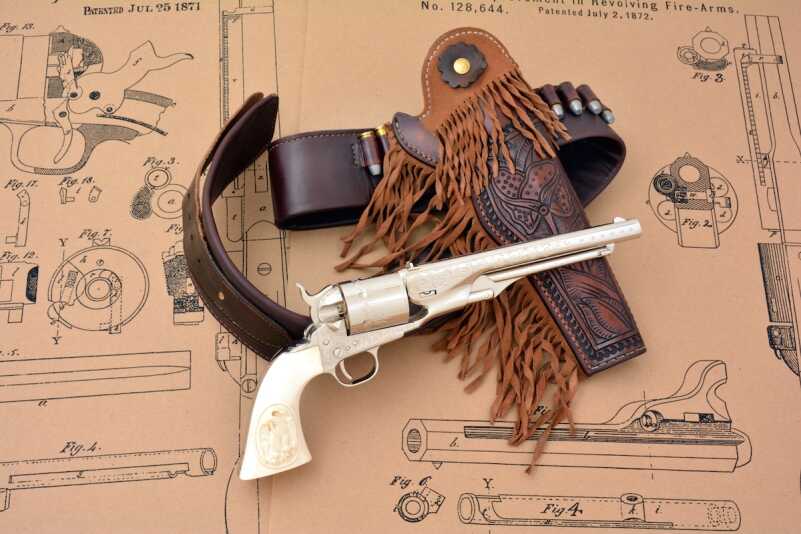

Against the background of the Richard and Richards-Mason patents for conversion revolvers, this beautifully engraved, nickel plated Long Cylinder model is a handcrafted reproduction done by R.L. Millington using a 2nd Generation Colt 1860 Army.

For more information on the Cimarron Richards Type II 1860 Cartridge Conversion revolver, click this link: https://www.cimarron-firearms.com/products/revolvers/conversion-revolvers/1860-conversions/1860-conversions-1860-richards-type-ii.html.

To purchase an 1860 cartridge conversion revolver on GunsAmerica.com, click this link: https://www.gunsamerica.com/Search.aspx?T=1860%20conversion.

The immediate advantages of a cartridge conversion revolver became apparent to anyone on the receiving end when it came time to reload.

The first years after the end of the Civil War were tumultuous as the South reeled from its losses and the Union struggled with the troubled presidency of Andrew Johnson, who had been elected as Abraham Lincoln’s vice president in 1864. A Southern congressman and former governor of Tennessee, Johnson became the 17th U.S. President taking office just a month after Lincoln took the oath of office in March to begin his second term. With Lincoln’s assassination on April 14, Johnson was thrust into the midst of conspiracies surrounding the murder and the beginning of Reconstruction. His one-term presidency was fraught with contention from Radical Republicans and ended with Johnson becoming the first U.S. President to be impeached; through he remained in office until the election of Ulysses S. Grant, who took office in March 1869.

Grant, who was a military man with no political background, stepped into the Oval Office facing a still divided nation. He endeavored to heal the rifts between North and South, while pressing for the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad at the beginning of the postwar Western Expansion, in the belief it would help unite the country. Here, in the midst of Reconstruction, there was another revolution taking place, this one in the firearms world, as American armsmakers struggled with the postwar economy and a glut of wartime arms pouring into the open market. Many small manufacturers were driven to ruin, others caught up in patent infringement suits that had begun with Samuel Colt in the 1850s, and ended in 1869 with Smith & Wesson. During the war General Ulysses S. Grant had not been a fan of S&W, which through its patents had kept U.S. armsmakers from manufacturing breech loading cartridge revolvers throughout the War Between the States, even though S&W was only manufacturing small .22 short and .32 rimfire caliber pocket pistols, (the latter a favorite backup gun for Union soldiers). In 1865, the Colt’s Patent Fire-Arms Manufacturing Co. found itself struggling with an inventory of cap-and-ball guns that were fast becoming obsolete, and unable to legally manufacture a cartridge loading revolver or conversion until the Smith & Wesson Rollin White Patent for the bored through cylinder expired in 1869. Since 1857, S&W had litigated almost every U.S. manufacturer of breech loading cartridge revolvers out of business for patent infringement or forced them to pay a royalty and stamp their guns as manufactured under license from Smith & Wesson, as well as bearing the Rollin White patent.

A comparison between a Long Cylinder conversion and an 1860 Army percussion model reveals the minor, yet efficient changes made to convert the cap-and-ball guns to metallic cartridges. Aside from modification to the hammer, a change in cylinders, and scooping out the right recoil shield, the 1860 Army retains its original appearance.

In 1868, White and S&W tried for a patent extension, just as Samuel Colt had done in 1850, successfully extending the strangle hold Colt had on the manufacturing of revolvers for another seven years. Ironically, White’s application for a patent extension was summarily denied by the U.S. Commissioner of Patents. White then appealed to Congress, which drafted a Bill (S-273) “An act for the relief of Rollin White” that passed both houses but was retuned unsigned by President Ulysses S. Grant. White’s failure to get an extension opened the door for the development of breech-loading revolvers in the U.S. But it was too little, too late for Colt’s, which would not introduce a breech loading cartridge conversion revolver until 1871, while S&W would start marketing America’s first large-caliber cartridge revolver, the .44 S&W Model Number 3, in 1870, nearly three years before Colt came to market with Peacemaker.

Colt’s had experimented with cartridge conversions while the White patent was still in effect. Pictured is a very rare Third Model Dragoon (in the 12300 or 12400 serial number range) converted to fire .44 Thuer centerfire. Note the fine donut style scroll engraving with panel scene on the barrel lug. The gun at the bottom was a factory experimental conversion No. 15703, chambered for .44 caliber rimfire.

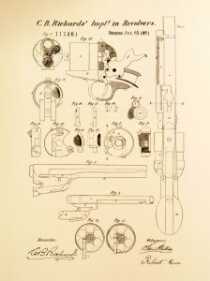

The C.B. Richards patent dated Jul 25 1871 was Colt’s first “patented” design for converting the 1860 Army to a breech loading cartridge firing revolver.

Behind Closed Doors

Although it was the largest armsmaker in America, the Colt’s Patent Fire-Arms Manufacturing Co. had wisely chosen not to butt heads with S&W, at least not publicly. Behind closed doors during the last years of the White patent, a number of experimental approaches had been taken at Colt’s to convert percussion guns to fire metallic cartridges, including one idea that simplified the process to the lowest common denominator. This was known as the “Long Cylinder” conversion, which simply did away with the percussion cylinder, replacing it with a longer, bored through cylinder, channeling the recoil shield on the right side to allow loading and manual ejection of spent shell cases, and fitting the face of the hammer with a firing pin. One might regard it as a simpler version of the Colt 1871-72 Open Top, the first cartridge gun to come from Hartford. The question about the Long Cylinder conversion, is did Colt ever build it using an 1860 Army? The only known experimental models were done using Third Model Dragoons. According to the late R. Bruce McDowell, a pioneering researcher in the history of the Long Cylinder Colt conversions, the design approach dealt strictly with making the 1860 Army suitable to fire metallic cartridges, and there are no known examples of a Colt workroom built Long Cylinder model.

Making a Long Cylinder Conversion

In creating the Long Cylinder 1860 Army conversions the original percussion hammers were reused with their noses machined to form an offset rimfire firing pin on the left of the hammer face. The original guns were designed to fire .44 rimfire, then the most widespread metallic cartridge in use. The short-lived Colt 1871-72 Open Tops, based off the 1860 Army frame, were also chambered in .44 rimfire.

Long Cylinder conversions typically retained their percussion loading lever, plunger, and latch, though they no longer served any purpose. Both three-screw and four-screw Army frames were used in making Long Cylinder models and there are design changes among known examples, which accounts for four variations.

Among alterations was the addition of a barrel-mounted rear sight dovetailed in approximately 3/16th of an inch in front of the forcing cone, or at the very end of the barrel address. Some examples, but not all, have a hammer stop, either welded or pinned within the hammer channel; newly manufactured long cylinders without the roll engraved battle scene; and converted cylinders with the rear section turned down to a ratchet stem, then built up with a ring welded to the cylinder (like one of the Colt’s experimental Third Model Dragoons), and re-bored to the size of the cartridge case. There are no known examples with loading gates, though at least one is known to have had a Richards Type I ejector housing fitted. Surviving examples indicate that the majority of Long Cylinder models were also nickel plated.

Simplicity vs. complexity; the Long Cylinder design (left) was the shortest route to a conversion by building a firing pin onto the hammer and cutting a hole in the recoil shield for it to pass through. The C.B. Richards patent for Colt used a completely new breech ring (right) with an internal floating firing pin. The breechring also shrouded the back of the cylinder and had a loading gate.

Considering that the Long Cylinder was a conversion in the first place, it is interesting to note that some of the guns were converted a second time when centerfire ammunition became available. On these examples the hammers were re-machined or simply replaced with a new hammer, and the hammer stop reshaped. There were also several different hammer stop designs which were machined, pinned or welded to the hammer channel. The majority of examples known have original 8-inch 1860 Army barrels, though some have been documented with barrels as short as 4-inches and with the loading levers removed.

Many known Long Cylinder conversions added a rear sight dovetailed into the barrel just behind the Colt’s barrel address. Reshaping the 1860 Army hammer did away with the percussion pistol’s hammer notch rear sight.

According to McDowell, there were several schools of thought on the origins of the Long Cylinder conversions. One theory is that the majority of the guns were built by Colt’s or outside contractors as “experimental” models for the Ordnance Department, but that is unlikely as most known experimental Colt cartridge conversions are accounted for and factory experimental models were almost always left in the white (not blued or nickel plated). Other opinions are that they were built in 1868 to compete with the early .46 caliber rimfire Remington Army conversions, which is again unlikely to be true considering S&W and Rollin White’s predilection to litigate any violations of the patent. Remington got around it by paying a $1 royalty for every cartridge conversion gun they built before the White patent expired in 1869. There are, however, two other opinions which have long been considered more likely; one, that the guns were built in the late 1860s and early 1870s in one or more gun shops or factories that had no association with Colt’s (such as B. Kittredge & Co. and Schuyler, Hartley & Graham in New York), or that they were hand built in Mexico from surplus 1860 Army parts. Considering the variations in assembly and serial numbers on many examples, and the variety of finish work from one gun to the next, this remains the most plausible source of the Long Cylinder conversions; but why Mexico? Because a great number of ex-Civil War Colts went South of the Border after 1865 and Mexican gunsmiths were a very talented lot.

McDowell came to the same conclusions writing that, “There appears to be no possibility that Colt was involved with the [manufacturing of the] Model 1860 Long Cylinder revolver, based on the following reasoning. One, the stamping dies used for the assembly numbers are larger and of a different typeface than those used by Colt on revolvers or conversions; two, though double-finger rotating arms are used on some Long Cylinder specimens, they were welded parts and welding was not practiced by Colt, and three, the mixing of serial numbers on most, but not all Long Cylinder cartridge revolvers was not a general practice of Colt. Unmatched serial numbers were only found on the U.S. Richards Conversions because of the rush to complete them for the U.S. Ordnance Department, which demonstrated no concern over numbering.”

Hammering down the variations, the percussion hammers from the 1860 were reused and cut to fire metallic cartridges (rimfire and centerfire) for Long Cylinder conversions, and machined flat in the Colt’s Richards patent design, (bottom), which used a floating firing pin inside the breech ring.

Further questions arise regarding the general quality of workmanship on many Long Cylinder models, which, according to McDowell’s research, were primarily constructed from old (obsolete) percussion revolver parts with newly fabricated cylinders and not up to Colt’s manufacturing standards.

So where did the roughly 60 known Long Cylinder Colts come from? They were not built by the Colt factory, but by various individuals between the late 1860s and 1873-1874; whether or not those individuals were in Mexico or the Border States, or New York State, remains one of the unsolved mysteries surrounding the these rare Long Cylinder Colt 1860 Army conversions.

The two examples shown are not original Long Cylinder conversions but two out of a handful of reproductions built a little over a decade ago by Colorado custom gunmaker R.L. Millington. The guns were all based on original Long Cylinder conversion designs and were done on 2nd and 3rd Generation Colt 1860 Army revolvers. The nickel plated model, in a period style seen on Colt revolvers engraved in Mexico during the 1860s and 1870s, is the only engraved, nickel plated model done by Millington. It is fitted with hand carved Mexican eagle and snake ivory grips by Dan Chesiak and Dennis Holland.

The Cimarron F.A. Co. Richards Type II 1860 Army Conversion

The closest anyone can come to getting a Colt 1860 Army conversion that is similar to those manufactured in the early 1870s, is the Richards Type II conversion sold by Cimarron F.A. Co., in Fredericksburg, Texas. The Type II is built for Cimarron by A. Uberti, and represents quite a departure from the Italian gunmaker’s tradition of building either Colt black powder reproductions or SAA models. It is based on the second model 1860 Army conversion produced from 1871-72 to the mid-1870s.

SPECS

- Chambering: .45 Colt

- Barrel: 8 inches

- Weight: 42 ounces

- Grips: One-piece walnut

- Sights: Hammer notch rear, blade front

- Action: Single-action

- Finish: Blued with case colored frame and hammer

- Capacity: 6

- MSRP: $616.20

In 1871, Colt’s assistant superintendent of the armory, Charles B. Richards, was granted patent No. 117461 for Improvements in Revolvers with the patent assigned to Colt’s and intended for the alteration of the 1860 Army to .44 caliber central fire cartridges, a process that began commercially in 1872. For Colt it was the means to an end; using up a vast inventory of 1860 Army parts left over from the war.

The Cimarron F.A. Co. Richards Type II 1860 Army conversion is as close as you can get to any of the original 1860 Army factory or field conversions. The guns are offered in .38 Special, .44 Special, .44 Colt/Russian, and .45 Colt.

The original conversion commonly referred to as the Type I or First Model, utilized a breechplate with a rebounding firing pin. The breechplate was combined with a newly manufactured cylinder or a cut and bored through cap-and-ball cylinder with a new ratchet to engage the hand. The conversion also required removing 3/16th of an inch from the face of the recoil shield into which the breechplate (also referred to as the conversion ring) was seated and secured by the cylinder arbor. The right side of the breechplate and recoil shield was channeled slightly larger than the size of the cylinder bore to facilitate the loading and ejection of cartridges from the breech end of the cylinder. On all Richards conversions this channel was protected by a hinged loading gate attached to the breech ring. The final alteration to the 1860 required the hammer face to be ground flat in order to strike the floating firing pin in the breechring. The sum of these modifications were irreversible and thus ruled out the refitting of the gun with a percussion cylinder. The most complicated and costly component of the conversion, however, was the cartridge ejector assembly. A newly fabricated housing (containing the ejector rod, spring, and ejector head) was attached to a metal plug that slipped into the channel previously occupied by loading rammer. The lug and right side of the barrel just above the rammer channel had to be notched to accommodate the ejector, which was then secured to the gun by the screw previously used for the loading lever. It was an efficient design, but labor intensive.

The author unleashes a blast of mighty Goex .45 Colt Black Dawge from the Cimarron Richards Type II conversion.

Priced at $15.00, it is estimated that 9,000 examples were manufactured by Colt’s, a number of which were sold to the U.S. Army and martially marked. Not long after the Type I was added to the Colt line, William Mason (Colt’s superintendent of the armory and designer of the 1873 Colt Peacemaker) came up with a better idea, better meaning less expensive to build. Mason’s design provided the basis for an “interim” model, the Richards Type II. Often referred to as the Transition Richards, this second variation reduced production costs, although it retained the Type I cartridge ejector assembly. Combining the Wm. Mason cylinder and conversion ring design, the interim model saw the return of the hammer notch rear sight, a firing pin riveted to the percussion hammer, and a simpler breech ring and loading gate. The short-lived Type II depleted remaining inventory while Colt’s prepared to introduce the all-new Richards-Mason line, which would be expanded to include the 1851 Navy, 1861 Navy, and Pocket pistols beginning in 1872-73.

Deadly accurate at 25 feet, the Richards Type II and Black Dawge cartridges drilled that old X bull.

In reproducing the Richards Type II, A. Uberti craftsmen have fashioned a well balanced and smooth operating six-shooter that delivers exceptional accuracy right out of the box. I tested this gun with Goex Black Dawge .45 Colt cartridges. These heavy hitting black powder rounds are authentic to the period and produce a deep roar, a hefty kick and a billow of acrid black smoke (comes with authenticity). They’re messy alright but remarkably consistent, more so than many smokeless rounds. At 25 feet the Richards Type II landed six Black Dawges in the X Bull with five of six overlapping! As should be expected with a conversion like this, it does not shoot to point of aim (this one shot low by about three inches, which is actually pretty good). If you want to fix this you can shave down the sights, but I simply determine the point of impact and adjust my aim accordingly when I shoot these types of guns.

Weighing in at 42 ounces (empty) trigger pull measured a discreet 1.16 pounds which added to the gun’s accuracy. The Cimarron F.A. Co. Richards Type II proved more than adequate, with the feel of a true 1860 Army conversion, regardless of the cylinder’s length. All in all, it is a great opportunity to own a new version of an interesting (and very mysterious) revolver.

For more information on the Cimarron Richards Type II 1860 Cartridge Conversion revolver, click this link: https://www.cimarron-firearms.com/products/revolvers/conversion-revolvers/1860-conversions/1860-conversions-1860-richards-type-ii.html.

To purchase an 1860 cartridge conversion revolver on GunsAmerica.com, click this link: https://www.gunsamerica.com/Search.aspx?T=1860%20conversion.

Why isn’t the Richard’s Transition conversion made with the correct ejector rod? I just purchase one and it has the short ejection rod.

Was watching some old Bonanza episodes, taking place in 1866. Little Joe carried a Colt Navy, Pa carried a 1858 Remington, Hoss and Adam carried 1860 Armys, I think. They took the fore ends off of 1892 Winchesters in an attempt to make them look like iron framed Henrys.

I never noticed when I was a kid watching these shows, only recently (thanks, Utube) have I noticed these details. Someone was paying attention to some semblance of authenticity back then.

After reading this article, I’m kind of wondering if there’s a polymer-framed Richards Type II out there somewhere. Why? Authenticity!

Thanks for the article. I own two SA revolvers, a Ruger Super Blackhawk in .30 carbine and a Ubertti 1873 Cattleman in .357.

Quite attached to both of them, fine revolvers.

Also wishing I hadn’t been an idiot somewhere around 1985 and sold my Interarms Virginia Dragoon in .44 Mag, but I’m sure most have a story about the one they let go and regretted later.

Actually, the ’58 Remington is an even better choice among antique designs for conversion. Even setting the strength of its action aside, changing cylinders is much faster than for a ’60 Colt, and unless you are the Flash, even faster to reload than an SAA. Same difference with the Ruger Old Army, aside from its weight.

Great article and most informative–I am a long-time patent lawyer, and always found the juxtaposition of law, history, war, and engineering fascinating. Smith’s use of its patents to stifle competition and progress is similar to the Wright brothers’ long legal campaign against Glenn Curtiss. That legal battle over aviation control rights and mechanisms went on for decades, until finally resolved with the formation of today’s Curtiss-Wright Corporation !! The impact of the exclusive Smith revolver contract with Imperial Russia was also instrumental in allowing Colt’s subsequent domination of the Western US market. Thank you again for all of your great historical articles. DMD

Great article Dennis…I surely do miss my quarterly copy of Guns of the Old West magazine!

Very good article about a little known time period in early western firearms history. Well done.

Interesting to read how a single company held back firearms development in the middle of a major war for profits. Not that I am against patents and the free market, the middle of a war seems a bad time to make an issue out of such things, especially since S&W wasnt trying to make any weapons the army could use. Then when the patent extension was denied probably handed out a few bribes in congress to get a special exemption, and were probably shocked when a former general who resented their holding back weapons development during the war wouldnt sign it. Which does seem shocking as corrupt as Grant was said to be.

And it would be really nice if western movies were a bit more realistic. Watching westerns one would assume the colt peacemaker and winchester rifles were the only weapons available at the time. Vs the prolific and much cheaper conversion guns.

As a 35+ year armorer in the movie TV industry I can tell you first had that the authenticity level of gun used in films and TV have increased dramatically, especially in the last 25 years. I could go on and on about the incredible detail we’d go to to make the firearms correct for the period.

If you’re referring to films made in the 30s, 40s, 50s, even 60s, yes it was very common to see lever action rifles and double action revolvers used in periods when they didn’t exist. Directors wanted lots of firepower and actors many times were unable to manipulate the single actions effectively.

Mainly, the directors/writers didn’t care. There was no instant negative feedback to glaring inaccuracies like there has been via the internet to make them aware. Also the few movie armories were limited in what they could provide. There just wasn’t the selection of reproduction firearms then that there is now.

Anyway lots more to that story.

My cousins husband was in the costuming end of the movies for about 25 years in the 70’s and 80/s. He did a lot to authenticate clothing and essentials too. He is also a “Cowboy Artist” of considerable note now. He lived with the Sioux Indians for several years learning customs, clothing, and utensils that he incorporated into movies he worked on. He also did the costuming for several TV shows of note. Don’t want to name him because of his privacy, but I have some of his art work myself. He is a real “cowboy” too.

At least the spaghetti westerns were close – as they looked like the conversion type guns. I’m not sure the Italians were interested in making them look just like the original conversion guns – but at least they did look more like a Civil War cap and ball pistol, that shot cartridges.

Grant was not a corrupt person. That he died broke is proof of that. He was not very good at picking people for his administration having no previous political experience. Thus he got a lot of corrupt individuals that took advantage of him.

As far as westerns go, they have been getting better with all the replicas and sometime originals being used such as in “Crossfire Trail” where an original Winchester 1876 albeit converted to a musket model, was used. The early westerns were nearly all Colt SAAs and Winchester 1892s no matter what the time period was supposed to be. The reason was that the studios bought up these guns that were still being made right up to WWII. For most people watching a film it simply doesn’t matter. The guns look “western” and that is good enough. Really the whole western thing is a myth and was even at the time it was happening. The dime novels assured that. Watching a western is escapism. Hollywood created its own West and most people are happy with it. I mean owning an original S&W Double Action Frontier with holster I can tell you the original holster is nothing like those low slung impractical things seen on most westerns. People back in the 1880s were not ignorant of electricity and telephones as often is portrayed. Many of the larger towns had electricity but you never see it in a western except in those that are supposed to take place in the early 20th century such as the “Shootist.” Even remote places like the Montezuma Hotel in remote New Mexico had electricity in 1881. It didn’t work out that well since it burned down twice due to electrical fires before the finally got it right in 1886. It is still there now used as a school started by Prince Charles and Warren Buffet of all people.

The West of westerns is a myth. It always has been. So low slung guns, kerosene lanterns, and Winchester rifles are going to dominate.

I’m watching a western the tales of wells fargo , abe lincoln has just been shot, Dale Robertson is wearing a colt peacemaker , 1865. Just watched the seachers john wayne civil war vet wearing a colt peacemaker , red river , monty cliff just home from the war wearing a colt peacemaker ???

One of the most enjoyable and enlightening articles I have found here. I had early Ruger Old Army and it was a strong beast and extremely accurate, the only black powder gun I ever owned. Even without any desire to persue these firearms, the article was a excellent read.

Thank you,

WR