The Twilight Zone ran for five years starting in 1959. Shot entirely in black and white with fairly rudimentary special effects, The Twilight Zone was a great example of what can be accomplished in a TV medium with limited resources and some truly superlative writing. The Twilight Zone orbited around the genres of black comedy, drama, absurdism, horror, and science fiction.

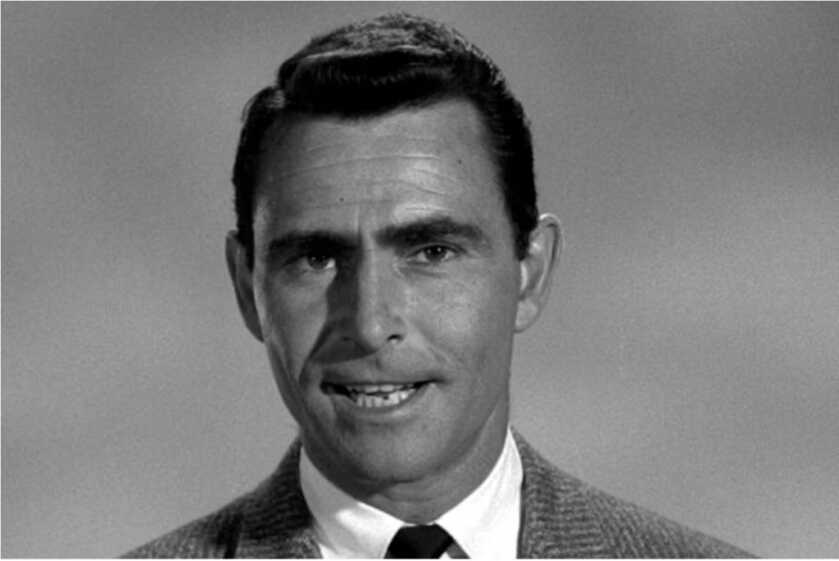

The Twilight Zone really did make you think. It was deep, cerebral, and at times genuinely horrifying. Like most truly revolutionary artistic endeavors, The Twilight Zone was the product of a singularly creative mind. Rod Serling, the true father of The Twilight Zone, was a remarkable man indeed.

The Guy

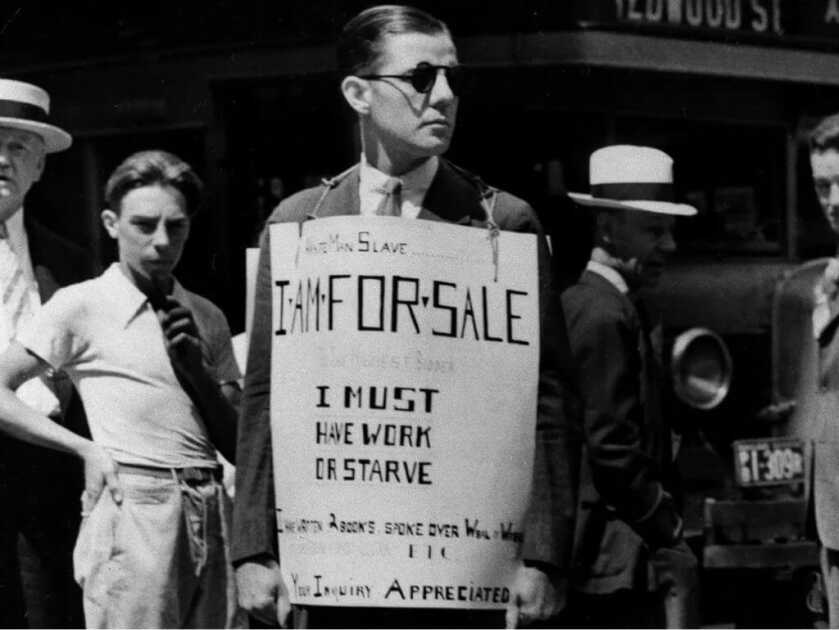

Rodman Edward Serling was the second of two sons born to Jewish parents in 1924, in Syracuse, New York. His father had been an amateur inventor until the kids showed up and he had to find honest work as a grocer and butcher. The patriarch lost his job in the Great Depression and did what it took to scrape by just like everybody else.

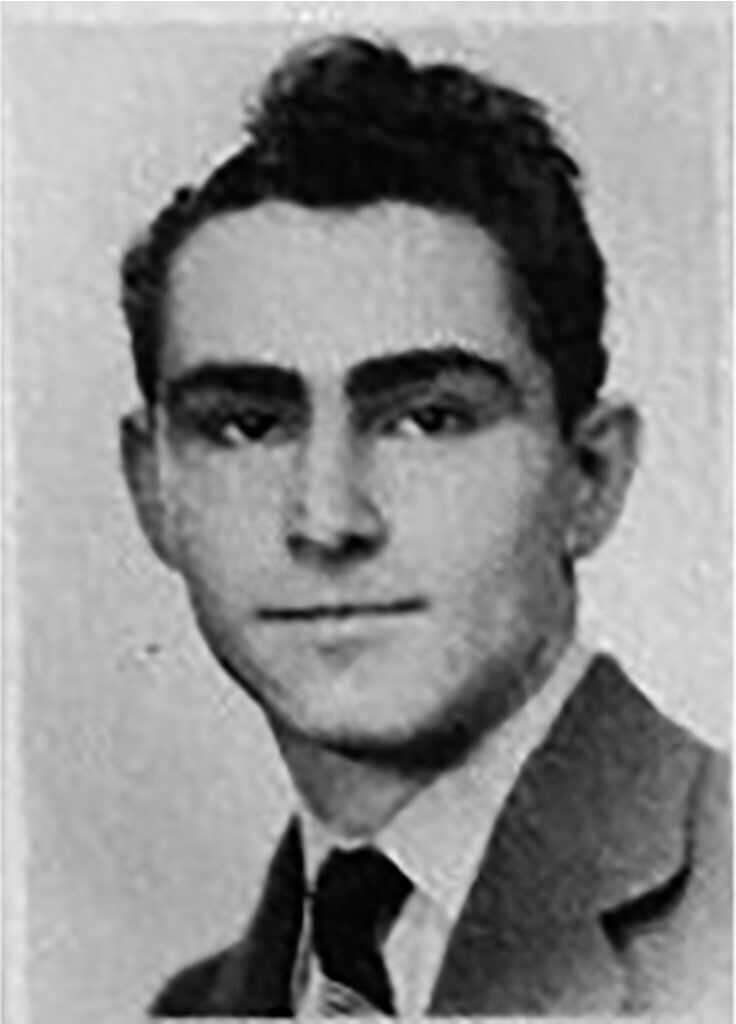

Young Rod was a born performer and the class clown. He enjoyed public speaking and excelled in debate. While in High School he was competitive at both tennis and ping pong. Serling tried out for the football team but was told that, at five foot four, he was much too small.

Serling was editor of his school newspaper and used this venue to advance various social causes including support for the brewing war against the Axis. He was accepted to college in his senior year but turned it down to enlist in the Army. Only vehement intervention by his Civics teacher convinced the boy to wait until graduation. Rod Serling was rabid to serve his country.

Going to War

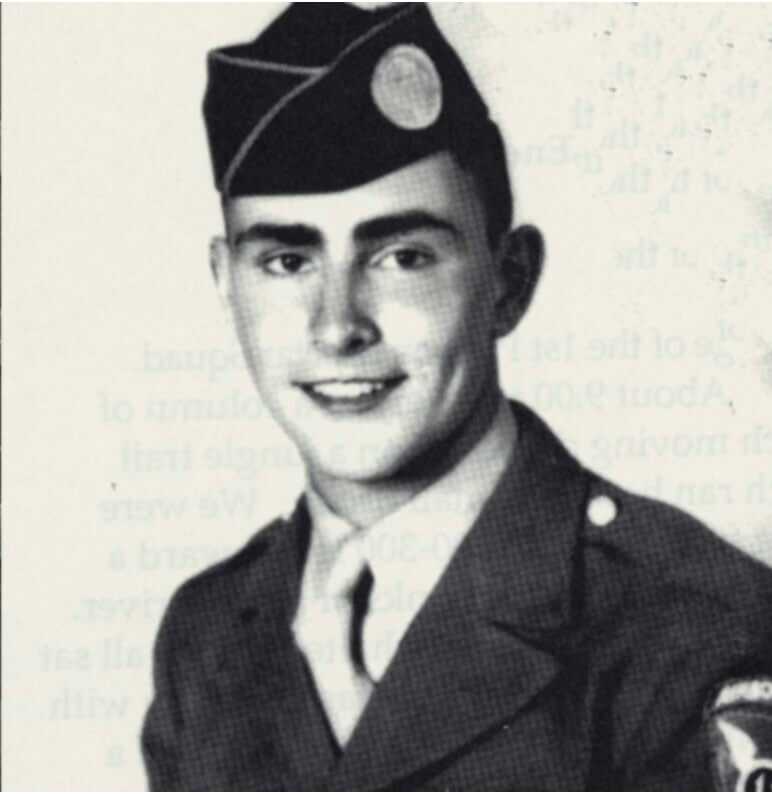

Rod Serling fancied himself airborne material and volunteered for the paratroops. He was initially told he was too small but simply would not take no for an answer. In 1943 he found himself at Camp Toccoa, Georgia, serving under Colonel Orin “Hard Rock” Haugen. He was later assigned to the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 11th Airborne Division—“The Angels.”

Serling had a lot of nervous energy. The stresses of combat training did not make that better. As an outlet to vent his aggression this diminutive kid threw himself into boxing. He competed in seventeen bouts as a flyweight. Observers described him as an absolute berserker in the ring. He attempted to compete in Golden Gloves as well. Before being simply beaten down, he had his nose broken twice.

As a Jew, Serling had hoped to go to Europe to fight the Nazis. However, fate sent him west instead. He first saw action in the invasion of the Philippines. In this fight, the 11th Airborne did not conduct widespread parachute assaults but was rather used as elite infantry. In short order, Serling and his mates were in a desperate fight to the death with the Japanese on the island of Leyte.

Serling could be caustic, and at some point, he rubbed somebody important the wrong way. This earned him a posting to the 511th Demolition Platoon. This hardscrabble mob was called the “Suicide Squad” in recognition of its astronomical casualty rate in combat. Sergeant Frank Lewis, his Platoon Sergeant, had this to say of him, “He screwed up somewhere along the line. Apparently, he got on someone’s nerves…he didn’t have the wits or aggressiveness required for combat.”

Lewis observed that when Serling and others were trapped in a foxhole during a firefight waiting for darkness, he noticed that Serling had not reloaded any of his extra carbine magazines. The diminutive paratrooper often inexplicably went exploring on his own against orders and got lost. In this horrible place at this horrible time, given such gross inattention to security, it is amazing the man survived.

The horrors of jungle combat changed this young kid from New York and went on to shape his career as a writer. While operating in the mountainous regions of Leyte, the only means of resupply was by air. At one point a fellow Jewish soldier named Melvin Levy was entertaining his mates with an improvised comic monologue while they caught some shade underneath a palm tree. At that very moment, a crate of food airdropped from an American cargo plane unexpectedly decapitated his friend. His buddy Serling subsequently led the man’s funeral service and placed the Star of David atop his grave.

While liberating Luzon, Serling and his fellow Demo men were tasked to destroy innumerable concealed pillboxes and similar fixed fortifications. At one point Serling entered a supposedly abandoned blockhouse only to find a Japanese soldier waiting with a rifle. Before either man could react, one of Serling’s fellow paratroopers shot and killed the enemy soldier.

Along the way, Serling was wounded twice, once in the kneecap. Ouch. By February of 1945, Serling and his buddies liberated Manila in some of the bitterest urban combat of the war. As the Allied forces pushed the Japanese out block by block, there erupted spontaneous celebrations on the part of the liberated Filipinos. At one of these impromptu street parties, women were dancing in the street as the Japanese began raining down accurate artillery fire. Serling broke cover and ran out into the open to drag a wounded Filipino woman to safety. He took home the Bronze Star for this action.

The commander of the Japanese forces defending Manila was one Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi. He had arrayed 17,000 fanatical Japanese troops across the city amidst a series of well-sited and meticulously-crafted defensive works. By the time Serling and his comrades had finally pulverized the Japanese defenses, the 511th PIR had suffered 50% casualties with more than 400 men killed. During this hard-fought battle, Serling was wounded by an anti-aircraft gun that the Japanese had turned earthward against the assaulting Americans. After a stint in New Guinea to recover, he rejoined his unit in Manila to finish mopping up.

Rod Serling’s final posting was to the Army of Occupation in Japan. During his three years in the military, Serling had not been promoted beyond private. His surly disposition and flighty behavior had hamstrung his leadership prospects. He finished the war as a Technician Fourth Grade (T/4).

Rod Serling’s Rifle

Combat during WW2 was a frenetic, chaotic thing. Many of the vets I have known said they regularly swapped weapons around as operational needs demanded. However, as near as I could tell, most of Rod Serling’s time in combat was spent behind an M1 carbine. Given his primary mission as a demolition specialist, this is not surprising. The handy little carbine was designed for precisely these applications.

We have covered the origin story of the carbine before. Its design was almost an afterthought. A handful of Winchester engineers bodged the little gun together in just thirteen days. The carbine went on to become the most-produced American combat weapon of the war with more than six million copies seeing service.

The carbine has been oft-maligned for its modest stopping power relative to the M1 Garand battle rifle of the day. This really isn’t a fair characterization. The carbine was designed to supplant the M1911A1 handgun, not the service rifle. When compared to a pistol, the carbine was much easier to shoot well and markedly more effective downrange. A good friend who carried one in Italy during the war once told me the carbine was more than adequate to do the job, just that it might take two or three rounds to put a man down.

The Rest of the Story

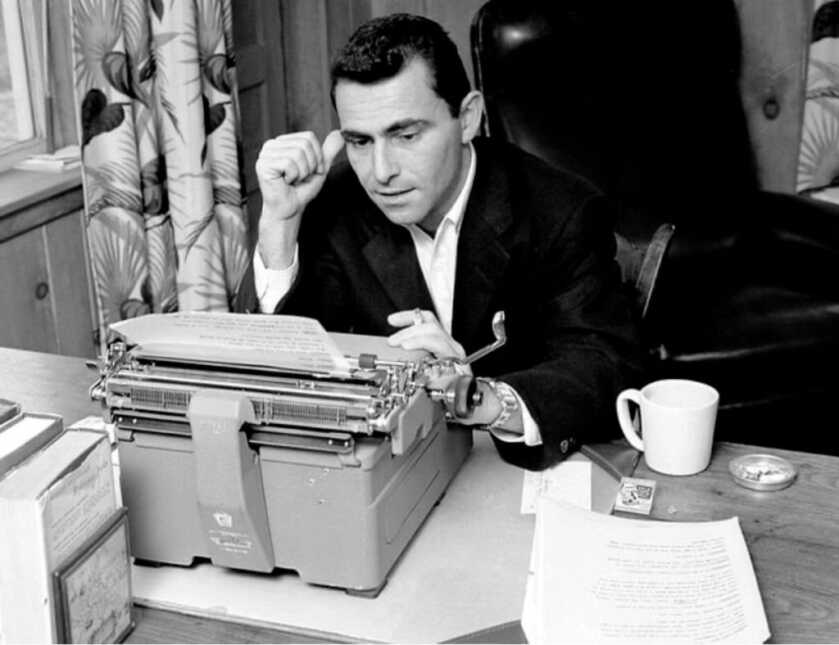

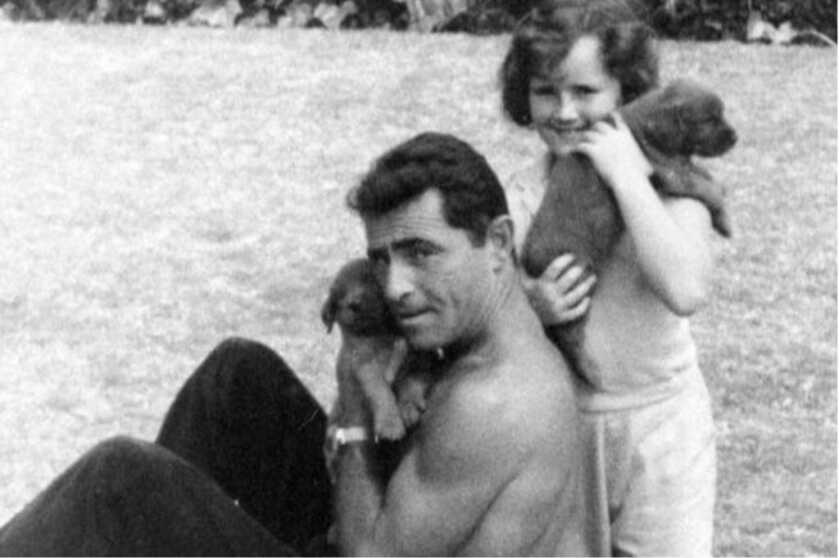

Like most of those great old guys who left home and hearth to travel around the globe to free the world, T/4 Rod Serling returned to the States with some emotional baggage. He had lived unimaginable fear, dispensed death, and lost friends at intimate ranges. In response to all this pain, chaos, and tragedy, he began to write as a sort of catharsis. With this as a basis, he produced some of the most delightfully macabre storylines.

Rod Serling eventually went on to become one of the most well-known figures in television. He worked as a writer, producer, narrator, and playwright. He also taught his craft at Ithaca College in New York and Antioch College in Ohio. I rather suspect his writing classes were just to die for. Throughout it all, Serling used his artistic medium to cope with the stresses he brought home from the war.

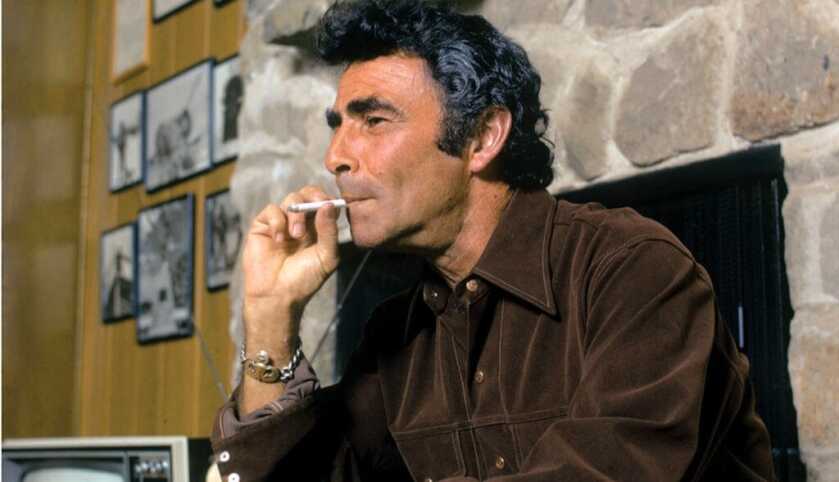

From his earliest years, Rod Serling spoke out on such fulminant social issues as racial equality and censorship in the arts. He was an outspoken opponent of US involvement in Vietnam. Over time he became known as the “Angry Young Man” of Hollywood for his passionate clashes with both sponsors and TV execs.

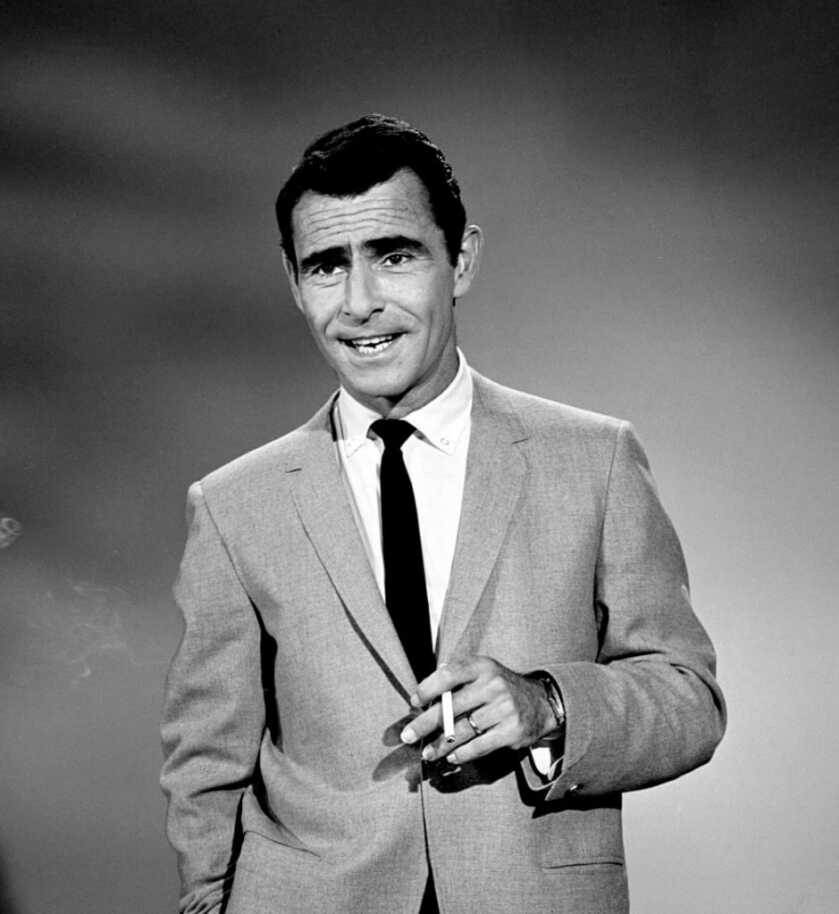

There is no more anxiety-producing human undertaking than combat on the front lines. This unfortunate reality combined with the ready availability of tobacco synergistically brought Serling home from the war with a three to four pack-a-day smoking habit. In early May 1975, the vile weed caught up with him and he had his first heart attack. A second cardiac event two weeks later forced his physicians to recommend an open-heart surgical procedure in an effort to recanalize his coronary arteries. While such stuff is commonplace today, it was still fairly radical back in the 1970’s.

Serling survived the 10-hour operation but suffered a third cardiac blockage while on the table. He died two days later at age 50. One of his most remembered quotes of many was, “For civilization to survive, the human race has to remain civilized.” What an extraordinary guy.

*** Buy and Sell on GunsAmerica! ***

Rod Serling came to Auburn University while I was a student there in the ’70s. He gave a wonderful talk and told about his last visit to Alabama. While he was stationed at Fort Benning, he made the trek across the Chattahoochee River to evil Phenix City, where he got rolled!

One of my fellow students asked Mr. Serling id he could recite the opening to The Twilight Zone. He paused for a second, said it had been many, many years and then reeled it off.

Been watching the New Year’s Twilight Zone marathon on Sci-Fi channel and just so happened to come across this post.

Amazing. I was also at that lecture in Auburn in the early 70s. Being a fan of the show it was quite an opportunity to attend the lecture.

Eric

Something a little off- how many here have had WWII vets as teachers in school? My elementary principal was a WWI vet! I had junior and senior high teachers that fought in WWII, and Korea. My 7th grade history teacher was a hoot. He lost his eyesight when a Japanese Zero shattered the windshield of his plane. His glasses were literally as thick as coke bottles. The stories he told….

We had real men in TV back then. I agree with Dr. Dabbs on about everything because we’re both Southern and have similar backgrounds.

A war hero to boot as bullets couldn’t kill him but cigarettes could. Amazing story. I tried to always watch his show.

AMAZING!

Your writing reminds me in a lot of ways of Paul Harvey’s Rest of the Story. You provide a lot of unknown or little known information.

Thank you

Thank you for sharing.

Whenever I encounter an unexpected complication in my life to overcome, a mental image of Rod Serling, cigarette in hand, uttering the words, “Image if you will” always comes to mind.

How timely… given our most recent history I feel as if we all have entered the “Twilight Zone”.

In Mike Rowe’s book, “The Way I heard It”, he has a chapter on Rod Sterling.

Going sideways, john lithgow did a later color episode of shatner’s Terror, and both referenced it as reality in their respective characters meeting on Third Rock. Many great pointedly aimed episodes as commentary.