The Burris XTR II on the right is designed for quick turret adjustments, while the Eliminator III and Fullfield E1 have reticles designed for hold over shooting.

THE SERIES

- Part 1: Optics Buying Guide: Iron Sights, Red Dots, and Scopes

- Part 2: Optics Buying Guide: Top Must-Know Terms for Picking the Right Scope

- Part 3: Optics Buying Guide: Scope Mounts

- Part 4: Optics Buying Guide: How To Properly Zero Your Scope

- Part 5: Optics Buying Guide: Finding Your Range with a Scope Reticle

- Part 6: Optics Buying Guide: Hold Off vs. Adjustable Scope Turrets

- Part 7: Optics Buying Guide: Scope Reticles

- Part 8: Optics Buying Guide: Using a Laser Rangefinding Scope

- Part 9: Optics Buying Guide: Holographic and Red Dot Optics

- Part 10: Optics Buying Guide: AR-15 Optics and Scopes

- Part 11: Optics Buying Guide: Big Scopes

- Part 12: Optics Buying Guide: Do You Get What You Pay For?

I used to play a fair bit of golf in my younger days. One of the reasons I gave it up was the increasing frequency of my travels into other fairways – you know, the ones two counties to the right. I could hit the ball a country mile, but unfortunately, that “mile” was usually not in a straight-forward direction.

As with golf, you have to account for two variables in long range shooting – distance and lateral movement from the wind and other factors. In golf, you select your club and swing speed based on your best estimation of distance. And assuming you don’t have a wicked slice like me, you estimate how much the wind is going to blow your ball sideways and aim accordingly. When shooting long range, you don’t change clubs for distance, you adjust your scope, and you still adjust your aim point to account for the wind.

Let’s take a look at the lateral (windage) and vertical (elevation) factors for which we need to account. Then, we’ll consider different approaches to “dial those in” so we can hit targets with regularity.

Windage

For side to side variation, there are at least three factors that influence where a bullet is going to strike relative to your point of aim: wind, spin drift, and Coriolis effect. Fortunately, the only thing that most of us regular folks have to worry consciously about is wind. The wind has the greatest (by far) impact on how a bullet travels sideways when compared to the other two factors.

Spin drift, or gyroscopic drift as ballistic geeks call it, is the lateral movement of a bullet due to the air flow around it caused by its rotation. Using a barrel with a right-hand twist, bullets will tend to slide to the right over distance, maybe a handful of inches over 1,000 yards of travel depending on the specific projectile type. For our purposes, it’s important to recognize that spin drift impact is probably less than the precision with which we can account for wind. In other words, if we were able to measure the precise wind impact along the flight path to a decimal point or so, then we’d have to account for spin drift. If we’re estimating wind to the “nearest couple of miles per hour” then the spin drift effect will get buried in our imprecision.

Coriolis effect is fun to think about, but again not a big deal for us average long-range shooters. Since the earth spins, we’re all moving all the time. As I sit here in South Carolina, I’m booking along at about 900 miles per hour. When you’re out shooting, your target is too. So, while the bullet is in flight, the target is moving out of the way. It’s like a carousel. If you stand in the middle and throw a brick directly at one of the horses that don’t go up and down – because what good is a stationery carousel horse – the brick will fly behind the sedentary horse because the horse is moving forward as the brick is in the air. Fortunately, this effect isn’t a big deal either unless you need extreme precision at really long range. For something like a .308 round at 1,000 yards, the effect might only be a couple of inches.

Most scopes use 1/4 MOA (or 1/4-inch at 100 yard) click adjustments, although the Eliminator III integrated laser model offers 1/8 MOA adjustment.

Wind is what gives everyone fits because it’s so random. Not only is it hard to estimate with real precision, but it can also vary along the flight path. I’ve shot 1,000-yard scenarios where the wind is blowing in opposite directions at the shooting position and target. There might be wind at other speeds and from other directions anywhere in between. It’s like a golf putting green that slopes right, then left, then right again. As a result, making correct wind estimation is 50% science, 50% experience, and 94% VooDoo. Just a five mile per hour crosswind at 1,000 yards when shooting a Federal 175-grain Sierra Matchking load moves that bullet 53 inches by the time it reaches its target. That’s almost four and a half feet!

Elevation

Gravity causes bullets to drop a lot at longer ranges, but it’s very predictable. Unlike the wind, gravity doesn’t get moody – it’s amazingly consistent. If you know your bullet will drop 42 inches at some distance, it’s going to do that every time assuming similar atmospheric conditions. When the environment varies, you can easily calculate the impact of that change. The bottom line is that accounting for elevation is surprisingly easy once you get the hang of how the tools like ballistic calculators and scope adjustments work. If there is no wind, there is no reason you shouldn’t hit a 1,000-yard target every single time.

Determining your adjustments

Before you make adjustments to your scope turrets, you need to figure out what your windage and elevation compensation needs to be. Of course, before you do that, you need to estimate range and the wind. Range estimation is straightforward. You can use a laser rangefinder, or you can use your scope reticle and a bit of basic math. To learn more about this, see Finding Your Range with a Scope Reticle. Once you know the range, you can use smartphone ballistic apps or web-based ballistic calculators like Burris Ballistic Services to figure out the exact adjustments you need to make.

To make the necessary adjustments for distance and windage, you can take one of two approaches. You can adjust the turrets on your scope to “move the crosshairs” to compensate for distance and wind, or you can “hold over” by placing a different part of your reticle on the target. Neither method is right or wrong, they just have different advantages. Let’s take a look at four different ways to achieve these two types of adjustments.

Turret adjustments in mils or MOA

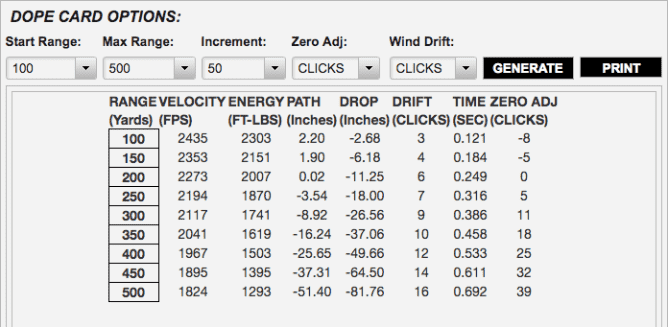

Most any ballistic software will not only tell you how many inches you need to adjust but will also tell you how many minutes of angle or milliradians will get you on target. For example, when shooting Federal 175-grain .308 Winchester, the Burris Dope Card online tool will tell us we need to adjust for 51.4 inches of drop at 500 yards, assuming we zeroed at 200 yards. In the example, I told the Dope Card tool that I was using a Burris Fullfield II scope, so it knows that each click of the elevation dial moves my point of impact 1/4 MOA. With this information, the tool tells me to adjust exactly 39 clicks for the 500-yard shot.

The Burris Dope Card online tool will give you exact windage and elevation data based on your ammo and conditions.

The benefit to this approach is precision and simplicity of aiming. Since you adjusted the turrets, you can put the fine crosshairs directly on the target and shoot. On the flip side, it’s not as fast as a “hold over” approach because you need to pause to make turret adjustments.

Reticle hold marks using mils or MOA

Some reticles use a system of hash marks to represent windage and elevation adjustments. The mil-dot reticle is a classic example. If our software tells us we need to adjust for three mils of elevation, we can just hold the third dot below the crosshairs on the target, and we’ll get a hit.

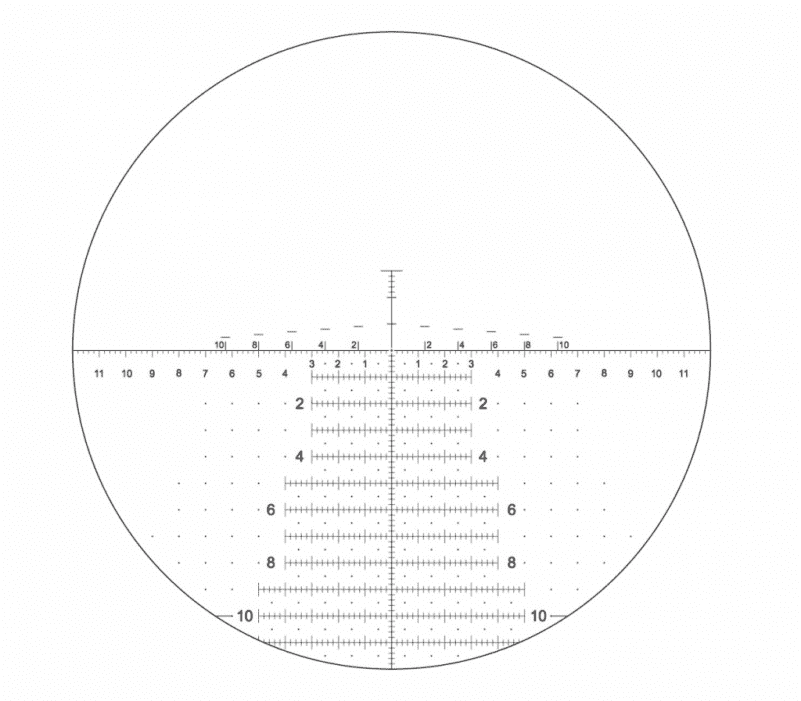

Many reticles offer marks that you can use for adjusting elevation, but some also offer advanced windage marks that allow you to account for crosswinds or even moving targets. A classic mil-dot reticle has dots for this purpose too. If you want even more precision, you can check out something like the Burris Horus H591 reticle. It uses a complex grid of fine hash marks for both windage and elevation. For example, you can easily find an exact hold point for an adjustment like 5.6 mils elevation and 3.4 mils left windage. As this reticle presents a precise grid, you just hold the intersection of those points on your target.

The Horus 591 reticle looks complex, but with practice you can make fast and accurate shots at varying distances.

If you need to make quick shots with a high degree of precision, consider a reticle designed for complex hold over targeting.

Reticle marks using ballistic drop compensation

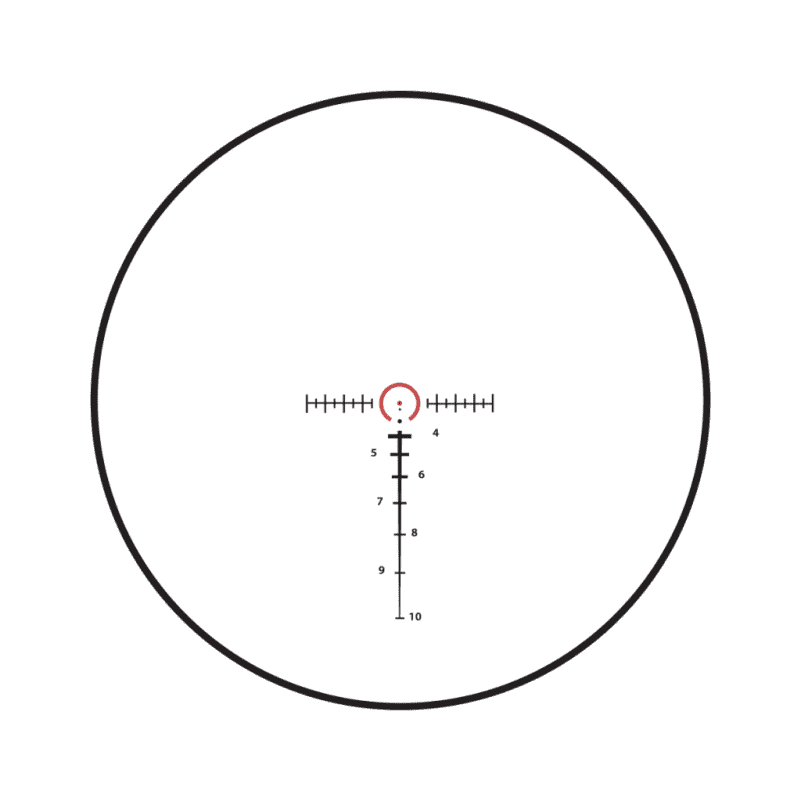

Ballistic drop compensation removes the complexity of figuring out minutes of angle or mils on the fly. The reticle itself shows you the yardage rather than MOA or mil marks. Reticles that use this approach are often designed for a specific type of ammunition. The Burris XTR II Ballistic 5.56 Gen 3 is a great example. If you need to engage a 600-yard target, just hold on the line marked with a six. It’s that easy. The downside is that these reticles are created for a specific ammunition load. If you use a heavier or lighter 5.56 bullet, your results will vary a bit. These reticles also cannot account for specific environmental conditions.

The Burris XTR II Ballistic 5.56 Gen 3 reticle shows holdover points for specific distances based on the average trajectory of the 5.56 round.

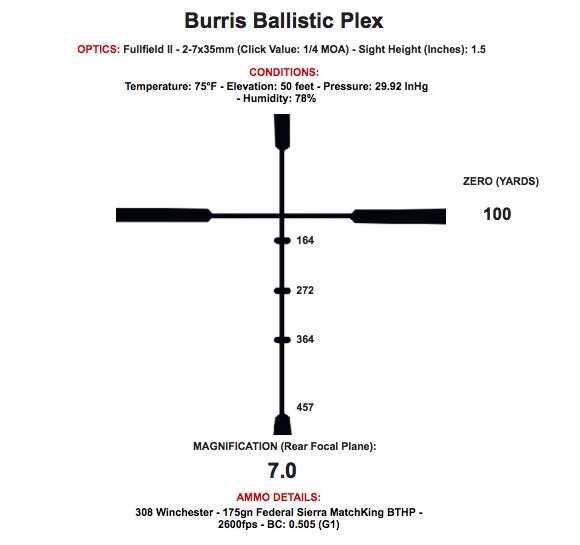

The other ballistic drop compensation approach relies on generic marks on the reticle. Rather than marking exact yardage indicators, you use online tools like the Burris Reticle Analysis to map yardages to marks. Simply fill out a couple of online forms with information like your reticle type, specific ammunition, and local environmental conditions. The calculator spits out a printout that shows the exact yardage of each reticle mark.

You can also use the Reticle Analysis tool to map generic reticle patterns to your specific ammo.

Turret adjustments using ballistic drop compensation

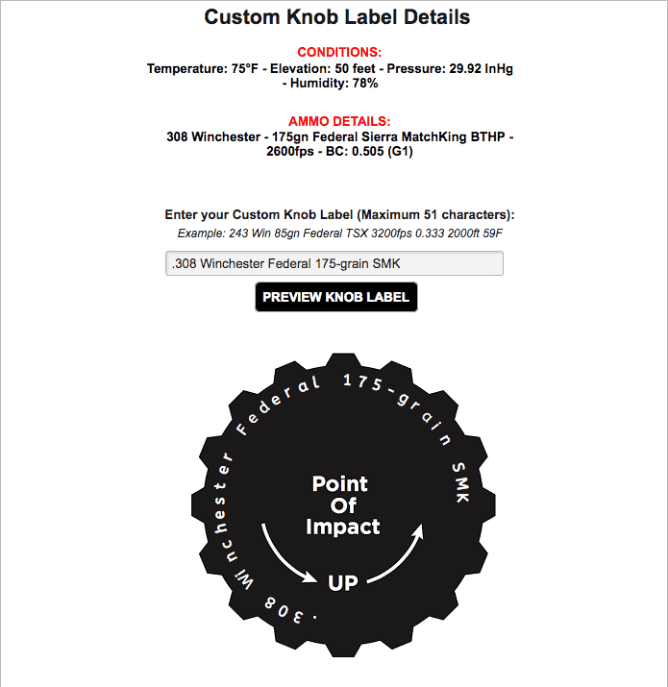

The last approach involves custom turret marking. Rather than using the factory-supplied turrets that indicate something like ¼ MOA per click, you use a software tool like the Burris Custom Knobs calculator to design your own turret markings. After you enter specific information about your intended ammunition and local conditions, the software will design a custom turret cap that’s marked with yardage instead of generic MOA or mil indicators. Order the cap, install it on your scope, zero your rifle, and you’re ready to go. Now, to engage a target at 500 yards, just spin the turret to the “5” and shoot.

Why not design custom turret knobs that indicate distances for your exact ammunition load and local environment?

While there are many approaches that achieve the same goal, they all boil down to making the adjustments necessary to account for distance and current environmental conditions. If the nature of your shooting is competitive, recreational, or even longer range hunting, and you have time before each shot, consider a turret adjustment solution. If you need to make quick shots on targets of varying distances, look at scopes and reticles designed for hold-over use.

For me – and I recognize this is more about individual \”comfort zone\” as opposed to right or wrong…

I prefer the Horus style reticles. Once I have zeroed at a known distance, and tested for bullet drop/drift at increasing distances out to 1000 yards and memorize the marks on my reticle which correspond to those distances I am satisfied. I never want to have to touch the turrets. But, this is because I primarily want to set up a rifle and scope for long range hunting. Though I do enjoy using the same weapons for shooting at steel just for fun.