough to name the model.

The gun is either a S&W Model 21 .44 Special or a Model 22 .445 ACP/AR. Excellent revolver in the old style S&W design. I have a Model 22 and am currently looking for a Model 21. I’m very fond of the old fixed sight, tapered barrel Smiths.

I stand corrected. It most certainly is an S&W. Thanks!

My experience with handguns has been for plinking and target shooting, so my thoughts may be a bit different than those of the author. My reason for preferring a revolver to an autoloader is that they do not throw your brass away. The author even suggested dumping live rounds, which could get one in legal trouble if not retrieved prior to leaving the site. The only autoloader that I would consider is a 1911 with a .22 RF LR adapter on top, because you cannot reuse the brass. Other autoloaders do not have the intuitive safety features of the 1911.

Interesting and worth a look. Since I rarely shoot .357 rounds (my seventy-something wrists) I use .38 Spl rounds in my 686-7. They shoot well enough for me, and I really don’t need all that extra power. My general use in this caliber is a nearly century-old Model 10 with a four-inch barrel. Hollowpoint .38’s do the job well enough for me. The Ashley upgrades look nice, but again if the pistol needs upgrading, why buy it to begin with?

Nice pistol but I have a few already – and all but one have NO built-in locks. That always bothers me since you can lock a revolver with a decently thick padlock shackle and not have extra keys to deal with (same key as locks several other things at my place).

Carried a 629 twenty years patrolling the hood. Would carry the same again.

Can you tell us what revolver the instructor was using in most of your photos? I know it’s a S&W but can’t figure out the model or caliber.

It’s either a S&W Model 21 in .44 Special or a Model 22 in .45 ACP/AR.

Give yourself an edge! If you can carry a medium framed 4″ revolver get the 7 shot 686 Plus or the 7shot 9mm 986. If large frame is OK go for a 627 Pro!

Great article. Being a law enforcement officer in the early 80’s I used a 686 revolver and competed with it also. Still have a 686 and shoot it often.

Hallo doug. All my s&w revolvers are tuned by Dr. Nelson Ford at the Gun Smith in Phoenix az.

Other wise a competent article.

Nobody doubts beasties like the 686 are good “fight stoppers” –mere sight of that iconic profile may well keep one from ever starting. However medium-frame & larger wheel guns are not exactly the ideal concealed carry pieces for civilians. Just looking at online stores indicates the majority of defensive wheel guns sold today are little snubbies chambered in .38 Special/+P. Some handle .357 Magnums but with a 2″ barrel it may not add a whole lot to anything but the light show.

I read your article with interest, as I’ve recently changed my CCW from a striker fired semi-auto to a revolver. Here are a couple of observations: First, you chose what I would consider a large revolver. There are many smaller 5 and 6 shot guns that are easier to carry. Second, i’ve read several articles and books that advise against modifying your carry gun. Furthermore, after a self defense encounter, it’s wise to put your gun down in plain sight and wait for the arrival of Law Enforcement. An arriving officer does not want a loaded gun involved let alone one that’s been reholetered.

Back when I started in police work we were issued a S&W 38spl revolver with 18 rounds of ammo, six in the revolver and 12 rounds in a dump pouch. Off duty I carried a 1911and/or my revolver. All these years later and I still qualify every year, (LOSA) with my 1911 and a 357 revolver.

The most common problem I have encountered with my revolvers is a “squib” round- projectile enters barrel but does not leave- making any follow up shot dangerous until the projectile is cleared from barrel. Generally the recoil is quite diminished with a squib round and I need to be sensitive to this particularly when practicing double taps. Still carry my S&W 360PD most often and use the best ammunition I can purchase.