Estimated reading time: 12 minutes

Curious things happen in war. Lots of curious things happen in really big wars. As World War 2 was the most expansive conflict in human history, there was no shortage of weird stuff to be found. In 1942, a Luftwaffe pilot named Armin Faber inadvertently and singlehandedly changed the calculus of the air war over Europe.

Table of contents

Martial technology veritably exploded during the Second World War. With national survival on the line, the combatant nations threw the entirety of their intellectual and industrial might behind their respective war efforts. The end result was military evolution on an unprecedented scale.

The seeds planted during these six interminable years blossomed into things we can find around us even today. Heinz Guderian’s Blitzkrieg eventually became the combined arms warfare that we can see on the newsfeeds playing out in Ukraine. WW2 saw the genesis of such stuff as the modern combat submarine, the surface-to-surface ballistic missile, the main battle tank, the cruise missile, and the assault rifle. Silly Putty was serendipitously discovered by WW2-era researchers trying to divine a way to make synthetic rubber. In the case of aviation technology, advances in fighter design could spell the difference between victory and defeat.

All involved coveted the other’s secrets. Advances in materials science and aeronautics lent advantages that could be exploited or countered on the aerial battlefield. Discovering those secrets became a mission of strategic importance.

Available on GunsAmerica Now

The Problem

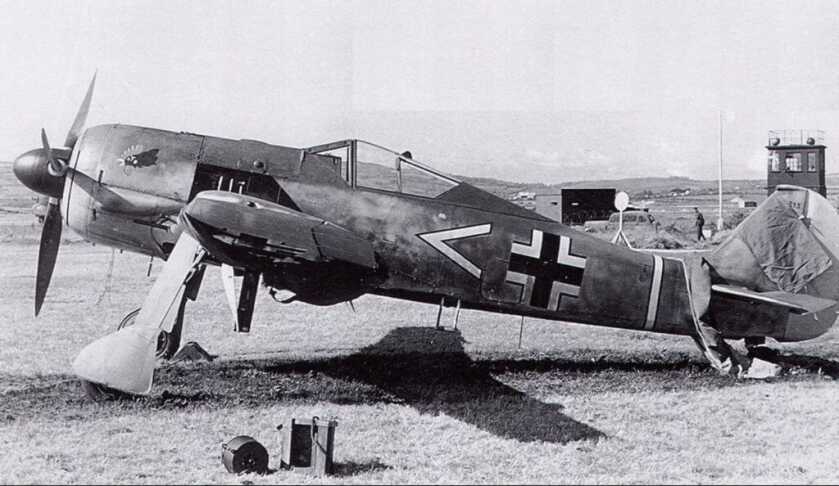

The Focke-Wulf Fw 190 was a war-changing airplane. Fast, rugged, powerful, and mean, the Fw 190 outclassed everything in the skies when it was first introduced in 1941. With the proposed invasion of the British Isles hanging in the balance, British aircraft designers and strategic leaders simply had to have one. The rub was that Herman Goering and his Luftwaffe seemed disinclined to loan a copy out. Goering had actually decreed that the new plane was not to be flown over British territory out of fear one might be captured more or less intact.

The British military leadership actually fleshed out a bold plan to launch a commando raid onto the continent along with an experienced RAF pilot who spoke German. The mission was to breach the perimeter of a Luftwaffe airfield, neutralize the guards, steal a spanking new Fw 190, and fly it back to England so the technology exploitation boys could tear it apart and have their way with it. Had this operation been green-lit, it likely would have been a bloodbath. Fortunately for the Allies, Oberleutnant Armin Faber rode to the rescue.

The Plane In Question

First flown in the summer of 1939, the Fw 190 was the brainchild of the legendary German airplane designer, Kurt Tank. Tank’s sleek fighter was powered by a BMW 801 14-cylinder air-cooled radial engine. While the Americans had extensive experience with radial engines in military aircraft, the Germans really not so much. One of the appeals to Tank’s radical design was that it did not require the coveted Daimler-Benz DB 603 inverted V-12 powerplant used on the Messerschmitt Bf 109 as well as heavy fighters like the Me 110. There were never enough DB engines to go around.

Variants

While the Messerschmitt Bf 109 was a racehorse, the Fw 190 was a cavalry mount. By the time Oberleutnant Faber was flying them, the Fw 190 A-3 model was operational. This variant featured a pair of rifle-caliber 7.92x57mm MG17s in the cowling and a brace of MG FF/Ms 20mm autocannon in the wing roots.

Of the many revolutionary design features of the Fw 190, two stand out. The Fw 190 utilized a vacuum-formed Perspex bubble canopy for superior visibility in all aspects. Additionally, the wide-track landing gear was mounted to the wings and folded inward. By contrast, that of the Bf 109 affixed to the fuselage and folded outward. The Bf 109 arrangement allowed for a thin, aerodynamically efficient wing, but the narrow track was miserable in a crosswind or while managing the plane’s prodigious engine torque.

Of 33,984 produced, hundreds of Bf 109s were lost to ground accidents as a result. The Fw 190 was much more forgiving. The Fw 190 eventually came to be known as the Butcher Bird.

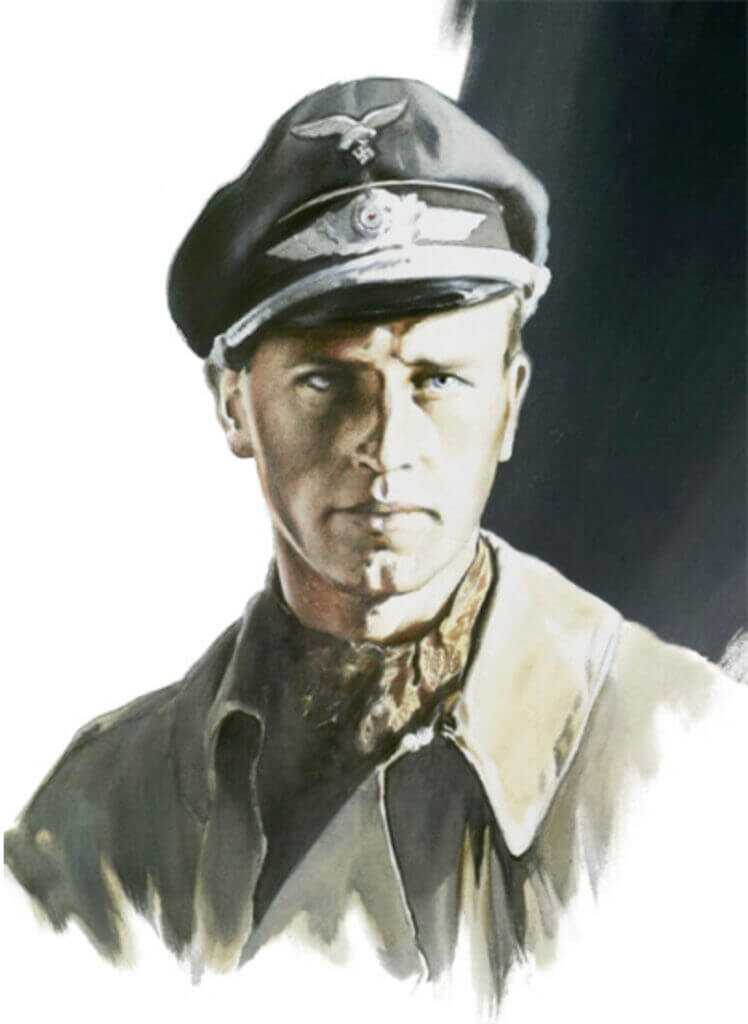

The Mission and Armin Faber

In the summer of 1942, Oberleutnant Armin Faber was a fully qualified Luftwaffe fighter pilot. However, he was assigned as Gruppen-Adjutant to the commander of III Fighter Group of Jagdeschwader 2 (JG 2–Second Fighter Wing) based at Morlaix in Brittany. In this capacity he had wide-ranging administrative responsibilities, but he still had to maintain his flight currency. On 23 June 1942, Oberleutnant Faber was granted permission to fly a combat mission with the 7th Staffel over France. The 7th Staffel was one of the few operational fighter units to be flying the brand new Fw 190.

Faber’s mission was a tough one. Half a dozen A-20 Boston medium bombers were returning from a mission over the continent. Three full RAF squadrons of Spitfires manned by Czech pilots, numbers 310, 312, and 313, were tasked to escort.

Goals

While bombers attacking strategic targets was the overt briefed mission, another tacit goal of Allied air planners was to kill German fighter pilots. The Allies had the reserves in both machines and manpower to replace downed aircraft at will and rotate experienced pilots back home to impart their wisdom to the next generation. By contrast, Luftwaffe pilots flew until they died. This ghoulish policy produced some extraordinarily high scores but was clearly not sustainable.

By way of illustration, the leading American ace, Richard Bong, had 40 victories by war’s end. Marmaduke “Pat” Pattle was the highest-scoring UK ace with somewhere between 51 and 60 kills. Russian Ivan Kozhedub shot down 60 Axis planes. By contrast, Erich Hartmann, the top-scoring Luftwaffe fighter ace, ended the war with a total of 352 kills. In June of 1942, the RAF was out to slaughter German pilots.

Danger Around The Corner

All six Boston bombers made it back to UK airspace safely. However, a roiling air battle between the German Fw 190’s and the RAF Spitfires rose over the English Channel. Before it was over, two Fw 190s and seven Spitfires were shot down. As is often the case in the frenetic mayhem of combat, Oberleutnant Faber got separated from the rest of his mates.

Flight SGT Frantisek Trejtnar got on Faber’s tail and chased him over Exeter in Devon, England. By now, Faber had only a single cannon still operational. After a desperate dogfight, Faber executed a textbook Immelmann turn and blinded Trejtnar in the sun. He rolled back to close on the Czech’s Spit head-on and shot him down with his last few remaining cannon rounds.

Trejtnar caught shrapnel in his arm but successfully egressed his crippled airplane. He did, however, break his leg upon landing. Trejtnar’s Spitfire impacted near Black Dog, Devon. Now low on fuel, Faber tried to get his bearings.

Faber Hits a Problem

The Bristol Channel is a major sea inlet separating South Wales from Southwest England. It is formed by the Severn Estuary of the Severn River and runs roughly in the same direction as the larger English Channel to the south. Faber got turned around, mistook the Bristol Channel for the English Channel, and headed out over South Wales falsely assuming it was France.

In the days before GPS and widespread electronic navigational aids, this was shockingly easy to do. Faber had obviously never flown over this terrain before. As the Bristol Channel is a huge, wide strip of water and Faber was pretty jazzed from his recent brush with death, this was an honest mistake.

Faber Caught In The Snare

In short order, Faber happened upon RAF Pembrey in Carmarthenshire in Wales. Pembrey had previously been host to an RAF armament school. In June of 1942, it was bustling, but there was little threat of air attack from the Luftwaffe. As a result, the RAF personnel stationed there were shocked to see one of the latest German fighters buzz the field and perform an aileron roll to signify victory in combat.

Faber entered the pattern, lowered his landing gear, and touched down. The duty pilot, SGT Jeffreys, directed ground crews to guide the German plane to park in the dispersal area. As Pembrey was primarily a training base, there were no small arms handy. Jeffreys therefore grabbed a flare pistol and ran up to the sleek German fighter as Faber shut down the engine. Jeffreys was on the wing and had the Very pistol in his face before Faber realized what he had done.

The Rest of the Story

Oberleutnant Faber was so despondent he attempted suicide on the spot only to have the nearby RAF personnel physically prevent him. He was subsequently transferred to RAF Fairwood Common for interrogation. His personal escort was Group Captain David Atcherly who had, by now, scared up a revolver. Concerned that the German pilot might attempt to escape, Atcherly kept his Webley aimed at his prisoner the entire journey. At one point the truck hit a pothole and the pistol discharged, narrowly missing the hapless Luftwaffe flyer. Armin Faber’s was clearly a pretty epically sucky day.

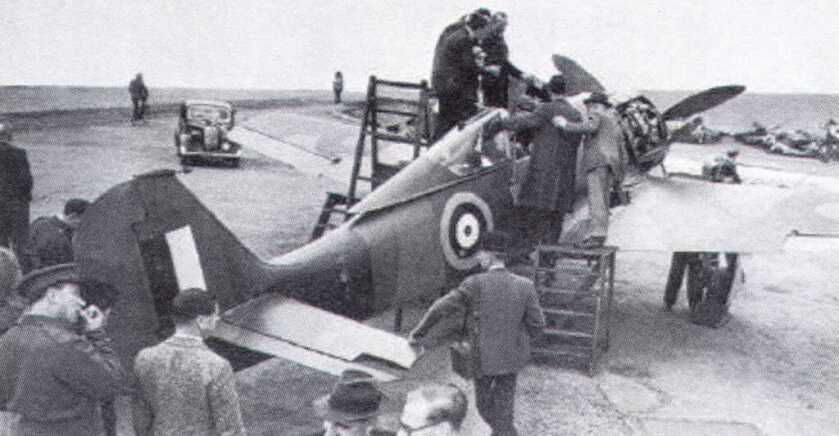

A Captured Fighter

The Allies pored over every inch of the captured fighter. Faber’s machine was the only fighter version of the Fw 190 captured by the Allies intact during the war. They assigned it serial number MP449 and repainted it in RAF colors. The RAF Establishment at Farnborough flew the plane for nine hours discovering its engineering secrets before transferring it to RAF Duxford for a tactical assessment. MP449 flew against the new Mk IX Spitfire in mock combat evaluations. Eventually, the engine was removed for study. Having learned all they could, MP499 was scrapped in September of 1943.

READ MORE: Robert Johnson and his Indestructible Thunderbolt

Oberleutnant Faber was sent to a POW camp in Canada. While there he escaped twice but was captured in short order. Canada is a big country, and the Atlantic is a sizable ocean. The chances of his escaping and evading back to Germany were fairly remote. He was compassionately repatriated back to Germany prior to the end of the war due to medical issues. Despite a lot of Googling, I couldn’t ascertain those details.

The instrument panel and sundry cockpit parts of Faber’s Fw 190 were eventually put on display at the Shoreham Air Museum in Kent, England, alongside salvaged components from Trejtnar’s Spitfire. Armin Faber ultimately survived the war. In 1991 he visited the Shoreham Museum and donated his Luftwaffe pilot’s wings and ceremonial dagger to the display. Faber’s contribution to ultimate Allied victory, while entirely unintentional, was fairly profound.

*** Buy and Sell on GunsAmerica! ***

Just finished a real good book, Thunderbolt by Robert S. Johnson and he vividly describes his dog fights against both Fw 190’s and Bf 109’s.

I’m surprised the Oberleutnant was not shot upon arrival back in Germany. The gun camera footage must have been embarrassing to the Flight SGT.

I’m surprised Oberleutnant Faber was not shot upon arrival back in Germany. An interesting story. I’m sure the Flight Sgt. was embarrassed

when the gun cameras were reviewed.

Haven’t heard from you in a while doc. As always, your pen never disappoints!

Love those historical accidents. Great story Dr. Dabbs.