Estimated reading time: 13 minutes

From Hiroshima’s first operational strike to the Demon Core’s deadly lessons, this is how nukes, missteps, and raw physics still terrify a very modern world.

Why Nukes Still Keep Putin Relevant

Humanity has a weird love-hate relationship with nuclear weapons. They are at once everywhere and nowhere. The spectre of nuclear war shapes geopolitics unlike anything else. However, nobody really knows what that would look like.

The Trump Card

Nukes are the only reason anybody on Planet Earth still takes Vladimir Putin seriously. Russia has a population of around 146 million. Russia’s gross domestic product falls just behind that of Italy and just ahead of that of Canada. Germany’s economy is twice as vibrant as that of the Russian Federation. Ours is ten times larger. Were it not for the 4,309 operational nuclear warheads that Putin maintains, Russia would be rightfully viewed as a Third World backwater goat-spit of a nation. Absent those nukes, the world would have long ago banded together and spanked the Russians right out of Ukraine. However, nuclear war scares absolutely everybody, and for good reason.

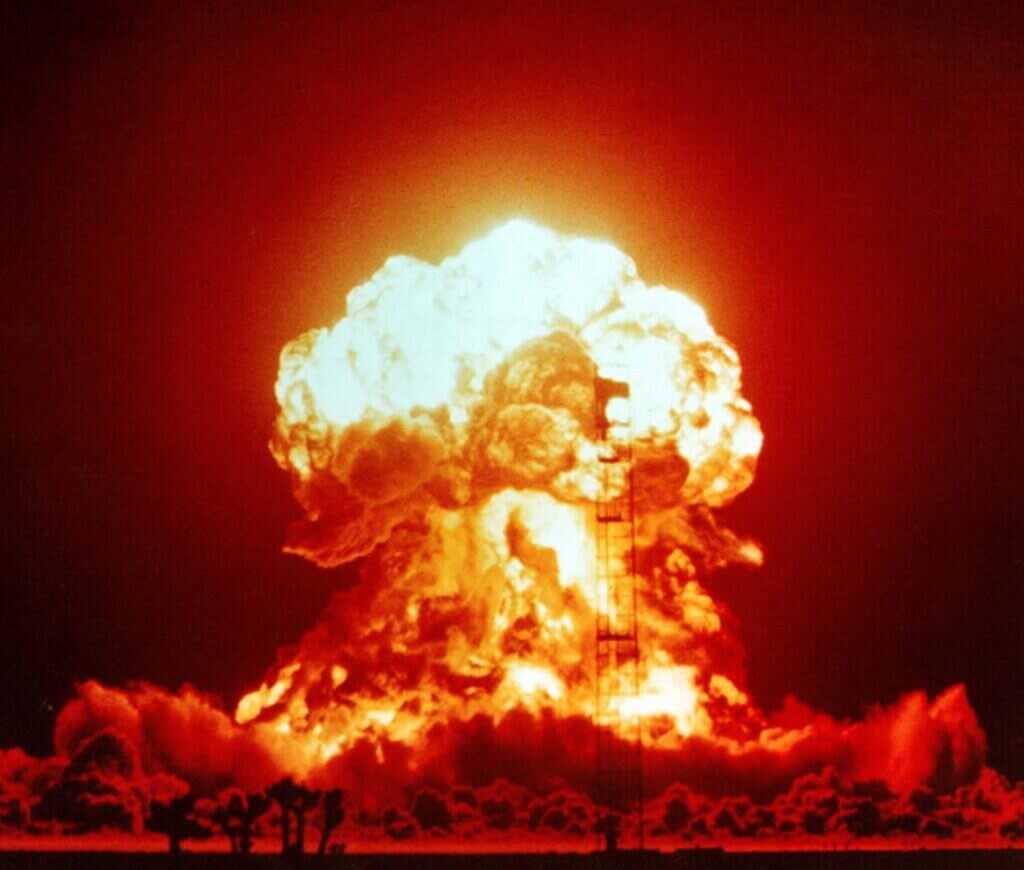

Nuclear weapons have only been used twice in real combat, and that was back in 1945. Both of those bombs were essentially prototypes. North Korea conducted the world’s last live nuclear test in 2017. Imagine how much the world has changed since 1945. Back then, telephones were the size of shoeboxes and were tethered to the wall. Now they are smaller than a box of wooden matches, ride in your pocket, and will let you talk to people in Norway from a subway in Istanbul. Nuclear weapons evolved just as transformationally; it is simply that nobody tries them out anymore.

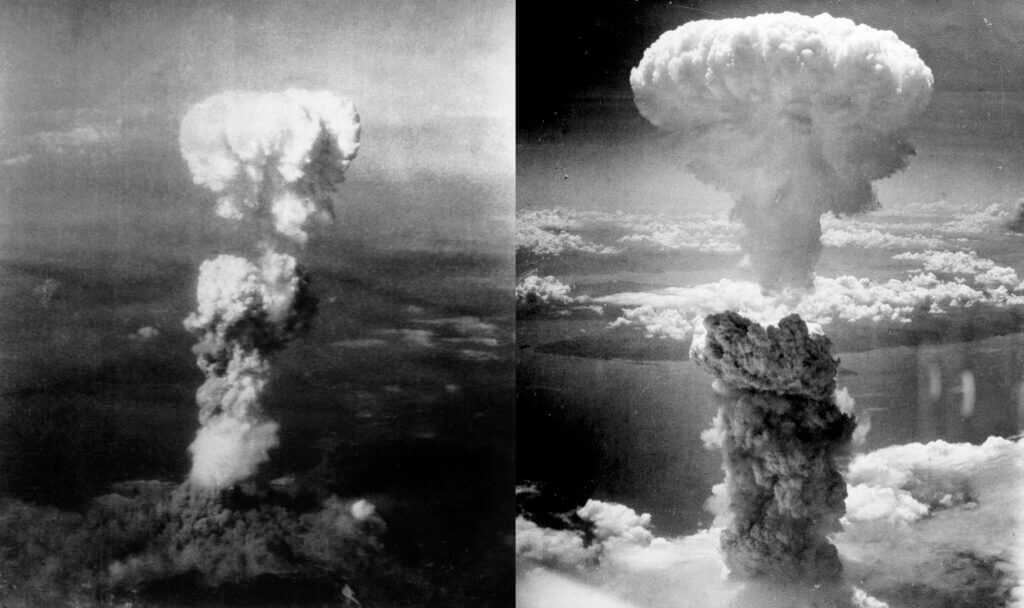

Hiroshima: The First Operational Atomic Strike

On 6 November 1945, we dropped the world’s first operational nuclear weapon on Hiroshima, Japan. The Hiroshima bomb was a gun-type design powered by uranium-235. In this case, a slug of uranium was fired along a short barrel to impact a target made from the same stuff.

This violent kinetic reaction created a critical mass that resulted in a nuclear detonation. The Hiroshima bomb had a nominal yield equivalent to around 15,000 tons of conventional TNT explosive. It killed 70,000 people at the time of detonation and claimed about the same number later from residual effects.

Nagasaki: When Smoke Saved Kokura

Three days later, we deployed a second nuclear device over Nagasaki. Curiously, Nagasaki was not the primary target. The second atomic bomb strike was to be directed at Kokura, but thick smoke over the target spared that city. The aircraft commander, a 25-year-old Army Air Corps pilot named Charles Sweeney, made the call on the fly to switch targets to Nagasaki.

This second bomb was an altogether different design that was markedly more complicated than the first. This weapon was powered by plutonium-239. Plutonium-239 does not occur in nature. This isotope is a byproduct of the reaction that occurs when uranium-238 captures a loose neutron inside a nuclear reactor. Plutonium-239 is more easily produced than uranium-235. However, it is tougher to get plutonium-239 to go off uniformly.

The second bomb used an altogether different mechanism. A series of chemical explosive charges configured similarly to the individual components of a soccer ball were arrayed circumferentially around a plutonium core. When carefully detonated at exactly the same moment, this created an immense imploding pressure wave that drove the plutonium to critical mass and resulted in a nuclear detonation. This nuclear strike killed 74,000 people at the moment of detonation and claimed a further 70,000 souls by the end of the year.

Manhattan Project Money, Pressure, and Mistakes

The Manhattan Project was the program that created these two weapons. It cost $2 billion in 1945. That would be about $30 billion today. The Manhattan Project was the second-most expensive military undertaking of World War 2. Curiously, the most expensive was the production of the B-29 Superfortress bomber that delivered the weapons. The overall cost of the B-29 program was closer to $3 billion.

Nuclear research in 1944 and 1945 was moving at light speed. We desperately needed the A-bomb as a tool to end the war. We knew that every other major combatant nation on Planet Earth was rabid for this capability. Whoever first deployed nuclear weapons at scale would undoubtedly emerge victorious. That pressure to produce resulted in some tidy little tragedies.

How Atomic Energy Gets So Big From So Little

Nuclear energy is just crazy weird if you think about it. The laws of conservation of mass and energy posit that matter and energy can neither be created nor destroyed; they just change forms. When you strike a match, the fuel in the match doesn’t actually cease to exist. It just changes into hot gases, smoke, ash, and the like. Those laws no longer apply when it comes to nuclear reactions.

When the first bomb detonated over Hiroshima, about 0.7 grams’ worth of uranium—roughly the same weight as a small paperclip—was instantly transformed into pure energy. That uranium no longer existed within the physical universe. It had actually been turned into energy in accordance with Einstein’s E=MC2. If my math is correct, that paperclip’s worth of uranium released as much energy as two million conventional 155mm high-explosive artillery rounds all going off at one time. Wow…

The Demon Core: A Softball-Sized Killer

The thing about radioactive material is that you really don’t want to get any of it on you. The half-life for plutonium-239 is 24,110 years. That means it takes 24,110 years for half of a quantity of radioactive plutonium-239 to degrade into something less lethal. That stuff is unimaginably dangerous.

Back in 1945, we had little clue what we were doing. The eggheads who made it called this particular sphere of plutonium gallium alloy Rufus. Rufus was 8.9 cm in diameter. That’s roughly 3.5 inches. For the sake of comparison, a regulation softball is 3.8 inches across.

Plutonium is really dense. This softball-sized chunk weighed 14 pounds. As plutonium corrodes readily in the presence of oxygen, this sphere was coated with nickel to help retain its stability. Rufus eventually became known as the Demon Core.

We built this monster to power the third atomic bomb that was obviously never dropped on Japan. When Japan capitulated, the core was retained at the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico for research. One of the questions that needed to be answered was exactly how close this thing was to criticality just sitting on a table.

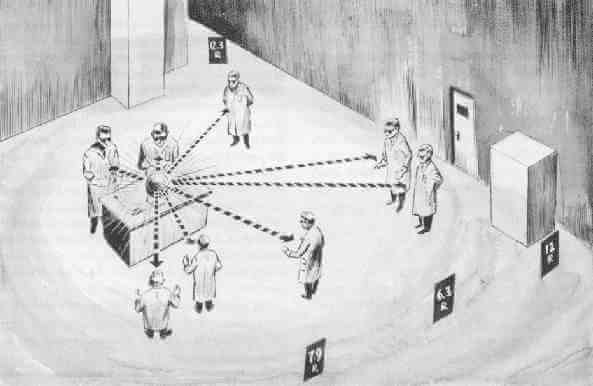

Daghlian’s Accident: A Brick, A Spark, A Fatal Dose

Plutonium naturally releases neutrons. Focusing these neutrons back into the material is what causes the mass to go supercritical and explode. How much of that neutron flux was required to get the party started was important to know. On 21 August 1945, a 24-year-old physicist named Haroutune “Harry” Krikor Daghlian was studying just that. To do so, he stacked tungsten carbide bricks circumferentially around the magic ball. Tungsten carbide is an effective neutron reflector. While he was occupied doing this, a 29-year-old military security guard named Robert Hemmerly sat at a desk some dozen feet away.

As Daghlian carefully stacked these heavy bricks around the core, he accidentally let one slip out of his hands. This thing bounced off the plutonium sphere, creating an impressive shower of sparks. He immediately moved the offending brick back to its intended spot. 25 days later, Harry Daghlian died of acute radiation syndrome. Private Hemmerly succumbed to acute myelogenous leukemia in 1978, 33 years after the accident. Hemmerly was 62 at the time.

Tickling the Dragon’s Tail: Slotin’s Fatal Slip

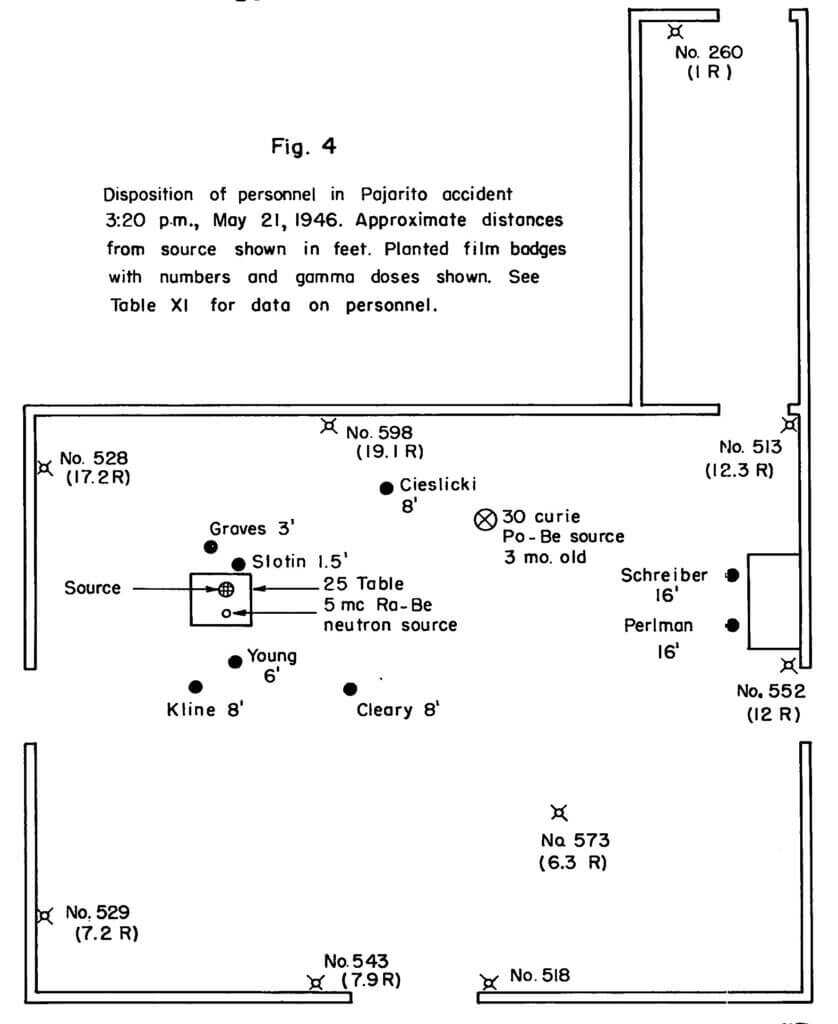

On 21 May 1946, a physicist named Louis Slotin was tending to Rufus alongside seven assistants. They were, likewise, studying the effects of neutron reflectors on critical mass. Slotin was actually scheduled to leave Los Alamos. He was only present to demonstrate the technique to Alvin Graves, another physicist who was planning to use this core during Operation Crossroads, the nuclear tests at the Bikini Atoll.

In this case, the reflectors were a matching pair of machined beryllium spheres. The astute film nerd will recall the comic reference to beryllium spheres in the epic sci-fi farce Galaxy Quest. Galaxy Quest is one of my favorite movies. If you haven’t seen it, check it out. You’ll thank me later.

Anyway, the protocol required that these spheres be arranged around the plutonium core using shims to maintain a slight separation so the mass did not become critical. However, Louis Slotin was a rebel. Arcane workplace safety rules didn’t apply to him.

Slotin had done this many times with several different cores, often while dressed in blue jeans and cowboy boots. His technique was to wedge a flat-tip screwdriver in between the beryllium spheres and twist as needed to adjust the spacing. When the esteemed nuclear physicist Enrico Fermi heard about this, he predicted that Slotin would be dead within a year. A colleague named Richard Feynman referred to this unorthodox technique as “Tickling the dragon’s tail.”

As he lowered the top sphere, Slotin’s screwdriver slipped. The two spheres were in contact for less than a second before Slotin flipped the top half onto the floor. Slotin was crouching over the apparatus at the time, so his body shielded most of the rest of his team from the explosive neutron burst.

Slotin was 35 at the time. He died of acute radiation poisoning nine days later. Of the remaining six people present, Marion Cieslicki succumbed to acute myelocytic leukemia 19 years after the accident in 1965. Surprisingly, the rest all died of fairly reasonable causes.

What A Real Nuclear Exchange Might Mean Today

The Hiroshima bomb had a nominal output of 15,000 tons of TNT. The Russian Tsar Bomba, the largest nuclear weapon ever detonated, was 3,000 times more powerful. The W88 warhead that currently rides atop modern American nuclear missiles produces 475 kilotons of explosive force, roughly 32 times that of the Hiroshima bomb.

I read recently that somebody believed that the US would return to its current GDP roughly a decade after a global nuclear exchange. Other really smart folks think a serious nuclear war would end all life on Planet Earth. Personally, I’d just as soon we not answer that question any time soon.

Thank you Dr. Dabbs. Another excellent article most informative thought provoking and insightful.

The real truth about the U.S. dropping the Atomic bombs has never been taught in our schools but it should be.

Japan went to the Russians and told them to contact the Americans and tell them they wanted to surrender.

The U.S. had broken the Japanese Military and Diplomatic codes and was already aware that Japan wanted to surrender.

Truman who was a great racist and when he was a Senator had passed legislation effectively cutting off immigration to the U.S. from Eastern Europe and Truman especially hated Asian people who he believed were sub-human. Sound familiar, the Nazi’s beleived the same thing.

Truman wanted to terrorize the Russians and stop them from an all out invasion of Japan as U.S. businessmen wanted full access to Japan’s Economy after the war. The Russians had already invaded several outlying Japanese Islands where they remain to this very day.

Truman had spent the equivalent of billions of tax dollars developing the bomb and not to have used it would have been a political liability in his run for reelection.

General Douglas MaCarthur told Truman that killing the Japanese Emperor was completely “off the table” because it would result in guerrilla warfare for decades to come and make an occupation of Japan economically and militarily impossible.

An invasion of Japan was not necessary even if the Japanese would not have surrendered immediately because Japan did not produce enough domestic food to even feed itself. In fact the majority of rice consumption came from imports from Vietnam. This is also one of the major real reasons France and later the U.S. invaded Vietnam but that is another long and sordid story of greed monger Colonialism.

In conclusion the dropping of the Atomic Bombs was “not” done to save American lives that is the “big lie” the U.S. used to justify the most horrific act of genocide ever committed against mankind. It frightened and continues to frighten the world’s population even more than the Holocaust does even the the Holocaust killed more people.

The Far Right continues to avoid the truth about the Bombs just as Japan sweeps under the rug the “Rape of Nanking” proving the Far Right in all countries are more an enemy of their own people more than any foreign government ever could be.

Stephen Hawking predicted it is highly likely the world will be destroyed in a Nuclear Holocaust.

“The Far Right continues to avoid the truth about the Bombs just as Japan sweeps under the rug the “Rape of Nanking” proving the Far Right in all countries are more an enemy of their own people more than any foreign government ever could be.”-dacian

You were doing so well until the above statement and then you managed to derail. How does the mass rape of the Chinese by the Imperial Japanese Army fit in with your statement unless you believe that all Asians the same people? If so, you just cited how General Douglass, an expert on Japan, warned that the killing of Japan’s Emperor would make the conquered nation harder to control. Sounds like before Nationalism; there was tribalism in Japan and elsewhere. Asians and Europeans both have a long sanguinary history of social and conventional warfare.

I’m an Irish Celt and there was a time when we were not considered “White” even though our traditional homeland is further west than most European Nations. When Truman starting out as a mere haberdasher trying to gain political prominence, he aligned himself with an Irish KC Democrat machine leader Tom Pendergast, but he did not care for the Irish or Catholics. The same contempt could be found with FDR and his lesbian wife, DDE and his drunkard wife. Even MLK Jr. like MLK Sn. had nothing nice to say about Catholics. This seems like the human condition.

Did you know that both Hiroshima and Nagasaki were the centers of Catholicism in Japan and were full of people as the two cities were speared from air raids until the atomic bombings? Very likely, Truman and his Masonic cohorts did NOT like Catholics including the ones in Japan. The world is mostly gray areas, and you are trying to apply some loosely related facts to try and make a weak point on your perceived virtues of leftism. You failed again, dacian.