Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

According to its website, the American Medical Association is the, “Largest and only national association that convenes 190+ state and specialty medical societies and other critical stakeholders.”

Their stated mission is to, “Promote the art and science of medicine and the betterment of public health.” I’m a physician, but I’m not a member of the AMA. Lots of other doctors aren’t, either.

According to Physicians Weekly, only 15-18% of American physicians were paying members of the AMA in 2015. The AMA pads its membership numbers with free enrollments for medical students and residents, but most practicing physicians are not members of the organization. In my case, my decision to divest from the AMA was driven by some fundamental disagreements over policy.

Leftists are forever foisting their ideals upon others. They really cannot seem to help it. People will always disagree–that’s part of the human condition. However, some people become so entrenched in their own worldviews that they simply cannot rest until the rest of humanity falls into line. By contrast, I don’t much care what other folks do so long as they just leave me alone.

Table of contents

The American Medical Association

I need a professional organization that applies collective influence to restrain greedy health insurance companies, lobby the government on my behalf, and confront predatory plaintiff’s attorneys, not champion left-wing political causes. However, AMA’s policy paper H-145.993 dated 2018 states that, “Our AMA supports appropriate legislation that would restrict the sale and private ownership of inexpensive handguns commonly referred to as “Saturday night specials,” and large clip, high-rate-of-fire automatic and semi-automatic firearms, or any weapon that is modified or redesigned to operate as a large clip, high-rate-of-fire automatic or semi-automatic weapon and ban the sale and ownership to the public of all assault-type weapons, bump stocks and related devices, high capacity magazines and armor-piercing bullets.”

“Large clip, high-rate-of-fire automatic and semi-automatic firearms.” Um, yeah. In our world that’s the mark of somebody who hasn’t a clue what they’re talking about. Good luck adjudicating that one in court. Additionally, their take on abortion and a few other hot-button issues makes the AMA ineligible for my support. There’s really no reason for the AMA to take official positions on stuff like that, but, like I said, they really can’t seem to help it. That’s one of the big reasons 82% of practicing physicians aren’t members.

To their credit, misguided though they may be, the underlying impetus is indeed altruistic. All physicians, even the crappy ones, are initially drawn to the profession out of a desire to help people. It’s kind of what we do. Sometimes that sense of altruism gets beaten out of you over time, but we all start out in roughly the same place philosophically. To a degree, the AMA reflects that ethos. However, that’s not the space from which the American Medical Association first arose.

Background

It’s pretty tough to get into medical school these days. It’s even tougher to stay there once you get in. However, that was not always the case.

Back in the early 1800’s, medical training wasn’t a grueling competition followed by seven to ten years of soul-sucking misery. Back then becoming a doctor was actually pretty easy. Of course, your primary diagnostic and therapeutic modalities were typically limited to stuff like bleeding sick people white, tasting their urine for sugar, and administering tobacco smoke enemas. There just wasn’t so much to learn back then. As a result, there were professional practitioners of the healing arts just about everywhere. They frequently pulled teeth, embalmed bodies, and cut hair on the side just to make ends meet.

The Medical “Problem”

In the early part of the 19th century, America was churning out five times as many physicians per capita as was Europe. The practice of medicine was a sweet hustle, and lots of folks wanted in on the racket. Eventually, there weren’t enough sick people to go around. The resulting competition resulted in some surprisingly dangerous levels of vitriol. One Philadelphia sawbones of the era lamented that his colleagues, “Lived in an almost constant state of warfare.”

It was not unusual for these professional healers to come to blows over the right to treat some person or another. Considering the global life expectancy during this sordid period was only 29, there just wasn’t enough business to go around. Sometimes things got out of hand.

The Solution

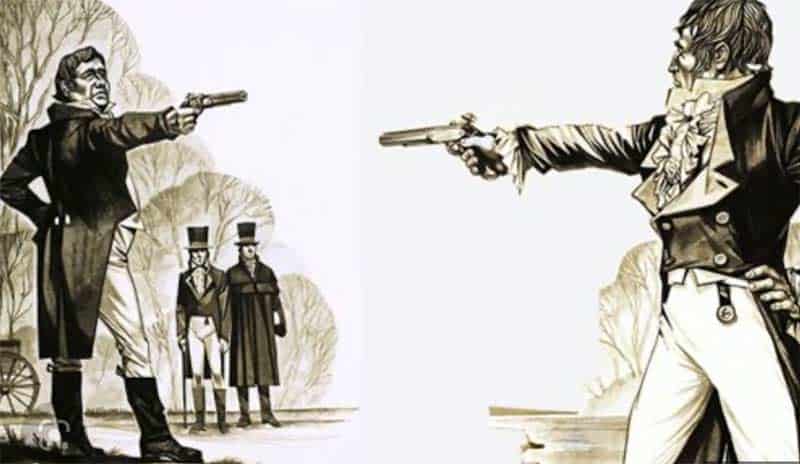

One fine summer day in 1818, Dr. Benjamin Dudley had just wrapped up an otherwise routine autopsy. A fellow practitioner named Dr. Drake took issue with some of his methods. Tempers flared until Dr. Dudley felt that his honor had been impugned. He therefore formally challenged Dr. Drake to a duel.

READ MORE: Dr. Dabbs – Ralph Goranson: The Real Captain Miller

Then as now, dueling as a means of settling grievances did not exactly enjoy universal appeal. In fact, Dr. Drake opposed the practice on principle. However, in an example of just how weird things were back then, a third physician named Dr. William Richardson volunteered to take Drake’s place on the field of honor. That either meant that Doctors Drake and Williamson were really, really good friends or that Dr. Dudley was just a jerk in desperate need of a trouncing. Regardless, the stage was set for an epic scrap.

Dueling was well frowned upon by the authorities of the day. Even if you were fortunate enough not to be shot to death, there was a fair possibility that the surviving duelist would nonetheless be arrested. However, these guys were clever and conjured up a brilliant remedy. The two men–the offended party and the stand-in–therefore set a date along with a unique location.

The Duel

Dueling was quite a social event, so both men arrived on the appointed day with a generous array of friends and strap hangers. Local surgeons and their flunkies were well represented. The location for the fight was to be a curious spot in Central Kentucky some 6.5 miles west of Lexington near the Transylvania Medical School. This was not the first time locals had need of such a venue.

This location was chosen with great care. Once they got their affairs in order, one man stood in Scott County, while the other arranged himself in Fayette. The county line demarcated between the two. If they should be discovered conducting an illegal duel, the fact that each perpetrator was in a separate county made local prosecution all but impossible. How clever was that?

As decorum demanded, each man deferentially bowed to his opponent while their seconds loaded pistols. They carefully arranged themselves on the appropriate pieces of turf, while someone tossed a coin to determine who would do what. Both men took up their single-shot dueling weapons and stared deeply into their opponent’s eyes. When the time was right, whoever was running this freak show commanded, “Fire!” and both men touched off their pistols at the same time.

What Happened

Dudley was unharmed, but the stand-in Dr. Richardson caught a ball in the groin. The injured man fell ignominiously to the ground in a heap. The nearest physician leapt into action but was unable to staunch the bleeding. Apparently, a significant femoral vessel had been violated, and now this kindly volunteer was trying desperately to bleed out.

Dr. Dudley’s healing spirit regained sway, and he was at the injured patient’s side in moments. Dudley slowed the bleeding with direct pressure and then sewed the damaged plumbing on the spot. In so doing he addressed the wound he had moments before inflicted and saved the poor fellow’s life. It’s rare that a duelist might push aside all ideological differences in order to save the life of a man who had so recently been trying to kill him. What a bizarre turn of events…

The Rest of the Story

That sordid duel precipitated a curious sequence of events that ultimately led to the formation of the American Medical Association as an exclusive social club of sorts. Concerned physicians appreciated that such antics reflected poorly on the professional credibility of doctors everywhere. As a result, by the mid-1840s, local docs began meeting informally to air their grievances and decompress, ideally before anything got out of hand. In 1847, these physicians formally established the American Medical Association.

The AMA fostered collegiality and helped begin regulating some of the insane medical treatments in common use at the time. Thus began the slow slog toward evidence-based medicine that drives our profession today. Despite all that other stuff, however, one of the earliest mandates of the AMA was to, “Foster…friendly intercourse between doctors.” That word clearly meant something different back then.

What The Medical Association Means Now

Nowadays those who can do, and those who can’t administrate. The practice of medicine is a really busy gig. In my own clinic, lunch is a luxury. Those of us living amidst COVID-19, flu, hemorrhoids, and venereal diseases frequently lack the discretionary time to pontificate much about social justice. This can lead those who reliably attend conferences with like-minded souls to believe that everybody feels as do they. That simply is not the case.

Whether it is the AMA, the NRA, the AFL-CIO, or any number of other storied alphabet organizations that might have been around long enough to have outlasted their welcome, they often lose touch with the little guy for whom they’re supposed to advocate. Having perused their policy statements, one could be forgiven in the Information Age for presuming that the AMA had forever been a hotbed of anti-gun liberalism. However, the reality is far stranger. The American Medical Association technically had its earliest origins in two physicians who tried mightily to snuff each other’s mortal flicker at the muzzle of a handgun. Fortunately one of the pugilists ultimately chose to save life that day rather than take it. Sometimes it’s indeed a weird old world.

*** Buy and Sell on GunsAmerica! ***

Doc:

I too, have defunded the AMA. Policies that are not directly part of our vocation should not be enacted by our VOCATION ASSOCIATION. Further policies centering on critical race theory instead of championing the meritocracy have confirmed that I have made the correct decision. Personally, I do not care where your race, religion, sexual orientation, or personal ethos lie when I need a competent physician. I am more interested in getting my loved ones the appropriate care they need than I am concerned over what the provider looks like. I understand there are social and ethical barriers to care that arise frequently in my practice; therefore, I strive diligently to have an independent interpreter and understand the limitations that will occur in a mixed ethnic environment. As to the fate of the AMA, I am sure that we now have less than 15% of practicing physicians in the organization. Personally, I think we need a competitor for the ivory tower, liberal mindset that seems to permeate every level of the AMA. Keep up God’s work, and keep writing the wonderful historic articles.

Texas Panhandle ER Doc