To learn more, visit https://www.gunandswordcollector.com/Templates/book%20pages/canfield_BA.html.

To learn more, visit https://www.gunandswordcollector.com/Templates/book%20pages/canfield_BA.html.

To purchase a Model 1917 on GunsAmerica.com, click this link: https://www.gunsamerica.com/Search.htm?Keyword=1917<id-all=1&as=730&cid=440&ns=0&numberperpage=50&.

Editor’s Note: This piece is an abridged excerpt from the book U.S. Military Bolt Action Rifles by Bruce N. Canfield. If you would like to explore this subject in greater detail, you can obtain a copy of the 430-page book from Mowbray Publishing, 54 East School St., Woonsocket, RI 02895.

When the United States declared war against the “Central Powers” on April 6, 1917, it was obvious that there was an increased need for additional service rifles. The government had approximately 600,000 M1903 Springfield rifles on hand along with along 160,000 obsolete Krag rifles, which were totally insufficient to meet the project demand. Production of the M1903 rifle was ordered to be increased at both Springfield Armory and Rock Island Arsenal. The Ordnance Department consulted with Springfield and Rock Island engineers for ways to reduce production time and cost for ’03 manufacture but, without substantially redesigning the rifle to an unacceptable degree, only cosmetic changes could be accomplished. It was apparent that the combined output of these two national arsenals could not meet the burgeoning demand, and large numbers of additional service rifles would soon be needed.

The Ordnance Department determined that it had two basic options to procure the additional rifles needed: The first option would be to seek additional manufacturing sources for the M1903 rifle. The second option would be to adopt a second type of service rifle to augment the M1903 rifle.

The first option was explored at length, but it was eventually determined that the lag time required to find suitable firms capable and willing to manufacture the ’03 rifle, negotiate contracts, procure the necessary materials and machinery and train workforces would be too great to alleviate the potential crippling shortage of rifles. Thus, almost by default, the Ordnance Department was left with Option #2 as the only viable alternative.

It is sometimes said that “timing is everything” and, in this instance, that proved to be true for the United States military. As events transpired, there was a source for manufacturing modern military service rifles that could go into production in a relatively short period of time. This fortuitous happenstance was due to the fact that when the United States declared war, three American plants were completing production of the “Pattern 1914” rifle under contract for the government of Great Britain. The Pattern 1914 rifle was a slight modification of the “Enfield .276-inch Magazine Rifle,” also known as the “Pattern 1913 Rifle.” The Pattern 1913 was a modified Mauser design and was chambered for an advanced .276 caliber cartridge and was intended to replace the venerable Lee-Enfield .303 caliber rifle.

By the time that testing and modification was completed on the new rifle, Great Britain became embroiled in the conflict that came to be known as the “World War.” The dire need for additional service rifles resulted in the British putting the .303 caliber SMLE Lee-Enfield back into production. In order to further boost production, it was decided to manufacture the Pattern 1913 rifle as well, although the novel .276 cartridge was to be replaced by the standardized .303 cartridge in order to reduce supply problems. This change in cartridges required a new “Pattern” (model) designation, and in October of 1914, the “.303 Pattern 1914 Rifle” was adopted.

In order to procure the necessary rifles, Great Britain looked to the United States and, eventually, production contracts for the Pattern 1914 rifle were given to three American firms: Winchester Repeating Arms Company (New Haven, Connecticut), Remington Arms Company (Ilion, New York) and an affiliate of Remington in Eddystone, Pennsylvania, that was eventually known as the Midvale Steel & Ordnance Company. Despite the usual glitches and delays in getting into production, the three companies eventually manufactured a total of 1,235,298 Pattern 1914 rifles under British contract by the time production ceased in July 1917.

Fortunately for the United States, the workforces and production machinery used to manufacture the Pattern 1914 rifle were still essentially intact, thus the three firms could almost immediately go into production for the American government. While the United States was unquestionably fortunate to have production facilities for the Pattern 1914 rifle on hand and ready to go back into production, the Ordnance Department was faced with yet another dilemma with three possible options: The first would be to convert the three plants from Pattern 1914 production to manufacture of the standard M1903 rifle. This option would require extensive delays in getting into production on a totally new weapon.

Two World War I-era U.S. Doughboys posing with their Model 1917 rifles. Note the bayonets attached to cartridge belts.

The second option would be to adopt the British Pattern 1914 rifle “as is.” The advantage of this approach is that it permitted the maximum number of rifles to be manufactured in the minimum amount of time. The major disadvantage would be the introduction of a non-standard cartridge into the military’s inventory with the resultant probability of troublesome supply problems. Also, the British .303 was widely viewed by the Americans as somewhat inferior to the U.S. .30-06 cartridge.

The third option would be to modify the Pattern 1914 rifle to accept the standard U.S. .30-06 cartridge. The downside of this approach would be a delay in getting the modified rifle into production. However, this course of action would result in a rifle chambered for the standard and superior U.S. cartridge.

After studying the various options, the Ordnance Department selected option number three, and plans were made for American ordnance engineers to go to work modifying the British rifle to accept the U.S. service cartridge. The modified rifle was adopted as “United States Rifle, Caliber .30, Model of 1917.”

From a technical standpoint, converting the Pattern 1914 rifle to chamber the .30-06 cartridge was not particularly difficult. The weapon possessed a strong nickel steel action that could handle the powerful .30-06 round with no problems. The fact that the Pattern 1913 rifle was originally designed for use with a rimless cartridge (the .276) actually made the Model 1917 rifle more suited to the .30-06 cartridge (also rimless) than the rimmed .303 round.

On May 10, 1917, each of the three manufacturers (Winchester, Remington and Eddystone) sent to Springfield Armory a sample of a Model 1917 rifle fabricated by the respective companies for evaluation and testing. The fact that most of the parts of each rifle were hand-fitted resulted in a lack of interchangeability of the majority of the components.

Eventually, standardized manufacturing specifications and drawings were finalized, and large numbers of Model 1917 rifles began to flow from all three plants. While the interchangeability problem was never totally eliminated, a 95% interchangeability rate was established, which was acceptable to the Ordnance Department.

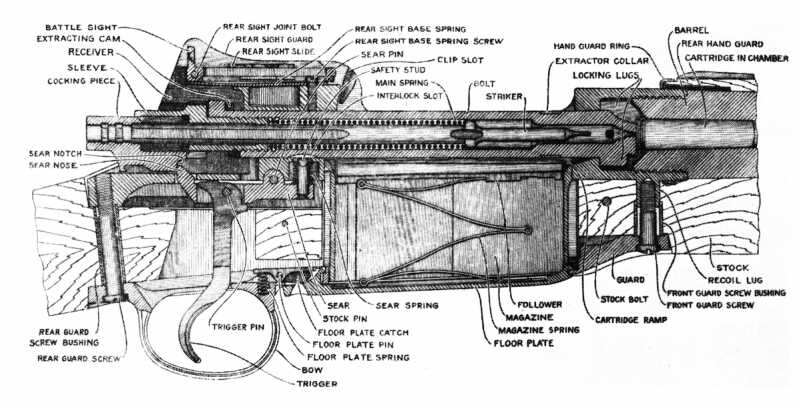

The Model 1917 rifle was 46.3 inches in overall length with a 26-inch barrel. The weapon weighed 8.18 pounds and had a magazine capacity of six rounds. The same type of 5-round charger (i.e., stripper clip) used with the ’03 rifle was also utilized with the Model 1917. This resulted in five rounds being routinely carried in the magazine, although a sixth cartridge could easily be manually inserted if desired. The rear sight had a folding leaf adjustable for elevation but not windage. The sight was mounted on the rear of the receiver, which made it a better battle sight than the Model 1903 Springfield’s M1905 rear sight. The front sight blade was protected by two sturdy “ears” on either side. The stock and two-piece handguard were made of oil-finished black walnut with grasping grooves milled into both sides of the fore-end. The external metal parts were blued.

One attribute of the Pattern 1913/14 rifle that remained on the Model 1917 was the “cock-on-closing” action. The Model 1903 Springfield rifle with which most of the American doughboys were accustomed featured a “cock-on-opening” action. This resulted in many complaints against the Model 1917’s operation, primarily due to the lack of familiarity.

A distinctive feature of the Model 1917 rifle was its “crooked” bolt handle. This design enabled the bolt handle to be in close proximity to the trigger, which assisted in faster operation of the bolt. The Ordnance Department believed that this feature was quite valuable and stated that it permitted the Model 1917 to be fired twice as fast as the German Mauser rifle with its straight bolt handle.

The receiver ring of the rifle was stamped “U.S./Model of 1917/ name of maker/serial number”. The barrel was stamped on top (behind the front sight) with the initials of the maker (“W”, “R”, or “E”), a flaming bomb insignia and the month and year of production. The receiver ring of very early Winchester rifles was simply marked “W” (as was the case with the British Pattern 1914 rifles) below the “U.S.” However, this feature was soon eliminated, and the vast majority of the rifles made by the firm were marked “Winchester” on the receiver ring. Serial numbers were sequentially applied beginning with “1”.

The exterior metal parts of the Model 1917 rifles were finished in rust bluing. While the tint and texture of the blued finish could vary a bit during the course of manufacture, the workmanship was always first-rate. The stock and handguards were made of quality black walnut and were crafted and finished with the same level of craftsmanship as the armory-made Model 1903 rifles of the era. Bluing was used throughout production of the Model 1917 rifle with the exception of late-production Eddystone rifles, which were factory parkerized beginning circa October or November 1918. After the war, the vast majority of Model 1917 rifles made by all three contractors were overhauled, which almost always resulted in the formerly blued rifles being parkerized as part of the rebuild procedure. The factory-parkerized Eddystone rifles are quite scarce today, and relatively few were made and most were subsequently reparkerized after the war. Likewise, any Model 1917 rifle extant that retains its original factory blued finish is fairly uncommon, and examples are avidly sought by today’s collectors.

Many components of the Model 1917 rifle were stamped with the first initial of the maker (“R”, “W” or “E”). These parts included the tip of the stock, bolt, rear sight and safety. The stock was normally stamped on the bottom in one or two locations with a small eagle-head proof marking often found on other WWI-vintage U.S. military firearms including the Colt M1911 .45 pistol.

Because of its excellent battle rear sight and other virtues such as sturdiness and reliability, the Model 1917 soon proved its worth as a combat weapon to the initially skeptical Doughboys. There were also some deficiencies of the new rifle that were revealed as it began to see use in the stateside training camps. While some of the defects were traceable to the sometimes faulty wartime ammunition, there were other problems encountered, including an inordinate number of broken ejector springs and extractors as well excessive headspace. It was reported that one U.S. Army infantry battalion had 149 of their Model 1917 rifles (all made by Remington) exhibit excessive headspace. Another feature of the Model 1917 rifles that some soldiers found annoying was the fact that the rifle did not have a magazine cut-off, which meant that the follower blocked the closing of the bolt when the magazine was empty. A stamped sheet-metal “magazine platform depressor” was issued, which eliminated the problem.

As stated, the “cock-on-closing” action was also unpopular with many Doughboys who were accustomed to the Springfield’s action. The lack of a cocking piece on the bolt was also cited as a deficiency in the eyes of some users.

World War I soldier in full gear shouldering his Model 1917 rifle. Image courtesy of The National Archives.

In order to familiarize the soldiers with the new rifle and minimize negative reaction to the real or perceived problems, the Army assigned “Demonstrators” (usually junior officers) to the various training camps. These Demonstrators conducted training courses with the Model 1917 rifle and submitted written reports detailing their activities at each facility.

As production continued and some of the nagging problems were worked out, more and more Model 1917 rifles were shipped to France for issuance to the Doughboys of the American Expeditionary Force. On March 2, 1918, the Chief of Ordnance was ordered to replace Model 1903 rifles with Model 1917 rifles. The orders read, in part:

“You will take immediate steps to substitute model 1917 rifles for model 1903 in all organizations except Cavalry and Mounted Engineers…This exchange will include all appendages, spare parts and pertaining equipment not interchangeable between the two arms.”

The Model 1917 rifle acquitted itself very well on the battlefields of France and, as they gained experience with the weapon, fewer soldiers complained about having to use an American Enfield rather than a Springfield. There were many reports regarding the efficacy of the new rifle with relatively few detailing any significant problems. The most famous Doughboy of them all, Alvin York, was issued a Model 1917 rifle and used it rather efficiently. Some individuals today are of the opinion that York actually used a Model 1903 rifle, but there is very convincing evidence that the intrepid Tennessean did, in fact, use a Model 1917 during his famed exploits. York’s use of the Model 1917 rifle was briefly discussed in the classic book The Doughboys by Laurence Stallings:

“…York now holstered his pistol and thumbed a fresh clip into his Enfield…It was difficult for York’s Germans to discern whence came this murderous fire. What ear could distinguish the well-aimed single shots of an American-modified Enfield rifle amidst the chatter…”

By the time of the Armistice, it is reported that some 1,123,259 Model 1917 rifles had been shipped to France with 800,967 issued to troops and 322,292 “…floated in bulk” (unissued in reserve). Of this figure, 61,000 were reportedly issued to the U.S. Marine Corps and 604 to the U.S. Navy. In addition, 127,000 Model 1917 rifles had been issued to U.S. military personnel still in the United States and another 70,940 were on hand at various ordnance facilities and military installations.

These figures represent substantially less than the over two million Model 1917 rifles that were eventually manufactured by Winchester, Eddystone and Remington, and the difference was primarily rifles that were manufactured after the Armistice but prior to cancellation of the production contracts. The number of M1917 rifles manufactured during this period was substantially greater than the number of M1903 rifles, and by the time of the Armistice, an estimated 75% of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) was armed with the “American Enfield.”

These figures represent substantially less than the over two million Model 1917 rifles that were eventually manufactured by Winchester, Eddystone and Remington, and the difference was primarily rifles that were manufactured after the Armistice but prior to cancellation of the production contracts. The number of M1917 rifles manufactured during this period was substantially greater than the number of M1903 rifles, and by the time of the Armistice, an estimated 75% of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) was armed with the “American Enfield.”

To learn more, visit https://www.gunandswordcollector.com/Templates/book%20pages/canfield_BA.html.

To purchase a Model 1917 on GunsAmerica.com, click this link: https://www.gunsamerica.com/Search.htm?Keyword=1917<id-all=1&as=730&cid=440&ns=0&numberperpage=50&.

Editor’s Note: This piece is an abridged excerpt from the book U.S. Military Bolt Action Rifles by Bruce N. Canfield. If you would like to explore this subject in greater detail, you can obtain a copy of the 430-page book from Mowbray Publishing, 54 East School St., Woonsocket, RI 02895.

I traded for a Winchester 1917 about 25 years ago. I was starting gunsmithing school and needed a project rifle. I removed the barrel and stock, and milled the rear sight ears off. Built a 358 Norma mag, half round half octagon barrel for it, and a sporty Claro Walnut stock. Made scope mounts for it and put a nice big Weaver on it in Talley rings. It’s hell-for-stout, pleasingly accurate, and roars like a T-Rex when it goes off, but recoil is surprisingly tolerable. It’ll never have the elegance of a Mauser, but the elk don’t care.

My husband bought me a US Model 1917 Eddystone rifle to hunt deer with bout 20 some yrs ago. We have taken many deer and wild boar with it over the years as well as target shooting at our annual BBQ/shoots. It will out shoot our 03s, Krags, and even some of our M1 Garands. NEVER had any problems with it. A true piece of history and a pleasure to shoot and own. CiscoKid is wrong. Maybe he got a worn out junk rifle. We will never sell it and my oldest son now hunts with it as well. Trust me, this is a GREAT rifle to own.

Never once read anywhere of a 1917 blowing up. That was with Springfield rifles up to number 803,000, and Rock Island up to about number 285,500. 1917 rifles have been converted to large magnum calibers, it can’t be done with 1903 model. U.S. gave them to countries because they were not the “official” rifle for the U.S. armed forces and were declared surplus. Some M.P. and mortar men were equipped with 1917 rifles in WW II. I owned 2 of each model, and they were equal in quality and accuracy.

I have a sporterized 30-06, which someone tried to equip with a scope, holes are crooked, but I also have the original stock of the Enfield m1917 eddystone, if anyone wants it. $350 . I am tired of it already.

Good article I have a 1917 lee Enfield my grandpaw converted I’m til a hunting rifle has a beautiful rosewood srock. He killed a lot of elk in his day with it .Is a great shooter

I have owned a model 1917, (sold along with many other firearms for a down payment on my first house years ago) and still currently own a model 1914 .303, both Eddystones, and are very quality made rifles, and I actually prefer them to the 1903 A3 I own.

As you state the 1903 had heat treating problems as well as others, I have fired hundreds of rounds from these rifles with absolutely no problem whatsoever, if I had to choose going into battle right now with a 1903 or a 1914 or 1917 I would go with the latter.

Just my two cents.

For those of you that want the true story about the most hated bolt action rifle the Military ever adopted read “The 1917 Enfield Rife” by Ferris available from the NRA in paper back. It details the disaster the gun really was. It too blew up because of faulty heat treatment just like the early 1903 Springfield Rifle did.

It was built with no blue prints, only drawings and most parts are not even interchangeable especially when changes were made to the design of the various parts as the gun was being produced.

The gun was so hated that major news papers ran editorials warning the military not do adopt it.

At the beginning of WWII when the U.S. desperately needed rifles the Government dumped thousands of them on other countries just to get rid of them so the troops would not have to use them in WWII. That is why although there were far more of them made in WWI than the Springfield Rifles they are much more scarce today on the collector market but they still bring less money when offered for sale.

When the author was researching the book he had 11 rifles for reference and suddenly noticed all 11 of them were not of the same overall length. The workmanship was actually that bad. The gun also suffered from broken ejectors as well.

The worst model to collect is the Eddystone manufactured guns. They had the worst workmanship.

I strongly recommend you read the book as it cuts through all the patriotic nonsense articles written down through the years on this weapon.