Scroll through any forum for ammunition reloaders, and you’ll often see the same advice for newbies: start small. Don’t buy a progressive press right off the bat. Start with a single-stage. Don’t get a fancy powder thrower before you’ve worked with a balance scale. Don’t buy an expensive die set until you know how to use a basic set from Lee or Hornady.

This is good advice, generally speaking. If you aren’t sure whether you’ll have the time or inclination to spend hours at the reloading bench, you shouldn’t drop $1,000 for a setup you might only use occasionally. Still, if you buy basic now and then decide to upgrade later, your final bill will be even higher.

That’s why I was drawn to the Competition die set from RCBS. It fills a nice middle space between a $289 Redding set and a standard $45 kit from one of the other big manufacturers. At $100-$125 (depending on where you buy), this two-die package includes some of the features found on more expensive products without the associated costs.

Along with the seating and sizing dies, the kit comes with an extended shell holder and an Allan wrench for locking the dies in place.

The RCBS kit includes a full-length resizer die and a bullet seating die. Both dies are constructed from case-hardened steel and are precision-drilled, reamed, polished and hand-inspected twice before leaving the factory.

The full-length sizer die takes cases to SAAMI minimums and features a raised expander ball, which (according to RCBS) provides extra leverage for easier neck expansion. It also includes vents to prevent case damage from trapped air and excessive lubricants.

The sizer die works fine, but I didn’t feel much difference compared to my experience with other products. I reload .308 WIN (because I’m a grumpy old man who doesn’t think 6.5 Creedmoor will catch on), and while some cases took more elbow grease than others, I didn’t experience any issues. If you prefer a neck sizer die, you can find RCBS models for about $35.

The bullet seating die represents the real value in this kit. It doesn’t crimp cases, so if you’re planning to reload for a semi-auto or have other reasons to crimp, you’ll have to purchase a crimping die separately. (Also check out Tom McHale’s excellent explanation of crimping here.)

Two features separate this seating die from other options.

First, the micrometer allows users to adjust seating depth in .001” increments and use the same setting for the next batch of rounds. I seat my bullets to .02” off the lands of my rifle, and it’s nice to be able to adjust each bullet precisely to maintain consistent overall cartridge lengths. I can record the proper depth on the micrometer for each bullet and dial down to that number each time I want to seat those bullets.

The micrometer itself is quite consistent. Slight variations in bullet ogive (the curve of the bullet) will generate slightly different overall cartridge lengths, so if you’re trying to be super precise, it’s best to dial the micrometer up for each new bullet. But on any particular cartridge, the micrometer adjustments corresponded perfectly to the new seating depth. To test this, I took a bullet and dialed the micrometer down in .005” increments and then in .001” increments. I measured the overall case length each time using a bullet comparator, and the micrometer was always spot-on.

The micrometer works great, but the best feature of this die has to be the bullet seating window and alignment sleeve. As Tom McHale explains in more detail here, bullet runout (also sometimes called “concentricity,” though this is technically incorrect) describes how “straight” a bullet seats in a case. Seating a bullet crooked will result in less consistent points of impact and, consequently, larger groups. Standard seating dies require the user to hold the bullet straight until the bullet and the case enter the mouth of the die. While I’ve seen reloaders produce excellent ammunition with these kinds of dies, they do add another variable into the bullet seating process.

The alignment sleeve on the RCBS Competition Die minimizes the risk of crooked bullets by aligning the bullet with the case mouth before seating. Users simply run the case into the die, place a bullet inside the sleeve via the loading window, and seat the bullet.

I, unfortunately, do not own a bullet runout gauge, which would be the best way to compare runout between different seating dies. But proper equipment has never stood in my way before, and I’m not about to let it now.

I loaded ten rounds with the RCBS dies and ten rounds with a standard set from another manufacturer. I kept everything else the same – bullet, brass, powder, primer, and overall length.

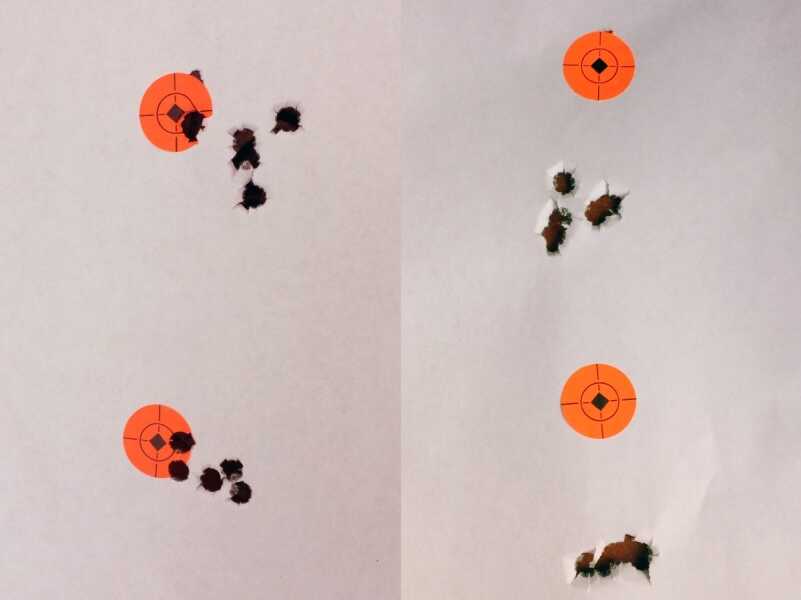

Left targets were seated with a standard die and produced groups 1.21″ and 1.15″. Right targets were seated with the RCBS die and produced groups 0.725″ and 0.891″.

Admittedly, this is a small sample size. Other variables might also explain this difference in accuracy (barrel heat, for example). But considering I shot these groups on the same day with the same gun, and I made sure that each cartridge was virtually identical, bullet runout seems like a plausible explanation. I’d have to conduct more testing to verify my hypothesis, but I think even these initial results are telling.

Bottom line? If you’re looking to squeeze every last ounce of accuracy out of your reloads, but you don’t want to pay for top-dollar dies, the RCBS Competition Die Set is a great option.

Please define “bullet runout” for us novices. I have an RCBS single stage press and a set of Hornady titanium nitride dies for .45 Colt–and haven’t ventured to other calibers as of yet. The Hornady set includes a neck expander and the seating die does an effective crimp, particularly on lead cannelured bullets. Measured OAL is quite consistent. And the titanium nitride dies do not require lube.

But that micrometer is pretty awesome; it will make repeatability of loading depth that much easier, and that window is a brilliant idea. I might have to look for one when I venture into reloading .308.

Bullet runout – in a nutshell, the degree to which the center line of the bullet does not sit along the center line of the case.. A large amount of runout would result in a bullet that visibly was tilted or shifted off the center line of the case. Sounds like this RCBS alignment sleeve holds the bullet straighter before it meets the case mouth, so the bullet is pointing straighter in the case – hope that makes sense.

It does quite well, and thank you. I assume that is much more of an issue with a necked case and ogived bullets, since straight walled cases and pistol rounds make that a pretty much impossible situation. The sleeve would essentially act lije a very ong neck to make the bullet verticle before it enters the actual neck. Interesting.