The 1873 is a classic design, pioneered by Winchester at its birth and offered as a high-quality reproduction today by Uberti. It gives modern-day cowboy enthusiasts a chance to have a shootable version of this revered design.

For more information, visit https://www.uberti.com/1873-rifle-and-carbine.

To purchase on GunsAmerica.com, click this link: https://www.gunsamerica.com/Search.aspx?T=uberti%201873%20rifle.

It has been called, “The gun that won the West.” It has also been the title star of a motion picture. Cussed and discussed, this rifle has been the subject matter over countless campfires, hunting camps and saloons. At once praised as being one of the slickest lever actions, it is equally disdained as a weak rifle incapable of handling cartridges with enough power to knock off a mouse. Nonetheless, the Model 1873 Winchester remains an iconic rifle of the American West some 143 years after its debut.

The heart of the 1873 design is its toggle-link action located inside the receiver. Note the top-ejection port and sliding dustcover.

The ’73 was the culmination of a 25-year evolution of the lever-action repeating rifle. Beginning with Walter Hunt’s Volition Repeating Rifle with a tubular magazine and a complex and relatively fragile linkage system, the rifle’s patent was purchased by Lewis Jennings a year later. Jennings improved the linkage somewhat, producing a few rifles through the firm of Robbins & Lawrence of Windsor, Vermont, until 1852. Horace Smith and Daniel Wesson bought the patent from Jennings and acquired Jennings’ shop foreman, one Benjamin Tyler Henry, to oversee further improvement and manufacturing, calling their new company the Volcanic Repeating Arms Company.

SPECS

- CHAMBERING: .44-40 WCF

- BARREL: 20 inches

- OA LENGTH: 39 inches

- WEIGHT: 7 pounds, 4 ounces

- STOCK: Walnut

- SIGHTS: Semi-buckhorn rear, blade front

- ACTION: Lever-action

- FINISH: Case color and blued

- CAPACITY: 10 rounds

- MSRP: $1,219 (starting price)

One of the first improvements was Smith’s incorporation of a copper case with a priming compound held within the folded rim of the cartridge to replace the “Rocket Ball” ammunition that was a Hunt invention. Rocket Ball ammunition held the powder charge within the hollow base of the bullet, and like all forms of so-called “caseless” ammo it has never proven to be reliable or accurate. The cartridge Smith developed became the .22 Short. The rifle and cartridge had limited success, limited by the lack of power and reliability of its ammo. Eventually, the Volcanic Repeating Arms Company produced a lever-action pistol to go with its rifle.

The sights of the 1873 are simple and straightforward, with a semi-buckhorn rear matching up to a blade front.

The largest stockholder in this fledgling firm was a shirt-maker from New Haven, Connecticut, one Oliver Fischer Winchester. Wesson left Volcanic in 1856, and Smith followed him eight months later to form the Smith & Wesson Revolver Company. Volcanic was in receivership, and Winchester—who was reputed to have a keen eye for a bargain—bought controlling interest in the company in 1857, renaming it the New Haven Arms Company. Henry remained with Winchester and continued to develop Smith’s cartridge concept on a larger, .44-caliber scale. He also led in redesigning the rifle to handle the powerful new .44 Rimfire ammunition, culminating with the 1860 Henry rifle. The rifle saw a fair amount of service with the Union army during the War Between the States.

A STAR IS BORN

When the war was over Winchester renamed the firm the Winchester Repeating Arms Company and set about improving the Henry rifle. The 1866 model featured a bronze alloy frame, an improved magazine and a walnut fore-end to protect the shooter’s off-hand from heat during firing. It retained the .44 Rimfire chambering of the Henry.

The year of 1873 saw further improvement of the design with a new steel frame with sideplates that made it easier to access the rifle’s innards for cleaning, along with a new chambering. This new cartridge had a separate “central-fire” primer with a heavier, stronger case and more powder to increase the velocity of the 200-grain bullet. Its name was the .44-40 Winchester Center Fire or as it is more commonly known, .44-40 WCF.

As the western prairies became highways for fortune-seeking settlers, the new 1873 Winchester became wildly popular. The rugged, no-nonsense rifle found itself in the hands of market hunters, in the scabbards of cowboys and under the driver’s seat of stagecoaches through the remainder of the 19th century and into the 20th. It was no target rifle. Most 1873s could barely keep five shots on a dinner plate at 100 yards, but inside that it was accurate enough to kill a deer or put down a bad guy. It made up for its lack of accuracy and long-range power by offering a higher volume of shots. During its 46-year run some 720,000 Model 1873s were produced. If that number seems small by modern standards, recall that the country’s population was only 76 million by the turn of the 20th century—about a quarter of what it is today.

Twelve years after its introduction Winchester began making the “One of One Thousand” grade of the 1873. Rifles of this grade were test-fired at the factory, and those that met a certain accuracy level were fitted with set triggers and fitted with fancy walnut stocks with checkering and engraving on the metal work. A One of One Thousand Model 1873 would have set you back $100 at the time. Regular 1873s sold for about $18 at the time. Today a rusty relic 1873 will fetch as much as $3,000, and a One of One Thousand? The sky is the limit; count on at least six figures. One of One Hundred 1873s were also made with fewer embellishments and at about 40 bucks a copy then. Like the rest, its current value will give most of us a nose bleed. Interestingly, only 136 One of One Thousand grade 1873s were made, and just eight One of One Hundred rifles left New Haven.

[one_half]

Although somewhat delicate by today’s standards, the toggle link of the 1873 was effective and smooth cycling.

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

[/one_half_last]

The last 1873 model left the New Haven factory in 1919. But during the late 1980s and ’90s a tremendous resurgence in interest in the old rifle occurred with the blossoming of cowboy action shooting. Thousands of people clamored for shootable copies of the century-plus-old rifles. Winchester—which has undergone several changes and reorganizations over the years—has been at once blessed with products that were superior to its competition in many ways, as well as being cursed with business sense and practices that have undermined it at times. The company largely ignored the new shooting sport for some time. There were reasons—probably good ones at the time—for this position. After all, what company wants to take a step back with its products? Most look toward the future and see improvements in both design and manufacturing. But this is the gun industry, and its customer base is different than with most products. Gunners tend to be very traditional and hold strong emotional ties to their firearms. And, while Winchester does offer a line of 1873 rifles today, it certainly had gotten behind the curve in these preceding decades.

RECREATING A CLASSIC

The author exclusively runs handloaded black power loads through his Uberti 1873. Not because he has to, but because he likes to.

Several gunmakers from Europe stepped in during this time and have been making replicas of the Model 1873, as well as many other 19th century firearms. These replicas tend to be pretty authentic and of excellent quality. As such, they have become wildly popular in the cowboy action circuit. I have a couple of them and shoot them regularly. In fact, my pride and joy is my Uberti 1873 Short Rifle.

Chambered in the original .44-40 WCF, this copy of the famous Winchester is without a doubt the slickest lever-action rifle I own—and that includes a couple of century-plus-old Winchesters. The best part? It came that way from the factory.

Aside from Uberti’s superb execution, the reason that a ’73 is so slick is inherent in its design. The toggle-link lock-up is by its nature a soft and easy-to-operate design. Note how slick most P08 Lugers are (which feature their own toggle-link locking system). And while the 1873’s over-center toggle is often derided for its weakness, it is certainly strong enough for the cartridges for which this rifle was designed. If you want a more powerful rifle, buy a larger one or one of later design that was meant for a powerhouse cartridge.

My ’73 was intended primarily as a cowboy action rifle and as a companion piece to my matched pair of Colt Single Action Army revolvers also chambered in .44-40 WCF. As such, and because I enjoy shooting traditional cartridges and loads, I shoot nothing but real black powder in them. Neither rifle or revolvers have seen a smokeless powder load or a jacketed bullet.

My ’73 was intended primarily as a cowboy action rifle and as a companion piece to my matched pair of Colt Single Action Army revolvers also chambered in .44-40 WCF. As such, and because I enjoy shooting traditional cartridges and loads, I shoot nothing but real black powder in them. Neither rifle or revolvers have seen a smokeless powder load or a jacketed bullet.

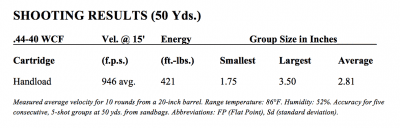

Because the Starline cases I use are a modern, solid-head type, it is physically impossible to get 40 grains of FF black powder in them. Thirty-three grains is about max, and I usually drop it to an even 30 grains since all I am doing with these guns is ringing steel at no more than 25 yards. I do keep a supply of full-power loads on hand in case I choose to hunt with these guns. With a 212-grain Lyman 427666, flat-point bullet, the Uberti kicks them out at just shy of 1,000 feet per second. It busts bunnies nicely and is accurate enough for consistent 20-yard head shots.

The 1873 is no tackdriver, but within the context of the design and its cartridge, it can be a quite effective performer.

And lest you think that cleaning black powder is too much of a hassle, I can tell you that I can get the rifle, the pair of Colts and the double-barreled shotgun cleaned, oiled and in the safe in the time it takes to clean one modern center-fire rifle or handgun loaded to the max with jacketed bullets.

The 1873, whether the original Winchester or the present-day Uberti, were never intended to be a target rifle. Groups at 50 yards are often just shy of 3 inches, and at 100 yards 10 inches are typical. But target-grade accuracy was not a criterion in 1873. Its intent was to provide better accuracy and hitting power than could be had from a six-gun for frontiersmen, cowboys and settlers. No, it’s not a buffalo, elk or even much of a deer gun. If that is your desire, you need a bigger gun. However, if your need was a fast-firing, reliable rifle capable of knocking down a man or turning a raiding party, the ol’ 1873 was a fine and much-desired piece of equipment when you were “way out west” and on your own.

For more information, visit https://www.uberti.com/1873-rifle-and-carbine.

To purchase on GunsAmerica.com, click this link: https://www.gunsamerica.com/Search.aspx?T=uberti%201873%20rifle.

Most of the article is pretty good. However, having shot .44 WCF (.44-40 Win.) since the late ‘60s, the comments about poor accuracy are hogwash, to be polite! All of my original, recent Winchester production, and Uberti replicas, will all shoot into 4” or less at 100 yards. In fact, I just returned from a trip to the Tucson Rifle Club’s range, where I made consistent hits on my 200 yard gong, from both supported and standing, off-hand positions. It seems like someone didn’t bother to do much testing, or even research before writing this article. Casts suspicion on the reliability and legitimacy of articles by this publication. You can do better!

Not much of a deer gun? Are you serious? Any idea how many hundreds of thousands… if not millions of deer (and larger critters) have fallen to the .44-40 since 1873?

BTW, Uberti chambers the same “weak” toggle link rifle in .357 Magnum and .44 Magnum, so your “full power” loads you give data for

( that don’t even come close to the original 1873 black powder load of a 200gr bullet @ 1245fps [upped to 1300fps in 1875]) can be bumped up a bit for those bullet-proof whitetails in your area.

Millions of deer taken with a 44-40? I’d scale that number back. 50k might even be a stretch. You’re using data from today in your estimations. In the era of the 1873, deer were nowhere as plentiful as today. In fact, in many populated states where deer hunting is popular today, there were NO deer in that era. OH, IN, IL, etc had no deer hunting. Around 1890 there were estimated to be around 300k deer in the entirety of the US. During that era men also were more atune to the actual needs of the family and were not so inclined to spend 40% of the family budget on deer hunting and related toys as today. 44-40 wasn’t the only caliber to be had, and to be frank you needed to be fairly minted back then to even own an 1873 Winchester.

For the price I will stick with my Henry BigBoy. Besides the better action, I can load my 44 ammo into my handgun without having to stock more calibers. And MADE IN AMERICA!

I was one of the lucky few to gain access to one of the initial few (250 pieces) Hex barreled rifles that were produced by WINCHESTER for the 2015 SHOT Show. Chambered in 44-40WCF, it will print a nice 1-1/2″ target at 25 yards. I loaded 2,500 rounds using a combination of Starline and Winchester cases with hard-cast #2 lead, and have also cycled a few jacketed hollow point factory loads. It doesn’t matter which bullet size I use (.427 .428 .430), they all perform the same. It is drop dead gorgeous and the key-stone of my rifle collection!

A notable historic firearm, and Uberti makes beautiful copies. Personally, I prefer JMB’s stronger action, and so opted for a Winchester Model 92 when I purchased one recently (a newer Miroku). (As an aside, the manufacturer’s owner’s guide specifically states that the rifle is not intended for use with black powder, though I have no clue why.)

I bought in the mid 1970’s a 1873 Winchester rifle in 44 WCF (AKA) 44/40 made in 1905.It was refinished but done right.The bore of the 24 inch octagon barrel was a little rough but it grouped good enough. I just wanted a real cowboy rifle. Never shot anything but paper or tin cans with it. One thing not mentioned was John Marlin’s input in the Winchester Rifle Company.Who later patented the side eject lever action.Then formed MARLIN RIFLE Company in 1870. I will ad that the MAXIM machine gun was a spin off the Henry /1873 lever action design.The 1873 was one of the worlds most important weapon designs impacting the future of firearms.