A traditional bowhunter is offered a mid-range shot at a moving bull elk. Should he take the shot?

LONGBOW ELK SCENE

The afternoon was long and I’d been on the trail of these elk all day. We first found them by the sound of bugling bulls and chirping cows, deep in a big mountainside burn. This was a large herd, with a lot of cows and a handful of nice satellite bulls tormenting the herd master; a beautiful seven-by-seven monarch. He wasn’t a high-scoring bull, but he was symmetrical and lovely.

Nine days I’d spent in these mountains, nine glorious days of climbing, glassing, and stalking. I’d had several close calls with great bulls, but it’s never easy to close within the longbow range of any animal. Things just hadn’t quite come together yet. I needed to be just a little closer, just a little stealthier. I was tuned in and hungry now, and lurking like a downwind shadow to these elk. Sooner or later one of those nice bulls would circle my way. Perhaps it would be the big herd bull.

BOW AND BROADHEADS

I’d drawn a coveted archery elk tag for Northern Wyoming and legally could use a compound, recurve, or longbow. I’m a passionate traditional bow hunter, and while I will use and enjoy shooting and hunting with a compound bow, I prefer the simplicity of a stick and string. This hunt promised to be a good one, with reports of good numbers of elk and stalkable terrain. So I chose to hunt with my favorite longbow, a superb example of the bowyer’s art made by Ron King of Fox Archery in Oregon. The bow is a Royal Crown model, 62 inches tip-to-tip and 55 pounds at 28 inches of draw, and had won a blue ribbon at the 2006 Professional Bowhunters Society Convention. I bought the bow when it was auctioned later that night, and immediately fell in love with it.

ARROWS

My personal draw length is 29.5 inches, so given the extra draw length my new Royal Crown pulled 59 pounds at full draw. For arrows, I chose Beman classic 400 shafts and fletched them with three 5-inch shield-cut left-wing feathers. I cut the shafts at 30 inches and carefully epoxied the threaded inserts in place. My favorite broadhead for this setup is a fixed 3-blade 125-grain Woodsman, mounted on a 125-grain steel adaptor, giving a total broadhead weight of 250 grains. This head provides a 3:1 length-to-width ratio, which is ideal for penetration. Such a heavy broadhead/adaptor combination sets up my arrow with tons of FOC (forward of center), also good for penetration.

I spin each broadhead on each arrow and adjust till they spin perfectly. I also orient the top blade of the three vertically so that my subconscious sight picture is consistent from arrow to arrow. Total arrow weight is 590 grains, and arrow velocity is around 190 feet per second. Selway Archery makes my preferred traditional quivers, so I mounted a 5-arrow Selway to my longbow and carefully installed the broadhead-mounted arrows.

Available on GunsAmerica Now

I shoot traditional bows instinctively, using no sights whatsoever. It’s a fast and effective system, so long as you develop consistent form and draw length. Beyond about 30 yards I transition to a sort of subconscious gap-shooting method, using the tip of the arrow as an aiming reference. When I’m in good shooting form I’m lethal on elk-sized targets out to about 45 yards. But that’s a long poke with a longbow, and conditions must be just right before I’ll take that shot on a game animal.

LONGBOW ELK LOCATION

I’d driven across two states to reach my hunting area, and now I was camped with friends in a beautiful spot far from any highway. Elk habitat stretched away in every direction, but the animals seemed to prefer the high steep slopes of the peaks. This was early September; too early for them to begin migrating toward the lowlands. So each morning we would leave camp before daylight, cross the frosty meadows, climb to high vantage points to glass, and listen for rutting elk. Almost every day we got into them, stalking, failing, and stalking again. It was the kind of territory that is conducive to effective traditional bowhunting, and I knew it would just be a matter of time until things came together.

THE HUNT

Time was growing short on the ninth day of hunting, and we struck off in a different direction than we had previously hunted. A big burn rolled along the base of the mountains, blackened timber reaching lonely trunks toward the sky. We heard the elk before we saw them, bugling and feeding through the burn. Stalking close, we watched them as they fed and rutted along the mountainside, assessing the bulls and hoping for a good opportunity for a stalk.

We shadowed the herd for an hour or more before the morning thermals caught us unprepared and gave the elk a whiff of our scent. Trotting across a small canyon bottom, they climbed a steep avalanche chute on the other side and disappeared over the ridge into a huge, undulating canyon. We backed out and headed back to camp for some lunch.

SEE MORE: Take the Shot? A Mature Kudu Bull Offers A High-Speed Opportunity

Midafternoon found me climbing the ridge above the undulating canyon, peering into hollows and shadows, and listening for elk. I figured they would be tucked away somewhere shady and cool and out of sight. Sure enough, I finally heard bugling and, slipping closer, saw the elk. Satellite bulls still tormented the herd bull, keeping him on his feet and moving. The elk were up and feeding, starting their evening descent into the canyon bottom to graze on the small meadows there.

Back in shadow mode, I followed, hoping for one good opportunity. Several times I was within range of cow elk, moving like cold molasses, doing my best to remain undetected. I figured sooner or later the herd bull would push another bull around to my edge of the herd, giving me a shot at one or both of them.

THE MOMENT

Most of the elk had made the canyon-bottom meadow and were fanning out, feeding on the succulent forbs and grasses there. Crawling low, I advanced to the edge of the meadow, hiding among some boulders. To my dismay, the big seven-by-seven herd bull was far out among the cows, well beyond the reach of my longbow. I settled onto my knees and knocked an arrow. All I could do now was wait and hope. I studied the timber where elk still streamed slowly into the meadows; some of the nice bulls hadn’t yet shown themselves.

The sound of running hooves from the meadow caught my ear and I rose up to look. One of the satellite bulls was running straight at me, the big herd bull hot on his heels, 40 yards out and closing. Sinking back to my haunches I raised my bow and waited. Only seconds passed before antlers showed above the boulders, walking steadily toward and left of my position. I drew my bow, and as the bull cleared the rocks, walking broadside at 23 yards, I focused on his vitals. It was not the big bull, but one of the satellites. The big bull might, just might, follow him.

TAKE THE SHOT?

Place yourself in my shoes. You’re at full draw on a nice Wyoming bull. The range is not excessive. But he’s walking, complicating the shot. Furthermore, the big bull you’ve been watching could follow, offering the opportunity you’ve been hoping for.

This is the first good shot opportunity you’ve had in nine days of hunting. Will you take the shot?

HERE’S WHAT HAPPENED: TRUE STORY

I took the shot. Based on my experience with elk, the herd bull was likely to stop at the edge of the meadow and watch the satellite bull depart into the boulders and trees. Then he’d turn back to his herd. Sure, I might fling a shot at him meanwhile, but it would be a bit of a Hail Mary attempt. This shot in front of me was what traditional bowhunters dream of. Sure, it was a little long and the animal was moving, but elk make a big target and I knew I could kill this one.

\I drew my bow before his eye cleared the rocks; he had no clue I was there. As soon as he came broadside I waited till his near foreleg swung clear of the vitals and I dropped the string. The arrow disappeared through his lungs and, startlingly, flung high into the air, spinning like a ceiling fan. For a moment I thought that somehow I’d missed the elk, but then remembered seeing the arrow vanish through his thorax.

The bull spun away and dashed downhill through a thick patch of timber. A huge crash sounded up the mountainside. The double-lung hit had completed its work in seconds.

CONCLUSION OF THE LONGBOW ELK HUNT

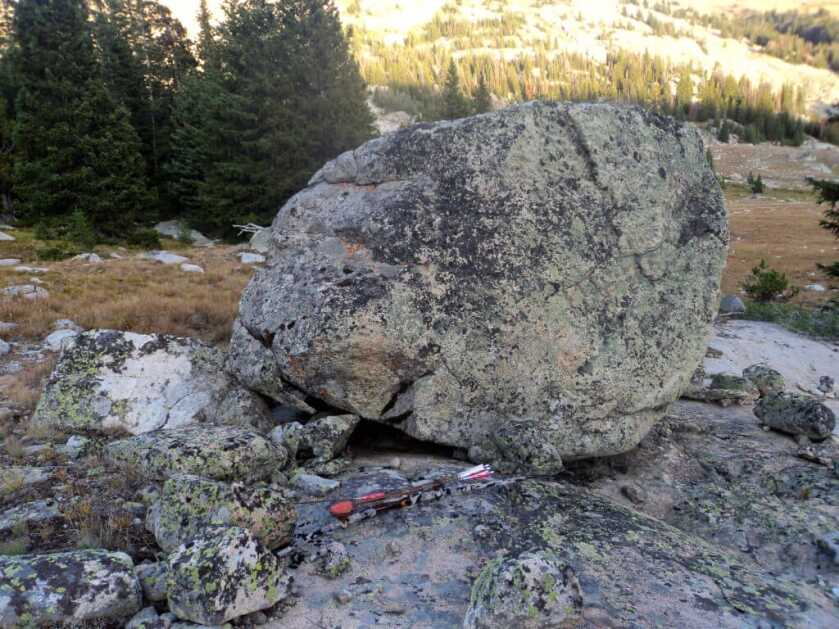

I watched the rest of the elk stream away, winding up the far canyonside, chirping and bugling as they went. Then I stood and walked to where my arrow lay, bathed in bright blood from end to end. Picking it up, I looked at the blunted tip and then at a giant eight-foot-tall boulder, sitting just beyond where the elk had been when my arrow zipped through him. The arrow had still possessed enough speed and energy to glance off that giant boulder, spinning high into the air.

The rocky ground was bathed in blood where the elk ran. I followed an ample blood trail through the timber, finding my high-country bull right where I’d heard the crash a short time before. Setting my longbow aside I snapped a couple of photos and began the age-honored task of skinning and quartering the bull. It had been a good hunt, a good shot, and a good bull.

Would you take the shot? I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comment section below.

*** Buy and Sell on GunsAmerica! ***

Aram, congratulations on your bull! I too am a member of PBS. I joined back in 1991 when I started shooting traditional bows. You took an ethical well practiced shot. I may not have taken it as my practical, ethical range is 15yds. Of course this is on a whitetail. With enough practice I might take the shot. Shooting at moving game has always been a “no go” for me. But that’s me.

Every hunter must set a standard which he/she will not violate no matter what. I’m glad you stayed with in yours and succeeded.